Chapter 52 Pediatric Considerations in Emergency Nursing

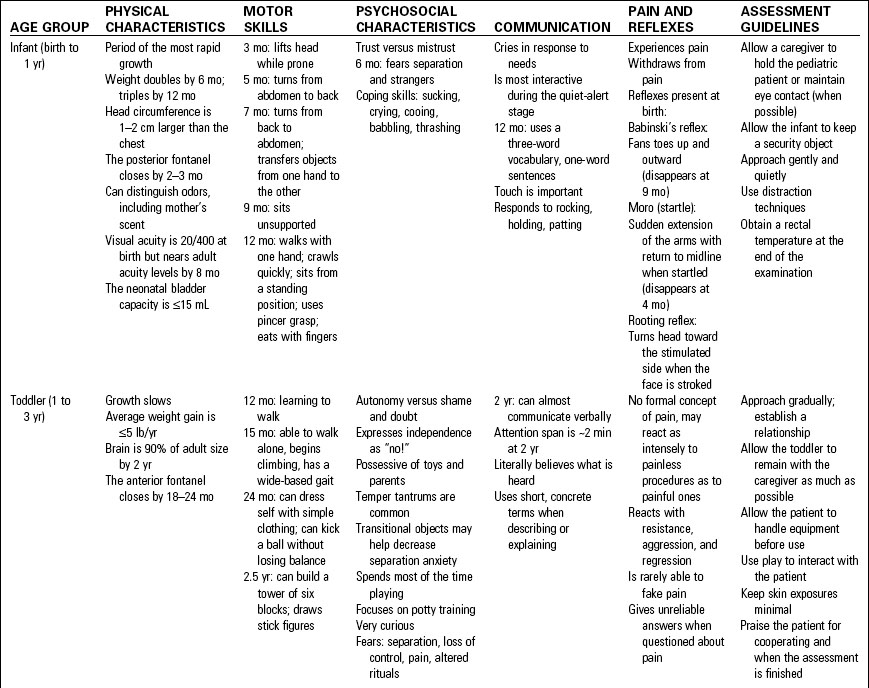

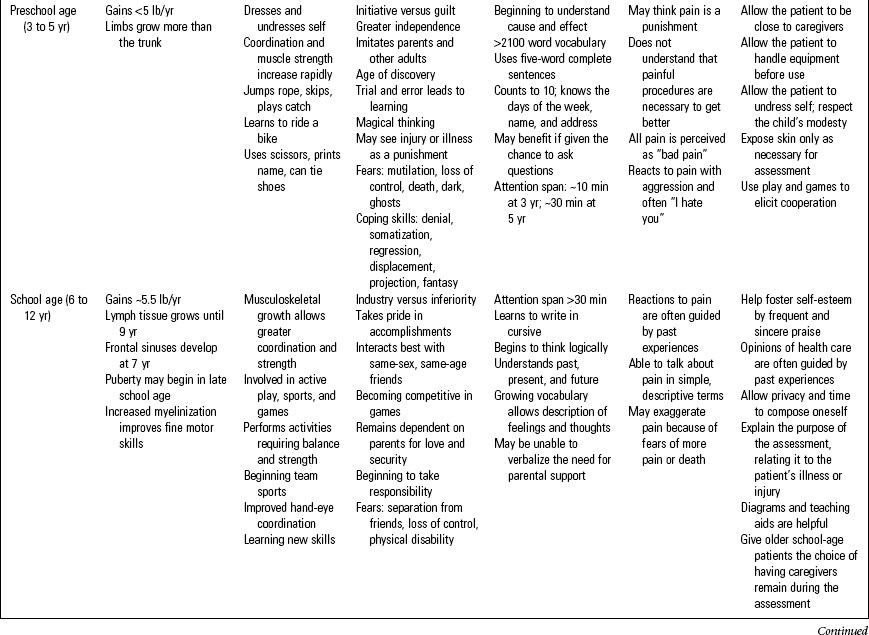

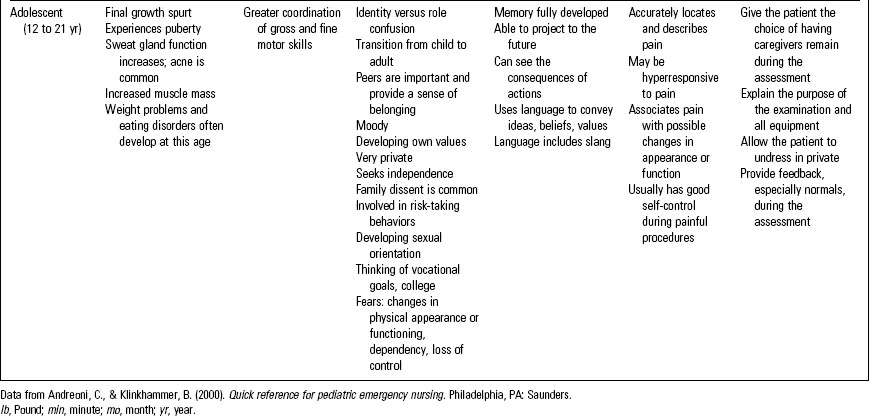

Pediatric patients present a unique challenge to the emergency nurse because of the physiologic and anatomic differences and the vast growth and developmental characteristics specific to this population. Table 52-1 provides information about physical and psychosocial characteristics of the growing child along with guidelines for nursing assessment.1 In addition, keep in mind that family plays an important role in a child’s health care experience.

Pediatric Triage (Prioritization of Care)

Pediatric Assessment Triangle

The PAT is a simple observational tool for performing a rapid, visual, across-the-room assessment of children presenting to the emergency department (ED) regardless of presenting complaint.2 The PAT consists of the following three components:

• Appearance: Muscle tone, consolability, spontaneous movements, speech or cry, distress level

• Breathing: Respiratory distress, abnormal airway sounds

• Circulation: Skin color, such as pale, mottled, cyanotic, or flushed

• Patient’s developmental stage: Is this current behavior in line with his or her typical behavior?

• Significant developmental delays

• Illnesses and injuries common to different developmental ages

• Risk factors for maltreatment

• Compensatory mechanisms of pediatric patients that may mask serious illness or injury

The rationale for additional history may include the following:

• Caregiver concerns and perceptions: crying and “fussiness” are vague symptoms

• Rashes that may be a concern for potentially contagious diseases

• Delay in definitive care and nonuse of emergency medical services because of the portability of children

• Use of cultural and home treatments prior to arrival at the ED

• Lack of primary care provider or lack of preventive care (immunization status)

Focused Assessment and History

Following the rapid visual across-the-room assessment, the next step in triage is the focused assessment, which includes the primary and secondary assessments. Refer to Chapter 44, Pediatric Trauma, for more information. Systematically obtain a history, which can be done by using the pneumonic CIAMPEDS (Table 52-2).

ED, Emergency department.

Reprinted from Emergency Nurses Association. (in press). Emergency nursing pediatric course (4th ed.). Des Plaines, IL: Author.

Vital Signs

For pediatric patients, obtain a full set of vital signs, including weight in kilograms; obtain a measured weight whenever possible. If circumstances do not permit a measured weight using a scale or length-base resuscitation tape, the weight may be estimated using the following formula: Weight in kilograms = (3 × Age) +7.3 The nurse should be aware of the normal vital signs for a pediatric patient and recognize when vital signs deviate from normal. Normal heart and respiratory rates are described in Table 52-3.

TABLE 52-3 NORMAL RESPIRATORY AND HEART RATES BY AGE GROUP

| AGE GROUP | NORMAL RESPIRATORY RATE, BREATHS PER MINUTE | NORMAL HEART RATE, BEATS PER MINUTE |

|---|---|---|

| Infant (1 to 12 months) | 30–60 | 100–160 |

| Toddler (1 to 3 years) | 24–40 | 90–150 |

| Preschooler (3 to 5 years) | 22–34 | 80–140 |

| School-aged child (5 to 11 years) | 18–30 | 70–120 |

| Adolescent (11 to 18 years) | 12–16 | 60–100 |

Reprinted from Emergency Nurses Association. (in press). Emergency nursing pediatric course (4th ed.). Des Plaines, IL: Author.

Temperature

• Obtain temperature via an appropriate route considering the pediatric patient’s age and condition.

• Avoid rectal temperatures in immunocompromised patients.

• Fever can be associated with abnormal activity, respiratory patterns, or dermal warning signs, such as rashes, cyanosis, or mottling.

• Temperature variations that may indicate a serious condition include the following:

Medication Administration and Intravenous Therapy

Because virtually all pediatric medications are dosed according to the pediatric patient’s weight, obtain an accurate measurement as part of the focused assessment. If this is not possible, use a length-based resuscitation tape to calculate estimated body mass or use the formula described above. Pediatric patients present unique risk factors that can contribute to medication errors; therefore reducing or managing these risk factors is important. The age and developmental stage of the pediatric patient are essential to consider whenever administering medications. Not only will age influence drug absorption, distribution, and excretion, but the patient’s age will often determine the best route for administration and appropriate developmental approaches.5

Oral Medications

• Ask the caregiver how the patient usually takes oral medication.5

• Mix or dilute medications in a minimal amount of fluid, applesauce, or chocolate syrup to encourage the patient to ingest the entire dose. When mixing medication with food or liquids use as little diluent as possible.5

• Demonstrate to caregiver how to use a syringe to administer medications in the young pediatric patient’s buccal cavity.

• Administer oral medication while the pediatric patient’s head is raised or while the patient is in a sitting position to prevent asphyxiation.5

• Consult the pharmacist before opening capsules for administration.5

Intramuscular Medications

When determining an injection site, consider the pediatric patient’s age, weight, and muscle mass, along with the medication volume and viscosity. Table 52-4 provides information regarding intramuscular injections in children.

TABLE 52-4 PEDIATRIC INTRAMUSCULAR INJECTION SITES

| SITE | RECOMMENDED AGE |

| Vastus lateralis | Infant |

| Can be used at any age and is the preferred site in children younger than 3 years | |

| Considerations | |

| Large muscle mass, free of important nerves and blood vessels | |

| Acceptable injection volumes: Infants, 0.5–1 mL; older children, up to 2 mL | |

Use a 22- to 25-gauge needle (length,  to 1 inch) to 1 inch) | |

| SITE | RECOMMENDED AGE |

| Ventrogluteal | Child |

| Consider for children older than 3 years | |

| Considerations | |

| Large muscle mass, free of important nerves and blood vessels | |

| Easily accessible site | |

| Injection volume up to 2 mL | |

| Use a 20- to 25-gauge needle (length, 1 to 1.5 inch) | |

| SITE | RECOMMENDED AGE |

| Deltoid | Infant |

| Considerations | |

| Small muscle mass, easily accessible, with a rapid absorption rate | |

| Danger of radial nerve injury in young children | |

| Injection volumes of 0.5–1 mL | |

Use a 22- to 25-gauge needle (length,  to 1 inch) to 1 inch) |

Data from Bindler, R., & Howry, L. (2005). Pediatric drug guide. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

Subcutaneous Injections

• Sites considered include the upper lateral arm, the anterior thigh, and the anterior abdominal wall.5

• Limit the injection volume to 0.5 to 1 mL, depending on the age of the patient and the site of the injection.5

• Insert needle at a 45- to 60-degree angle in a thin pediatric patient with little subcutaneous tissue or at a 90-degree angle in the patient with generous amounts of subcutaneous fat.5

Intravenous Therapy

Establishing and maintaining vascular access in the young pediatric patient is one of the most difficult and stressful emergency nursing tasks. Tips for successful intravenous (IV) therapy include the following6:

• Provide emotional support to patients and their caregivers; this procedure is anxiety-provoking for both. Give caregivers permission to stay with the patient or leave the room during the procedure.

• Infants tend to have deep veins that are well covered with subcutaneous tissue. In these patients, scalp veins are an excellent alternative to extremity sites.

• In the presence of volume depletion, younger pediatric patients may have no visible peripheral veins, even after a tourniquet has been applied.

• Quickly consider an intraosseous site if the patient is critically ill or injured and requires emergent vascular access. Intraosseous lines offer many benefits and few drawbacks. Refer to Chapter 10, Intravenous Therapy, for more information.

• When selecting a site, try to avoid the antecubital fossa, veins over joints, or the dominant hand.

• Use a warm pack (consider use of a commercially available heel warmer) to dilate potential veins.

• Immobilize the pediatric patient’s extremity before venipuncture if possible. A padded pediatric armboard works well.

• Insert the IV device into the skin at an angle, generally 10 degrees, although this may vary. Flush the catheter with a small amount of saline to ensure patency.

• Inserting the IV device with a bevel down can minimize the risk of puncturing the distal wall.

• Once venous access is obtained, be sure to secure the device well according to hospital guidelines.

• Always use extension tubing and an infusion pump with pediatric IV infusions.

• Volume loss is treated by administering isotonic crystallized fluid boluses (lactated Ringer solution or normal saline). The amount of the bolus is usually calculated at a rate of 20 mL/kg and may be repeated based on the patient’s response.

• After any volume losses have been replaced, run the patient’s IV at maintenance rate. This rate is calculated based on the patient’s age and weight. Table 52-5 provides pediatric maintenance formulas.

TABLE 52-5 MAINTENANCE INTRAVENOUS FLUID RATES IN CHILDREN

| WEIGHT | AMOUNT PER HOUR (mL) |

|---|---|

| 1–10 kg | 100 mL/kg/24 hr |

| 10–20 kg | 1000 mL plus 50 mL/kg for each additional kilogram over 10 (up to 20 kg), given over 24 hr |

| ≥21 kg | 1500 mL plus 20 mL/kg for each additional kilogram over 21, given over 24 hr |

Data from National Institutes of Health. (2008, June 23). Intravenous fluid management. Retrieved from http://www.cc.nih.gov/ccc/pedweb/pedsstaff/ivf.html

Pediatric Cardiopulmonary Arrest

The pediatric patient in respiratory failure or shock is at high risk for further decompensation and subsequent cardiopulmonary arrest. Advanced life support interventions must be implemented emergently. Begin with basic life support (BLS) maneuvers by immediately opening the airway, assisting ventilations, and initiating cardiac compressions as needed. Refer to current American Heart Association Basic Life Support and Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS) guidelines for pediatric resuscitation.7 Be sure to facilitate family presence at the bedside and to arrange for transfer to a higher level of care, such as admission to a pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) or to another facility. Start this process early.

Apparent Life-Threatening Events

An apparent life-threatening event (ALTE) is defined as an episode that is frightening to the observer because of a change in the infant’s breathing.8 Previously this condition was referred to as a “near-miss” sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). ALTEs are characterized by a combination of the following:

• Apnea: central (no respiratory effort) or obstructive

• Color change: cyanosis or pallor

• Marked change in muscle tone (limp)

• Events immediately preceding the ALTE (e.g., recent illness, immunizations, daily activities)

• Usual sleep conditions (e.g., position, bedding, bed sharing)

• Precise time when ALTE occurred and association with time of last feeding or presence of fever

• Place where ALTE occurred (e.g., caregiver’s arms, crib, bed, car)

• State of infant when found (e.g., awake or asleep; position of sleep, face covered or uncovered)

• If awake, activities during ALTE (e.g., feeding, bathing, crying)

• Reason that led to discovery of the infant (e.g., abnormal cry)

Sudden Infant Death Syndrome

SIDS is the sudden death of a child (generally <12 months old) that remains unexplained after postmortem examination, investigation of the death scene, and review of the patient’s case history. SIDS is a diagnosis of exclusion. The peak SIDS incidence is between 2 and 4 months of age.10

Etiology

The cause of SIDS is unknown, but several different factors may cause infant death. SIDS incidents occur most often between the ages of 0 and 6 months, with Native Americans and African Americans having the highest incidence.10 It occurs most often in the winter months, with January having the peak incidence.11 SIDS affects boys more often than girls.10 Almost all SIDS deaths occur without any warning or symptoms and usually when the infant is thought to be asleep.11

The following have been linked to an increased risk of SIDS:

Therapeutic Interventions

Pacifiers at naptime and bedtime can reduce the risk of SIDS.12 It is thought that the pacifier may keep the airway open more and also that the infant does not fall into a deep sleep. Other preventative measures include the following:

Most therapeutic interventions are directed toward the grieving family. These include the following:

• Permit the family to say goodbye before discontinuing resuscitation.

• Allow family members to hold the deceased infant (as permitted by municipal rules related to handling of the body by family members); do not rush them.

• Provide mementos such as a lock of hair, footprints, or handprints (these also can be obtained from the funeral home).

• Consult with the antepartum and postpartum nursing staff as they may have a protocol for infant loss that may be helpful in the loss of an infant in the ED.

• Explain to the family that it is unlikely they did anything to cause the infant’s death and that there was nothing they could have done to prevent it.

• Describe what will happen next: autopsy, then release to the funeral home.

• Encourage follow-up grief counseling and support groups.

• Many SIDS websites are available as resources for distraught families and staff members.

General Pediatric Emergencies

Pediatric Fever

Fever is the most common single complaint in pediatric patients and accounts for as many as 20% to 25% of pediatric visits to the ED.13 Fever is defined in a neonate as 38°C (100.4°F).14 Hyperthermia has a variety of causes, most commonly infection, but it also can result from poisoning, dehydration, heat exposure, metabolic disorders, or collagen-vascular diseases. The presence of fever on presentation, or fever reported at home, may influence triage and treatment decisions in pediatric patients who are at increased risk for sepsis or other serious illness (e.g., neonate, immunocompromised).

Therapeutic Interventions

• Administer fluids (oral, subcutaneous, or IV) based on the pediatric patient’s need.

• Dress the patient in a minimal amount of lightweight clothing.

• Administer antipyretic medications as indicated14:

• Give the patient a tepid bath or shower.

• Identify and treat the cause of the elevated temperature.

• A fever of unknown cause in an infant under 3 months of age requires a septic workup that includes blood cultures and urine culture (urine must be obtained via urinary catheterization). A lumbar puncture is also performed in most febrile infants less than 2 to 3 months of age without an identified source of fever.

Respiratory Emergencies

Airway Obstruction

• Level of consciousness: alert, irritable, lethargic

• Skin signs: color, temperature, moistness

• Signs of hypoxia: circumoral or general cyanosis, rapid respiratory rate

• Upper airway obstruction: stridor, object in the mouth, oropharyngeal edema

• Use of accessory muscles of respiration: retractions, abdominal muscle use, nasal flaring

• Unusual breath odors: ketones, chemicals, ethanol

• Abnormal lung sounds: wheezes, stridor, crackles, absent

• Vital signs (be sure to include temperature and pain assessment)

• Evidence of dehydration: poor skin turgor, dry mucosa, lack of tears, sunken fontanel

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree