The development of pediatric intensive care services should take account of the level of preventive and basic curative treatment that are available to all children in that country, and the national and subnational mortality rates. It should also be based on an understanding of disease epidemiology in that country or region.

The development of pediatric intensive care services should take account of the level of preventive and basic curative treatment that are available to all children in that country, and the national and subnational mortality rates. It should also be based on an understanding of disease epidemiology in that country or region. Dramatic reductions in child mortality and overall improvements in child health have occurred in high-income and many transitional economies, but within many developing countries, inequity in child health outcomes remains vast. The causes of inequity are poverty and its consequences, such as low education, poor access to quality health services, and inadequate attention to human rights.

Dramatic reductions in child mortality and overall improvements in child health have occurred in high-income and many transitional economies, but within many developing countries, inequity in child health outcomes remains vast. The causes of inequity are poverty and its consequences, such as low education, poor access to quality health services, and inadequate attention to human rights. Pneumonia, diarrhea, malaria, and injuries are consistently the leading causes of deaths in children outside the neonatal period, and preterm complications, birth asphyxia and neonatal sepsis, are consistently the commonest causes of neonatal deaths. Worldwide, the rates for some diseases are falling dramatically because of better disease control programs.

Pneumonia, diarrhea, malaria, and injuries are consistently the leading causes of deaths in children outside the neonatal period, and preterm complications, birth asphyxia and neonatal sepsis, are consistently the commonest causes of neonatal deaths. Worldwide, the rates for some diseases are falling dramatically because of better disease control programs. Most of the care of seriously ill children in the least-developed countries is provided by nurses, paramedical workers, and nonspecialist doctors in rural or remote hospitals or overcrowded urban hospitals.

Most of the care of seriously ill children in the least-developed countries is provided by nurses, paramedical workers, and nonspecialist doctors in rural or remote hospitals or overcrowded urban hospitals. In developing and transitional countries, pediatric intensive care specialists have the potential to improve the management of seriously ill children throughout their country, by providing training for staff in smaller hospitals and by encouraging the building of effective emergency health systems for children.

In developing and transitional countries, pediatric intensive care specialists have the potential to improve the management of seriously ill children throughout their country, by providing training for staff in smaller hospitals and by encouraging the building of effective emergency health systems for children. In the countries with limited resources, the provision of publicly funded intensive care that will benefit only a few has to be weighed against the greater needs of many.

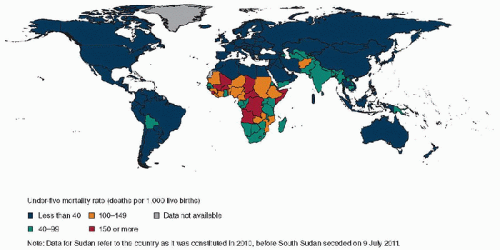

In the countries with limited resources, the provision of publicly funded intensive care that will benefit only a few has to be weighed against the greater needs of many. Outside North America, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand, there are over 60 countries that have under-5 mortality rates <30 per 1000 live births, where intensive care services are likely to have a substantial impact on child survival at a population level.

Outside North America, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand, there are over 60 countries that have under-5 mortality rates <30 per 1000 live births, where intensive care services are likely to have a substantial impact on child survival at a population level. Innovations in intensive care in developing countries should focus on simpler, safer, and cheaper technology, and this has the potential to influence the way intensive care is practiced worldwide.

Innovations in intensive care in developing countries should focus on simpler, safer, and cheaper technology, and this has the potential to influence the way intensive care is practiced worldwide.challenge. Even in many transitional economies, access to intensive care is so expensive that it is only for the richer classes and can drive less wealthy families into poverty. Most of the care of seriously ill children in the least-developed countries is provided by nurses, paramedical workers, and nonspecialist doctors in rural or remote hospitals or overcrowded urban hospitals. In most such hospitals, resources are inadequate, there is poor access to evidence and information, and there is little ongoing professional development or staff training (5,6). These basic deficiencies affect the lives of millions of children each year and are the background to any consideration of the appropriate role of intensive care.

