Pelvic Fractures

Carrie D. Tibbles and Michael Gibbs

Pelvic fractures are a common and often life-threatening consequence of major trauma. A pelvic fracture suggests a significant force of injury, mandating a careful evaluation for multisystem involvement. Many of these patients are hemodynamically unstable, requiring aggressive volume resuscitation. These patients are at increased risk for associated injuries and significant morbidity and mortality (1). Motor vehicle collisions and automobile–pedestrian trauma are responsible for 60% to 70% of pelvic fractures. Falls from a height account for 10% to 20% of pelvic fractures, and the rest are made up of athletic and direct crush injuries (2). Early resuscitation, accurate fracture classification, stabilization of the pelvis, diagnosis of associated injuries, and coordination of key specialists are the priorities in the emergency department (ED) management of these complex injuries.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

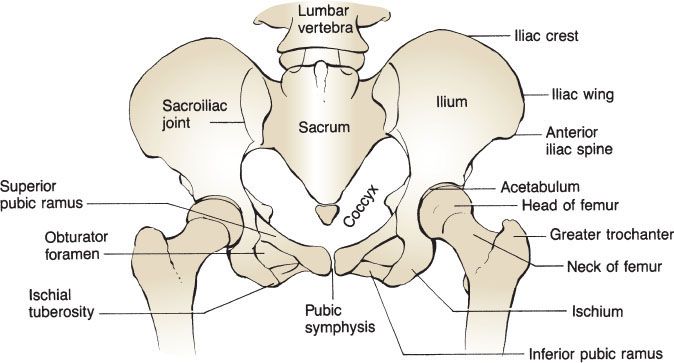

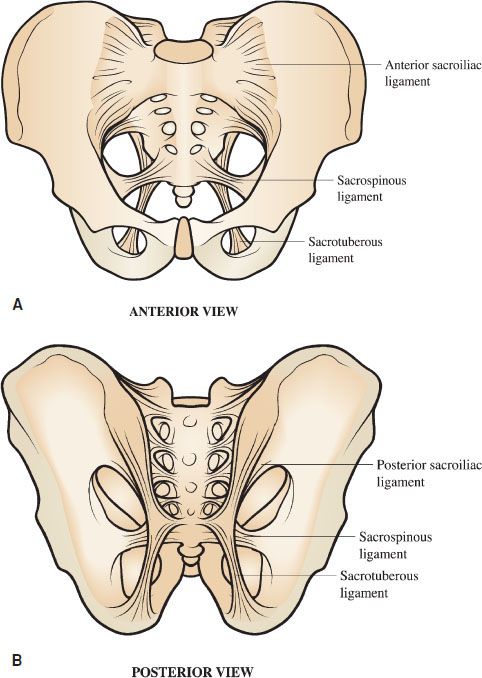

An understanding of both the anatomy of the pelvis and the mechanism of injury is necessary to manage patients with significant pelvic trauma. It is useful to visualize the pelvis as a ring with anterior and posterior components (Fig. 42.1). The posterior pelvic ring, which is critical for stability, is strengthened by several ligaments: the anterior and posterior sacroiliac (SI) ligaments, sacrospinous ligament, and sacrotuberous ligament (Fig. 42.2A,B). Disruption of this powerful ligamentous complex is a marker of tremendous energy transfer. Major blood vessels traversing the posterior pelvic ring are vulnerable when fractures occur here. Anteriorly, the pubic symphysis is the weakest link in the pelvic ring. Disruption of the symphysis alone does not lead to instability, provided the posterior ligamentous structures remain intact. Because the pelvis is a ring structure, if one fracture is identified, there is almost always a second disruption of the ring.

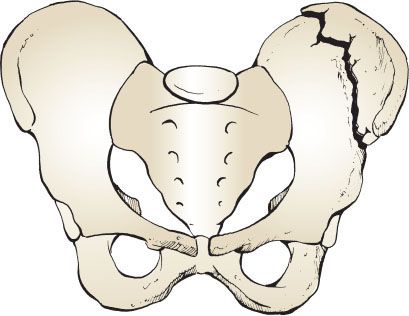

FIGURE 42.1 The pelvis.

FIGURE 42.2 Ligamentous support of the bony pelvis, (A) anterior, and (B) posterior views. The posterior pelvic ring is stabilized by several strong ligaments. Disruption in this region implies major energy transfer and the potential for significant multisystem injury.

Several different pelvic fracture classification systems have been developed. The most widely used system was developed by Young and Burgess and is based on the mechanism of injury (3). Three force vectors are described: lateral compression (LC), anteroposterior (AP) compression, and vertical shear (VS). “Complex patterns” describe injuries that are the result of more than one force vector. Each of these vectors breaks or dislocates the pelvic ring in a predictable pattern and is associated with varying degrees of mechanical instability (Table 42.1) and potential for hemorrhage. Each injury force vector has a unique effect on “pelvic volume”: that is, the potential space created after injury that may accommodate pelvic hemorrhage. Injury vectors that increase pelvic volume (e.g., AP compression, VS) are much more likely to be associated with brisk pelvic bleeding and hemodynamic instability than injury vectors that decrease pelvic volume (e.g., LC).

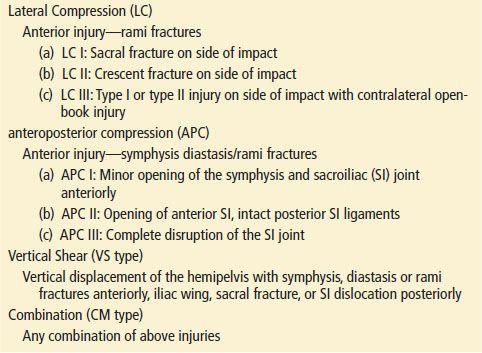

TABLE 42.1

Young–Burgess Classification of Pelvic Fractures

Lateral Compression

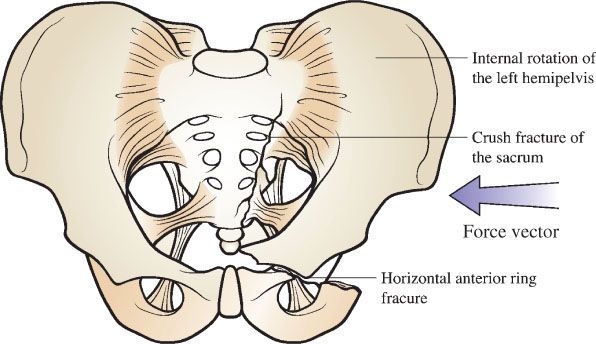

LC fractures account for almost 50% of pelvic fractures. The force is delivered to the pelvis from the side. LC fractures are common after a “T-bone” motor vehicle collision or when a pedestrian is struck from the side. The affected hemipelvis is crushed inward (Fig. 42.3). Stability is usually maintained, and therefore, LC injuries are less likely than other pelvic fractures to have associated major hemorrhage. Morbidity is secondary to coincident blunt force trauma to the head and torso, rather than the pelvic fracture itself.

FIGURE 42.3 Lateral compression injury. The causative force vector is delivered from the side, crushing the affected hemipelvis inward. Lateral compression injuries typically reduce pelvic volume. Instability is variable.

Essential radiographic features of LC fractures include horizontal pubic rami fractures. These fractures are visible 80% of time on the AP view, and this feature alone is highly suggestive of LC injury. Crush fractures of the sacrum are seen in 88% of cases. This fracture may only be visible as a disruption of the arcuate lines. The combination of a crush fracture of the sacrum and a horizontal pubic ramus fracture is diagnostic for a LC injury. Fractures of the acetabulum or hip dislocations can also be seen. SI joint diastasis in combination with any of the other findings also suggests a LC injury.

Another type of fracture that results from LC is the “stove-in” or pelvic wing fracture that was first described by Duverney in 1751 (Fig. 42.4). This fracture may produce an unstable fragment off the iliac crest, but the load-bearing stability of the pelvic ring is not jeopardized.

FIGURE 42.4 Duverney fracture. Pelvic wing or “stove-in” fracture.

Anteroposterior Compression

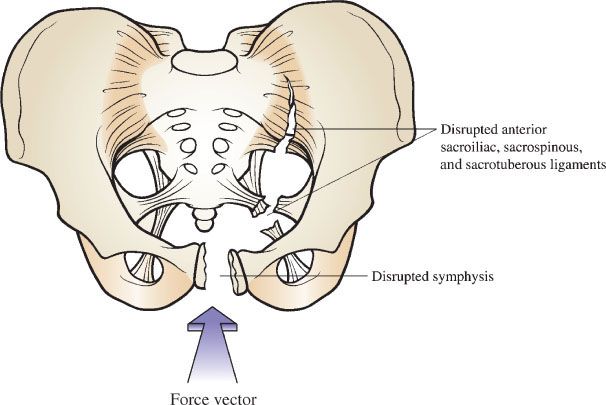

Nearly one-third of pelvic fractures are AP compression injuries. An anterior compressive force causes rupture of the symphyseal ligament and diastasis of the anterior pelvic ring. The posterior ligaments will tolerate up to 2.5 cm of symphyseal diastasis. Progressive widening of the symphysis beyond this point results in disruption of the anterior SI and sacrospinous ligaments. This injury is commonly referred to as an “open-book” pelvic fracture. Severe trauma will disrupt the posterior SI ligaments as well. In these circumstances, the SI joint is shown widely displaced on radiographs.

AP compression fractures are seen following head-on motor vehicle collisions or as a pedestrian is struck head-on by an oncoming vehicle. Forces may also be delivered in a posterior–anterior direction. Both iliac wings are forced outward (Fig. 42.5). AP compression injuries are unstable, and are often associated with brisk pelvic and retroperitoneal hemorrhage. Coincident injuries of the thorax and abdomen are the rule.

FIGURE 42.5 AP compression injury. The causative force vector is delivered from the front (or back), causing the pelvic ring to “open like a book.” These injuries are mechanically unstable, and associated with increases in pelvic volume.

Radiographs of anterior compression injuries will demonstrate vertically oriented pubic rami fractures, symphyseal diastasis, or both, and a variable degree of SI joint disruption. An acetabular fracture is seen in up to one half of patients.

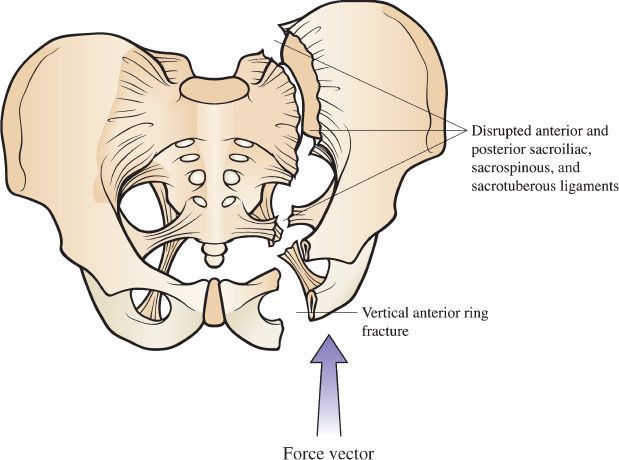

Vertical Shear Fractures

VS injuries occur when a vertically oriented force is delivered to the pelvis via the extended femurs. These rare injuries are usually the result of a fall from a height or follow a head-on motor vehicle collision in which the occupant had the legs fully extended. VS injuries can also result from a downward force delivered to the pelvis via the spine, which may occur when a heavy object falls on the back or shoulders. Because one hemipelvis is driven up (or down) compared to the other (Fig. 42.6), these injuries produce major instability. The hemodynamic consequences are similar to those associated with AP compression injuries. Radiographs of a VS fracture demonstrate severe posterior disruption. This injury appears as either complete SI joint disruption, a vertical sacral fracture, or a medial iliac wing fracture with associated symphyseal disruption or pubic rami fractures.

FIGURE 42.6 Vertical shear injury. The causative force is transmitted up the ipsilateral femur, driving the affected hemipelvis upward. Vertical shear injuries are extremely unstable and associated with increases in pelvic volume.

The Malgaigne fracture, first described in 1859, is characterized by anterior disruption of the pubic symphysis or two to four pubic rami fractures and ipsilateral SI joint disruption. Because of involvement of the posterior arch, these injuries can be complicated by significant neurologic and vascular injury. These patients are often hypotensive, and the mortality rate approaches 20%.

Other Types of Pelvic Fractures

Straddle Injuries

A straddle injury is an unstable injury characterized by bilateral double pubic rami fractures. Classically, this fracture results from falling while straddling a solid object between the legs. Both lateral and AP compressive forces can cause straddle injuries as well. The lower genitourinary tract is particularly susceptible to injury by this mechanism. These injuries are usually closed fractures. Patients will have perineal tenderness, ecchymosis, and gross hematuria. Male patients may be unable to void. The incidence of hemorrhage and bowel injury is high.

Avulsion Fractures

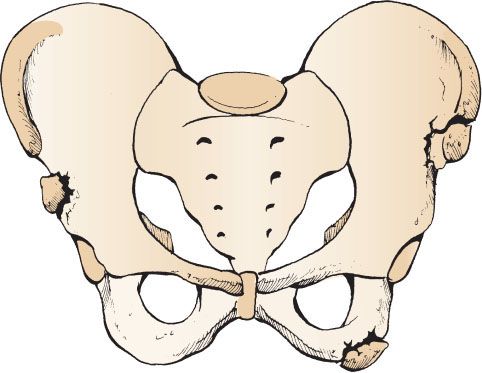

These injuries are among the most trivial of pelvic fractures and are often sustained by athletes who stress the muscular or ligamentous insertions onto the bony pelvis (Fig. 42.7). Avulsions of the anterior superior iliac spine generally occur in adolescent hurdlers and long jumpers. These injuries reflect forceful contraction of the sartorius muscle or abdominal musculature transmitted to the iliac epiphysis. Less commonly, the anterior inferior iliac spine may be avulsed by intense contraction of the straight head of the rectus femoris muscle. This injury may occur in athletes playing sports that involve kicking (e.g., soccer and rugby). Avulsion fractures of the ischial tuberosity are even less common. This injury usually results from strenuous stretching of the pelvic ring, as in hurdling or pole vaulting. Patients with avulsion fractures generally present with a characteristic history and local tenderness. In isolated trauma, there are usually no associated complaints or injuries. These are stable fractures, because the integrity of the pelvic ring remains intact.

FIGURE 42.7 Fractures due to stress on muscular or ligamentous insertions onto the bony pelvis.

Sacral Fractures

Sacral fractures are defined by the orientation of the fracture line and occur in transverse upper, transverse lower, and vertical planes. Upper sacral fractures are frequently difficult to recognize both radiographically and clinically. These fractures often present only as buttock and perianal pain. These fractures may injure sacral nerve roots resulting in decreased anal sphincter tone and loss of perineal sensation. Lower sacral fractures are equally painful but are rarely complicated by neurologic injury. A careful physical examination to exclude rectal tears is important. Vertical sacral fractures occur as a result of VS injury.

Patients who fall from a standing height frequently present with pelvic pain localized to the bony prominences. Areas such as the iliac spine, ischial tuberosities, superior pubic rami, and coccyx are particularly susceptible to direct trauma. These fractures are stable injuries and are particularly common in elderly osteopenic patients. Presentation involves localized pain, swelling, and ecchymosis. There are usually no associated injuries.

Associated Injuries

Significant force is required to disrupt the pelvic ring. Consequently, associated injuries, both to adjacent viscera as well as organs distant to the pelvis, are common following major pelvic trauma. The Injury Severity Score, as a surrogate marker of organ injury, is an important predictor of mortality in patients with pelvic fractures (4).

Approximately one-fourth of pelvic fractures are complicated by injuries to the urethra or bladder (5). More than 95% of patients with an injury to the posterior urethra and 70% to 95% of patients with a bladder injury following blunt trauma have a pelvic fracture. Bladder injury is usually the result of perforation by fracture fragments and is found in patients with symphyseal diastasis and those with multiple pubic rami fractures. The posterior urethra is also prone to injury following anterior pelvic fractures because it is firmly attached to the pubis by the puboprostatic ligament.

Upper sacral fractures, VS fractures, fractures of the sciatic notch, and SI joint injuries are frequently complicated by injuries to the lumbosacral plexus. The overall incidence of neurologic injury in patients with pelvic fractures is reported to be 10% to 21%. The incidence of neurologic injury is as high as 50% in fractures with posterior disruption (4). Such patients may present with distal motor weakness (impaired dorsiflexion or plantar flexion of the great toe), numbness on the dorsal and lateral aspect of the foot, a diminished Achilles tendon reflex, or evidence of cauda equina syndrome, including perianal anesthesia and loss of sphincter tone.

Open pelvic fractures are defined as a fracture with direct communication with a vaginal, rectal, or skin wound. These fractures are invariably associated with severe injuries of the pelvic viscera. Early mortality is attributed to severe blood loss or associated chest or intracranial injuries. Historically, mortality may be as high as 30% to 50% (6). Following the initial resuscitation phase, heavy contamination of perineal wounds resulting from damage of the rectum and genitourinary tract increases the risk of delayed complications, including abscess formation, sepsis, and multiorgan failure.

ED EVALUATION

Physical Examination

During the initial resuscitation of the severely injured trauma patient, the priorities are to rapidly identify immediate life-threatening injuries and to initiate resuscitation. In the patient with a pelvic fracture, hypotension is an ominous sign, and a search for the cause should be rapidly initiated.

The objectives of the physical examination of the pelvis are to estimate the likelihood of a pelvic fracture and to identify any complications and associated injuries. The physician should inspect and palpate the front and back of the pelvis noting any abrasions, contusions, lacerations, tenderness, or crepitus. Although the identification of an unstable pelvic ring is important, overzealous rocking of the disrupted pelvis may cause additional retroperitoneal bleeding. It is preferable to apply gentle steady downward and lateral pressure on the iliac wings to detect or exclude tenderness. If tenderness is present, appropriate imaging should follow. In the obtunded blunt trauma patient with a possible pelvis injury, imaging should be performed.

Signs of urethral injury include blood at the urethral meatus, penile or scrotal hematoma, and a high-riding prostate. Patients with these findings should have a retrograde urethrogram before insertion of a Foley catheter to avoid worsening of an incomplete urethral tear. A careful vaginal examination should be performed in female patients. Perineal lacerations may have associated intravaginal mucosal tears. Bleeding is the hallmark of vaginal trauma, although it may not be immediately apparent because of muscle spasm. Vaginal injury should also be suspected if hematuria is present, or it is difficult to pass a Foley catheter.

The lumbosacral plexus is prone to injury in pelvic fractures, and a neurologic examination of the lower extremity should be performed with particular attention to the L5 and S1 nerve roots. In the patient who is awake, motor function of the L5 nerve root is assessed by dorsiflexion of the great toe against resistance. The S1 nerve root is tested by having the patient plantar flex the great toe. L5 supplies sensation to the dorsum of the foot, and S1 supplies sensation to the lateral aspect of the foot. The Achilles tendon reflex, perianal sensation, and sphincter tone should also be assessed.

Indications for Pelvic Imaging

The severely injured blunt trauma patient who is either hemodynamically unstable or obtunded or who has clinical evidence of lower abdominal or pelvic injury requires pelvic imaging. For less severely injured patients, a thorough physical examination can be used to identify the patient at low risk for pelvic fracture who can be managed safely without imaging. In a prospective trial of 2,176 alert blunt trauma patients, Gonzalez et al. (7) demonstrated that the physical examination was 93% sensitive for detecting pelvic fractures and 100% sensitive for detecting those requiring operative repair. Pelvic imaging in blunt trauma patients is recommended for patients who:

1. Are clinically unstable.

2. Have lower abdominal or pelvic tenderness.

3. Have other signs of pelvic trauma (perineal hematoma, blood at the urethral meatus, gross hematuria).

Pelvic x-Rays

A single AP radiograph will identify the large majority of pelvic fractures and can provide sufficient information to guide early management. The AP radiograph provides specific clues that will help identify the various injury patterns and fractures described in the previous section (Figs. 42.8–42.12). The film should visualize the iliac crests, each hip joint, the fifth lumbar vertebrae, and the proximal portion of each femur. Important landmarks include the pubic symphysis, superior and inferior rami, anterior superior and anterior inferior iliac spines, SI joints, sacral ala, sacral foramen, and L5 transverse processes.

FIGURE 42.8 AP plain film of a severe lateral compression injury. The left hemipelvis is crushed inward.