Paracentesis and Diagnostic Peritoneal Lavage

Lena M. Napolitano

Abdominal Paracentesis

Indications

Abdominal paracentesis is a simple procedure that can be easily performed at the bedside in the intensive care unit and may provide important diagnostic information or therapy in critically ill patients with ascites. Diagnostic abdominal paracentesis is usually performed to determine the exact etiology of the accumulated ascites or to ascertain whether infection is present, as in spontaneous bacterial peritonitis [1]. It can also be used in any clinical situation in which the analysis of a sample of peritoneal fluid might be useful in ascertaining a diagnosis and guiding therapy. The evaluation of ascites should therefore include a diagnostic paracentesis with ascitic fluid analysis.

As a therapeutic intervention, abdominal paracentesis is usually performed to drain large volumes of abdominal ascites [2]. Ascites is the most common presentation of decompensated cirrhosis, and its development heralds a poor prognosis, with a 50% 2-year survival rate. Effective first-line therapy for ascites includes sodium restriction (2 g per day), use of diuretics, and large-volume paracentesis. Ideally, a combination of a loop diuretic and aldosterone antagonist is used. When tense or refractory ascites is present, large-volume paracentesis is safe and effective and has the advantage of producing immediate relief from ascites and its associated symptoms [3]. Ten percent of cirrhotic patients develop refractory ascites, which carries substantial morbidity and has a 1-year survival of less than 50%. A Cochrane Database Systematic Review compared transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunts (TIPS) versus paracentesis standard treatment in patients with refractory ascites due to cirrhosis. TIPS removed ascites more effectively than paracentesis, and after 12 months, the beneficial effects of TIPS on ascites was still present. However, no differences in mortality, gastrointestinal bleeding, infection or sepsis, acute renal failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulation were identified, and hepatic encephalopathy occurred significantly more often in the TIPS group [4].

Therapeutic abdominal paracentesis can be palliative by diminishing abdominal pain from distention or improving pulmonary function by allowing better diaphragmatic excursion in patients who have ascites refractory to aggressive medical management [5]. Paracentesis is also used for percutaneous decompression of resuscitation-induced abdominal compartment syndrome related to the development of acute tense ascites [6,7].

Techniques

Before abdominal paracentesis is initiated, a catheter must be inserted to drain the urinary bladder, and correction of any underlying coagulopathy or thrombocytopenia should be considered. A consensus statement from the International Ascites Club states that “there are no data to support the correction of mild coagulopathy with blood products prior to therapeutic paracentesis, but caution is needed when severe thrombocytopenia is present” [3]. The practice guideline from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases states that routine correction of prolonged prothrombin time or thrombocytopenia is not required when experienced personnel perform paracentesis [8]. This has been confirmed in a study of 1,100 large-volume paracenteses in 628 patients [9]. But in critically ill patients, there is still uncertainty as to the optimal platelet count and prothrombin time for the safe conduct of paracentesis.

The patient must next be positioned correctly. If he or she is critically ill, the procedure is performed in the supine position. If the patient is clinically stable and abdominal paracentesis is being performed for therapeutic volume removal of ascites, the patient can be placed in the sitting position, leaning slightly forward, to increase the total volume of ascites removed.

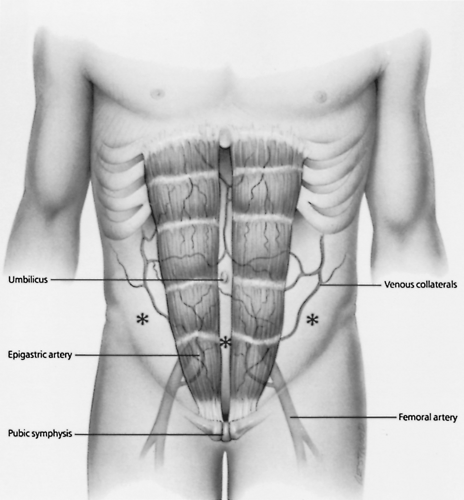

The site for paracentesis on the anterior abdominal wall is then chosen (Fig. 14-1). The preferred site is in the lower abdomen, just lateral to the rectus abdominis muscle and inferior to the umbilicus. It is important to stay lateral to the rectus abdominis muscle to avoid injury to the inferior epigastric artery and vein. In patients with chronic cirrhosis and caput medusae (engorged anterior abdominal wall veins), these visible vascular structures must be avoided. Injury to these veins can cause significant bleeding because of underlying portal hypertension and may result in hemoperitoneum. The left lower quadrant of the abdominal wall is preferred over the right lower quadrant for abdominal paracentesis because critically ill patients often have cecal distention. The ideal site is therefore in the left lower quadrant of the abdomen, lateral to the rectus abdominis muscle in the midclavicular line and inferior to the umbilicus. It has also been determined that the left lower quadrant is significantly thinner and the depth of ascites greater compared with the infraumbilical midline position, confirming the left lower quadrant as the preferred location for paracentesis [10].