globally are listed in Table 1.1 (7). Pneumonia, diarrhea, malaria, and injuries are consistently the leading causes of deaths in children outside the neonatal period, and preterm complications, birth asphyxia and neonatal sepsis, are consistently the commonest causes of neonatal deaths. The proportions are region-specific, with skewed distribution in the Africa region. For example, 94% and 89% of the world’s malaria and HIV/AIDS deaths occur in Africa. Worldwide, the rates for some diseases are falling dramatically because of better disease control programs. For example, there has been a comprehensive approach to malaria control, including a change to artemisinin-based drug treatment, rapid diagnostic tests, indoor residual insecticide spraying, and research into malaria vaccines. However, the largest impact on malaria morbidity and mortality has occurred from widespread distribution of insecticide-treated mosquito nets. Malaria cases are falling in at least 25 endemic countries in 5 WHO regions. In 22 of these countries, the number of reported cases fell by 50% or more between 2000 and 2006-2007.

globally are listed in Table 1.1 (7). Pneumonia, diarrhea, malaria, and injuries are consistently the leading causes of deaths in children outside the neonatal period, and preterm complications, birth asphyxia and neonatal sepsis, are consistently the commonest causes of neonatal deaths. The proportions are region-specific, with skewed distribution in the Africa region. For example, 94% and 89% of the world’s malaria and HIV/AIDS deaths occur in Africa. Worldwide, the rates for some diseases are falling dramatically because of better disease control programs. For example, there has been a comprehensive approach to malaria control, including a change to artemisinin-based drug treatment, rapid diagnostic tests, indoor residual insecticide spraying, and research into malaria vaccines. However, the largest impact on malaria morbidity and mortality has occurred from widespread distribution of insecticide-treated mosquito nets. Malaria cases are falling in at least 25 endemic countries in 5 WHO regions. In 22 of these countries, the number of reported cases fell by 50% or more between 2000 and 2006-2007. have moderate or severe malnutrition, and malnutrition is implicated in deaths from diarrhea (61%), malaria (57%), pneumonia (52%), and measles (45%). Nearly three-fourths of the world’s malnourished children live in 10 countries, and >99% live in developing countries. While children often present with a single condition (e.g., acute respiratory infection), those who are most likely to die will often have experienced several other infections in recent months, have more than one infection currently (e.g., pneumonia and diarrhea, or pneumonia and malaria), and have malnutrition with micronutrient (such as iron, zinc, or vitamin A) deficiency (Fig. 1.2). In the first decade of this century, child death rates continued to decline such that >2 million fewer children died in 2011 than in 2000. (4)

have moderate or severe malnutrition, and malnutrition is implicated in deaths from diarrhea (61%), malaria (57%), pneumonia (52%), and measles (45%). Nearly three-fourths of the world’s malnourished children live in 10 countries, and >99% live in developing countries. While children often present with a single condition (e.g., acute respiratory infection), those who are most likely to die will often have experienced several other infections in recent months, have more than one infection currently (e.g., pneumonia and diarrhea, or pneumonia and malaria), and have malnutrition with micronutrient (such as iron, zinc, or vitamin A) deficiency (Fig. 1.2). In the first decade of this century, child death rates continued to decline such that >2 million fewer children died in 2011 than in 2000. (4)in low-income countries. Some interventions protect against deaths from many causes, for example, breast-feeding protects against deaths from diarrhea, pneumonia, and neonatal sepsis; insecticide-treated materials (bed nets, sheets, etc.) protect against deaths from malaria and anemia and also reduce deaths from preterm delivery. However, with the exception of breast-feeding (estimated global coverage of 90%), global coverage of basic interventions for reducing child deaths from common conditions is low. The WHO/UNICEF Child Survival Strategy aims for the universal implementation of a basic package of interventions, along with advocacy for better health financing, and a better political environment for child survival. The United Nations Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) contain benchmarks and targets for countries in reducing child mortality rates, with most countries aiming for a two-thirds reduction in under-5 mortality from the national figure in 1990, by 2015 (9). That time is fast approaching, and now there is a need to see beyond 2015 and set targets beyond the MDGs.

TABLE 1.1 THE MAJOR CAUSES OF DEATHS IN CHILDREN UNDER 5 YEARS OF AGE GLOBALLY, WITH ESTIMATES FOR 2000-2003 AND 2010 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree