SCROTUM

Scrotal pain is one of the most common urologic emergencies seen in boys. Although many causes of scrotal pain may not require an immediate organ-preserving procedure, some causes can lead to rapid and permanent loss of testicular function without timely intervention. Thus, the clinician must identify patients who need emergent diagnostic and/or therapeutic procedures and those who need observation and reassurance.

Consider testicular torsion in males with acute scrotal pain, because torsion is a urologic emergency. The estimated incidence of torsion in U.S. males younger than 18 years is 3.8 per 100,000 children.1 Testicular torsion has a bimodal age presentation, with one peak in the immediate neonatal period and another peak during early puberty. Because the testicle of neonates with prenatal torsion is not salvageable, many urologists agree that neonates can be taken to the operating room on a semi-elective basis when the infant is a few months of age to decrease the anesthesia risk. However, in perinatal torsion, the contralateral side may also be torsed, even without abnormal physical examination findings or an abnormal US.2

Most boys with testicular torsion present between 12 and 18 years of age. Classically, the pain is abrupt in onset and severe and is usually associated with nausea or vomiting. The testicle is extremely painful, and often the patient will walk with a wide-based gait to minimize the contact of the scrotum to the thigh. There may be a preceding history of a sports activity or even minor trauma to the area, which may lead the clinician to a misdiagnosis of traumatic injury. In some cases, the patient may recall episodes of previous scrotal pain that rapidly resolved without intervention, which may represent intermittent torsion with spontaneous detorsion. Episodes of intermittent torsion may predispose a patient to acute complete testicular torsion.3

Classic physical examination findings of acute testicular torsion include a swollen, tender, high-riding testis, with an abnormal transverse lie. There are often scrotal skin changes. Ipsilateral loss of the cremaster reflex is almost always noted but is not 100% sensitive, especially in young boys.4,5

Doppler US is the diagnostic imaging study of choice,6 with radionuclide imaging a distant second. If the time to obtain diagnostic imaging may lead to delay of surgical intervention, advocate for emergent surgical exploration by a urologist, rather than waiting for an imaging study to be completed. Time is especially critical if the duration of symptoms is <6 hours, as the salvage rate is excellent in such cases. Beyond 6 hours, the salvage rate becomes progressively worse, and after 48 hours of symptoms, the salvage rate is near zero. Patients presenting with equivocal signs of torsion or who have had pain for >6 hours may benefit from a Doppler US, which can visualize blood flow to the testis. In acute torsion, Doppler demonstrates an enlarged testis with decreased or absent flow compared with the unaffected side. In patients with suspected intermittent torsion who have a normal Doppler US and resolution of pain, counsel the patient and family to seek medical attention immediately should the pain recur, and recommend urologic follow-up as an outpatient.

Manual detorsion may be indicated for patients with torsion when there is no urologist immediately available and when the duration of symptoms is too long for surgical salvage. Administer parenteral opioid analgesia, local anesthesia (infiltrating the spermatic cord near the external ring with lidocaine), or procedural sedation. Because the testis tends to torse in the medial direction, manual detorsion is accomplished by holding the testis between the thumb and index finger and rotating the testis in an outward direction toward the thigh (as if opening a book). However, the spermatic cord may be twisted >180 degrees, making it difficult to recognize how many times the testis should be outwardly rotated. Also, a very swollen hemiscrotum may make isolating the testis between two fingers challenging. The unsedated, older, verbal patient may be able to describe relatively immediate relief upon successful detorsion. Bedside or formal Doppler US may be useful in determining improvement of flow. The success rate of manual detorsion is quite variable and is not definitive therapy. Even after manual detorsion, patients need emergent surgical exploration to confirm complete detorsion and to perform bilateral orchidopexy.

The appendix testis and appendix epididymis are testicular embryologic remnants that can twist, resulting in venous congestion and subsequent infarction of the appendage. Torsion of a testicular appendage is most common in males between 7 and 12 years of age, although it can occur at any age. Typically, the patient’s symptoms are more insidious than true testicular torsion, with less severe pain and lack of systemic symptoms. Early in the course before scrotal edema and erythema develop, it may be possible to localize the point of tenderness to the upper pole of the testis or epididymis. In addition, one may observe the infarcted appendage through the scrotal skin (“blue dot sign“). If Doppler US is obtained, there should be normal testicular flow with a small hyperechoic region adjacent to the testis. Management consists of scrotal support, limitation of activity, and oral analgesics (e.g., nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs). If torsion of the testicular appendage is diagnosed early in its course, the pain may worsen before ultimate improvement due to ongoing inflammation, and this is an important point of counseling to prevent return to the ED.

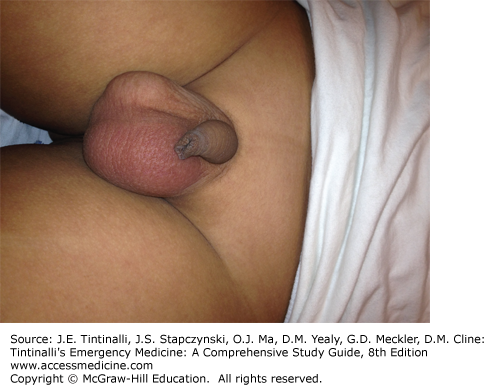

Epididymitis, or inflammation of the epididymis, is a common cause of scrotal pain in pre- and postpubertal boys that does not require surgical intervention. In a 2014 study of 252 patients with epididymitis presenting to an outpatient pediatric urology referral practice, the mean age at first presentation was 10.92 years, with the majority of cases occurring between 10 and 14 years.7 In sexually active males, acute epididymitis may result from ascending urethral infection due to Chlamydia trachomatis or Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Epididymitis may also result from enterovirus or adenovirus infection.8 Symptoms are insidious in onset, with dysuria, frequency, or fever. Prehn’s sign (relief of pain by elevating the scrotum) is not consistently reproducible in boys. Typically, the affected testis is mildly enlarged and tender with hemiscrotal erythema and swelling (Figure 133-1). Urinalysis may demonstrate pyuria and bacteriuria. Obtain urine culture and sensitivity, and in suspected sexual transmission, obtain urethral cultures for C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae and treat with empiric antibiotics pending culture results.

Doppler US, if the diagnosis is in doubt, shows an enlarged epididymis with increased blood flow, and normal blood flow to the testis. It is often difficult to differentiate torsion of a testicular appendage from epididymitis by US, but neither disorder requires surgical intervention. Treatment of epididymitis is somewhat controversial, with some advocating analgesics and limited activity only and others supporting treatment with antibiotics, even in the non–sexually active male.

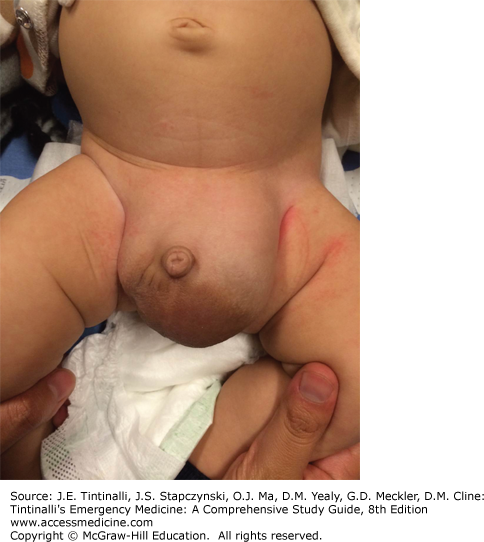

Hydrocele (Figure 133-2), the accumulation of fluid around the testis, is the most common cause of painless scrotal swelling in children. Parents often note intermittent swelling of one or both sides of the scrotum. This painless swelling may resolve when supine or sleeping and become more prominent when awake or crying. Hydrocele is termed noncommunicating if there is residual but static swelling after the processus vaginalis has closed, or communicating if swelling increases and decreases through a patent processus vaginalis. The diagnosis is confirmed by transillumination, whereby an otoscope or other light source is placed on the affected hemiscrotum and the hydrocele fluid is illuminated like a lantern; by contrast, a thickened scrotal wall or pure testicular enlargement will not transilluminate.

Most simple hydroceles resorb by 18 to 24 months of age. A communicating hydrocele is often associated with inguinal hernia, and as long as the hernia is reducible, it does not require emergent surgical repair. Management of most hydroceles includes outpatient scrotal US with referral to urology.

Varicocele is another cause of painless scrotal swelling and typically presents at the onset of puberty. It is due to abnormal dilation of spermatic cord veins, also known as the pampiniform plexus, due to faulty valvular venous return. Most varicoceles occur on the left, possibly due in part to the acute angle of confluence with the left renal vein and resulting higher venous pressure. Classically the mass of enlarged veins can be palpated superior and posterior to the testis (“bag of worms”) and is more prominent when standing or with the Valsalva maneuver; even large varicoceles may be missed in the supine position. Varicoceles are managed on an outpatient basis by urology. The implications of possible subfertility should be discussed in the urologist’s office.

Intrascrotal tumors are uncommon in young children; however, testicular tumors are the most common solid tumor among adolescent males.9 The testicular or paratesticular tumor usually presents as a painless, firm, unilateral scrotal mass. Evaluation includes serum α-fetoprotein and tumor β-human chorionic gonadotropin levels, scrotal US, and urgent urologic consultation.

DISORDERS OF THE PENIS

A swollen, red, or painful penis can usually be categorized as a disorder of the foreskin or of the shaft of the penis. The most common abnormalities of the foreskin are phimosis, paraphimosis, and balanoposthitis. Penile shaft disorders occur less commonly and include priapism, tourniquet syndrome, and zipper injury.

Phimosis is caused by stenosis of the distal aspect of the foreskin, preventing retraction of the foreskin over the glans. There may be a history of ballooning of the foreskin during urination, with dribbling of entrapped urine after voiding is complete (Figure 133-3). Most uncircumcised infants have normal, physiologic phimosis. Nearly all cases of physiologic phimosis spontaneously resolve by 5 years of age and rarely require treatment other than daily cleaning while bathing. If a patient has persistent phimosis beyond school age and the parent desires treatment, topical steroid cream can be effective.10,11 Acquired cases of phimosis may be secondary to recurrent balanoposthitis, poor hygiene, or forcible retraction of the foreskin. Acquired cases are often refractory to medical management and may ultimately require circumcision. One of the few true emergencies related to phimosis occurs when the foreskin is nearly completely sealed off, causing acute urinary retention. Such cases may require dilation of the foreskin under procedural sedation or dorsal penile block to place a Foley catheter.

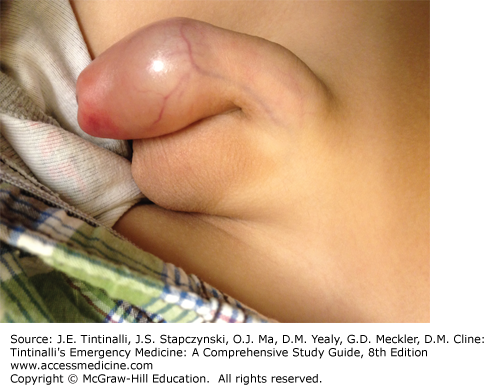

Paraphimosis is a true urologic emergency. This occurs when a tight ring of phimotic foreskin is retracted proximal to the glans and becomes trapped in that position. Subsequent impairment of venous and lymphatic drainage causes progressive swelling of the glans and foreskin. If the paraphimosis is not promptly reduced, arterial blood supply becomes compromised, and the glans may necrose.

Symptoms of paraphimosis are pain, erythema, and swelling of the shaft and glans, distal to the constricting ring of foreskin (Figure 133-4). The area of the shaft proximal to the constriction appears normal. Because delay in reduction will lead to worsening edema resulting in a more difficult manual reduction, paraphimosis should be reduced as soon as possible. Mild paraphimosis may be manually reduced without the need for sedation or analgesia. More difficult cases will require either a dorsal penile nerve block or procedural sedation, depending on the age and degree of cooperativeness of the patient.