If the patient had previous abdominal surgery limited to the lower abdomen, it may be difficult to perform a paracentesis in the lower abdomen, and the upper abdomen may be chosen. The point of entry, however, remains lateral to the rectus

abdominis muscle in the midclavicular line. If there is concern that the ascites is loculated because of previous abdominal surgery or peritonitis, abdominal paracentesis should be performed under ultrasound guidance to prevent iatrogenic complications.

abdominis muscle in the midclavicular line. If there is concern that the ascites is loculated because of previous abdominal surgery or peritonitis, abdominal paracentesis should be performed under ultrasound guidance to prevent iatrogenic complications.

Abdominal paracentesis can be performed by the needle technique, the catheter technique, or with ultrasound guidance. Diagnostic paracentesis usually requires 20 to 50 mL peritoneal fluid and is commonly performed using the needle technique. However, if large volumes of peritoneal fluid are required (i.e., for cytologic examination), the catheter technique is used because it is associated with a lower incidence of complications. Therapeutic paracentesis, as in the removal of large volumes of ascites, should always be performed with the catheter technique. Ultrasound guidance can be helpful in diagnostic paracentesis using the needle technique or in therapeutic paracentesis with large volume removal using the catheter technique.

Needle Technique

With the patient in the appropriate position and the access site for paracentesis determined, the patient’s abdomen is prepared with 10% povidone-iodine solution and sterilely draped. If necessary, intravenous sedation is administered to prevent the patient from moving excessively during the procedure (see Chapter 20). Local anesthesia, using 1% or 2% lidocaine with 1:200,000 epinephrine is infiltrated into the site. A skin wheal is created with the local anesthetic, using a short 25- or 27-gauge needle. Then, using a 22-gauge, 1.5-inch needle, the local anesthetic is infiltrated into the subcutaneous tissues and anterior abdominal wall, with the needle perpendicular to the skin. Before the anterior abdominal wall and peritoneum are infiltrated, the skin is pulled taut inferiorly, allowing the peritoneal cavity to be entered at a different location than the skin entrance site, thereby decreasing the chance of ascitic leak. This is known as the Z-track technique. While tension is maintained inferiorly on the abdominal skin, the needle is advanced through the abdominal wall fascia and peritoneum, and local anesthetic is injected. Intermittent aspiration identifies when the peritoneal cavity is entered, with return of ascitic fluid into the syringe. The needle is held securely in this position with the left hand, and the right hand is used to withdraw approximately 20 to 50 mL ascitic fluid into the syringe for a diagnostic paracentesis.

Once adequate fluid is withdrawn, the needle and syringe are withdrawn from the anterior abdominal wall and the paracentesis site is covered with a sterile dressing. The needle is removed from the syringe, because it may be contaminated with skin organisms. A small amount of peritoneal fluid is sent in a sterile container for Gram’s-stained smear and culture and sensitivity testing. The remainder of the fluid is sent for appropriate studies, which may include cytology, cell count and differential, protein, specific gravity, amylase, pH, lactate dehydrogenase, bilirubin, triglycerides, and albumin. A serum to ascites albumin gradient (SAAG) greater than 1.1 g per dL is indicative of

portal hypertension and cirrhosis (Table 14-1) [11]. Peritoneal fluid can be sent for smear and culture for acid-fast bacilli if tuberculous peritonitis is in the differential diagnosis.

portal hypertension and cirrhosis (Table 14-1) [11]. Peritoneal fluid can be sent for smear and culture for acid-fast bacilli if tuberculous peritonitis is in the differential diagnosis.

TABLE 14-1. Etiologies of Ascites Based on Normal or Diseased Peritoneum and Serum to Ascites Albumin Gradient (SAAG) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Catheter Technique

The patient is placed in the proper position, and the anterior abdominal wall site for paracentesis is prepared and draped in the usual sterile fashion. Aseptic technique is used throughout the procedure. The site is anesthetized with local anesthetic as described for the needle technique. A 22-gauge, 1.5-inch needle attached to a 10-mL syringe is used to document the free return of peritoneal fluid into the syringe at the chosen site. This needle is removed from the peritoneal cavity and a catheter-over-needle assembly is used to gain access to the peritoneal cavity. If the anterior abdominal wall is thin, an 18- or 20-gauge angiocath can be used as the catheter-over-needle assembly. If the anterior abdominal wall is quite thick, as in obese patients, it may be necessary to use a long (5.25-inch) catheter-over-needle assembly (18- or 20-gauge) or a percutaneous single-lumen central venous catheter (18- or 20-gauge) and gain access to the peritoneal cavity using the Seldinger technique.

The peritoneal cavity is entered as for the needle technique. The catheter-over-needle assembly is inserted perpendicular to the anterior abdominal wall using the Z-track technique; once peritoneal fluid returns into the syringe barrel, the catheter is advanced over the needle, the needle is removed, and a 20- or 50-mL syringe is connected to the catheter. The tip of the catheter is now in the peritoneal cavity and can be left in place until the appropriate amount of peritoneal fluid is removed. This technique, rather than the needle technique, should be used when large volumes of peritoneal fluid must be removed, because complications (e.g., intestinal perforation) may occur if a needle is left in the peritoneal space for an extended period.

When the Seldinger technique is used in patients with a large anterior abdominal wall, access to the peritoneal cavity is initially gained with a needle or catheter-over-needle assembly. A guidewire is then inserted through the needle and an 18- or 20-gauge single-lumen central venous catheter threaded over the guidewire. It is very important to use the Z-track method for the catheter technique to prevent development of an ascitic leak, which may be difficult to control and may predispose the patient to peritoneal infection.

Ultrasound Guidance Technique

Patients who have had previous abdominal surgery or peritonitis are predisposed to abdominal adhesions, and it may be quite difficult to gain free access into the peritoneal cavity for diagnostic or therapeutic paracentesis. Ultrasound-guided paracentesis can be very helpful in this population by providing accurate localization of the peritoneal fluid collection and determining the best abdominal access site. This procedure can be performed using the needle or catheter technique as described above, depending on the volume of peritoneal fluid to be drained. Once the fluid collection is localized by the ultrasound probe, the abdomen is prepared and draped in the usual sterile fashion. A sterile sleeve can be placed over the ultrasound probe so that there is direct ultrasound visualization of the needle or catheter as it enters the peritoneal cavity. The needle or catheter is thus directed to the area to be drained, and the appropriate amount of peritoneal or ascitic fluid is removed. If continued drainage of a loculated peritoneal fluid collection is desired, the radiologist can place a chronic indwelling peritoneal catheter using a percutaneous guidewire technique (see Chapter 21).

The use of ultrasound guidance for drainage of loculated peritoneal fluid collections has markedly decreased the incidence of iatrogenic complications related to abdominal paracentesis. If the radiologist does not identify loculated ascites on the initial ultrasound evaluation and documents a large amount of peritoneal fluid that is free in the abdominal cavity, he or she can then indicate the best access site by marking the anterior abdominal wall with an indelible marker. The paracentesis can then be performed by the clinician and repeated whenever necessary. This study can be performed at the bedside in the intensive care unit with a portable ultrasound unit.

Complications

The most common complications related to abdominal paracentesis are bleeding and persistent ascitic leak. Because most patients in whom ascites have developed also have some component of chronic liver disease with associated coagulopathy

and thrombocytopenia, it is very important to consider correction of any underlying coagulopathy before proceeding with abdominal paracentesis. In addition, it is very important to select an avascular access site on the anterior abdominal wall. The Z-track technique is very helpful in minimizing persistent ascitic leak and should always be used. Another complication associated with abdominal paracentesis is intestinal or urinary bladder perforation, with associated peritonitis and infection. Intestinal injury is more common when the needle technique is used. Because the needle is free in the peritoneal cavity, iatrogenic intestinal perforation may occur if the patient moves or if intraabdominal pressure increases with Valsalva maneuver or coughing. Urinary bladder injury is less common and underscores the importance of draining the urinary bladder with a catheter before the procedure. This injury is more common when the abdominal access site is in the suprapubic location; therefore, this access site is not recommended. Careful adherence to proper technique of paracentesis minimizes associated complications.

and thrombocytopenia, it is very important to consider correction of any underlying coagulopathy before proceeding with abdominal paracentesis. In addition, it is very important to select an avascular access site on the anterior abdominal wall. The Z-track technique is very helpful in minimizing persistent ascitic leak and should always be used. Another complication associated with abdominal paracentesis is intestinal or urinary bladder perforation, with associated peritonitis and infection. Intestinal injury is more common when the needle technique is used. Because the needle is free in the peritoneal cavity, iatrogenic intestinal perforation may occur if the patient moves or if intraabdominal pressure increases with Valsalva maneuver or coughing. Urinary bladder injury is less common and underscores the importance of draining the urinary bladder with a catheter before the procedure. This injury is more common when the abdominal access site is in the suprapubic location; therefore, this access site is not recommended. Careful adherence to proper technique of paracentesis minimizes associated complications.

In patients who have large-volume chronic abdominal ascites, such as that secondary to hepatic cirrhosis or ovarian carcinoma, transient hypotension, and paracentesis-induced circulatory dysfunction (PICD) syndrome may develop during therapeutic abdominal paracentesis. PICD is characterized by hyponatremia, azotemia, and an increase in plasma renin activity. A significant inverse correlation between changes in plasma renin activity and systemic vascular resistance has been demonstrated in those patients following paracentesis, suggesting that peripheral arterial vasodilation may be responsible for this circulatory dysfunction. Evidence is accumulating that PICD is secondary to an accentuation of an already established arteriolar vasodilation with multiple etiologies, including the dynamics of paracentesis (the rate of ascitic fluid extraction), release of nitric oxide from the vascular endothelium, and mechanical modifications due to abdominal decompression [12].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree