PANCREATITIS

Pancreatitis is an inflammatory process of the pancreas that may be limited to just the pancreas, may affect surrounding tissues, or may cause remote organ system dysfunction. Most patients will only have one episode of acute pancreatitis, whereas 15% to 30% will have at least one recurrence.1,2,3 Between 5% and 25% of patients will ultimately develop chronic pancreatitis.2,3

Most cases (~80%) involve only mild inflammation of the pancreas, a disease state with a mortality rate of <1%, which generally resolves with only supportive care.1,4 A small proportion of patients suffer from more severe disease that may involve pancreatic necrosis, inflammation of surrounding tissues, and organ failure, leading to a 30% mortality rate.5,6

The annual incidence of pancreatitis varies among nations and regions. Developed countries have a higher incidence of pancreatitis than developing countries. In general, men and women suffer from acute pancreatitis with equal frequency, although alcohol-associated acute pancreatitis is more common in men, while gallstone-induced pancreatitis is more common in women.7 Blacks are affected two- to threefold more often than whites but have a mortality rate equal to the general population.3,8 The incidence of acute pancreatitis varies with age, with a peak in middle age.9 Other risk factors include smoking, obesity, and diabetes mellitus.9,10

Factors associated with acute pancreatitis are listed in Table 79-1. Most cases are related to either gallstones or alcohol consumption. About 5% of all patients who undergo endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for treatment of gallstones develop pancreatitis within 30 days.11

| Common | Idiopathic (10%–20%)13 |

| Uncommon | Hypertriglyceridemia (triglycerides >1000 milligrams/dL) (1%–4%)14 Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography11 Drugs (1.4%–2%) |

| More uncommon (total <8% of cases) | Abdominal trauma Postoperative complications Hyperparathyroidism Infection (bacterial, viral, or parasitic) Autoimmune disease Tumor (pancreatic, ampullary) Hypercalcemia Cystic fibrosis |

| Rare | Ischemia Posterior penetrating ulcer Toxin exposure |

| Unknown | Congenital abnormalities15 |

The nature of the association between alcohol use and acute pancreatitis is unclear. Some studies suggest that consumption of a large amount of alcohol over a short period of time is a more important factor than chronic alcohol use.16 However, others suggest that at least 5 years of heavy alcohol use are required before alcohol can reliably be considered the cause.17

More than 120 drugs have been linked to acute pancreatitis but together account for fewer than 2% of cases. Table 79-2 lists the commonly used drugs found by two sets of authors to be most well linked to acute pancreatitis based on number of case reports and recurrence after drug reexposure.18,19

Acetaminophen Amiodarone Cannabis Carbamazepine Chlorothiazide/hydrochlorothiazide Codeine (and other opiates) Dexamethasone (and other steroids) Enalapril Estrogens Erythromycin Furosemide Losartan Methimazole Metronidazole Pravastatin/simvastatin Procainamide Tetracycline Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole Tuberculosis antibiotics (dapsone, isoniazid, rifampin) |

The pathophysiology of pancreatitis is not completely understood. Under normal circumstances, trypsinogen is produced in the pancreas and secreted into the duodenum where it is converted into the protease trypsin. In acute pancreatitis, for unclear reasons, trypsin is activated within the pancreatic acinar cells. Activation continues in an unregulated fashion and elimination of activated trypsin is inhibited, resulting in high pancreatic levels of activated trypsin. Activated trypsin in turn activates other digestive enzymes, complements, and kinins, leading to pancreatic autodigestion, injury, and inflammation. Pancreatic injury activates local production of inflammatory mediators, which cause further inflammation.20,21 Fortunately, most cases never progress beyond local inflammation. However, in a minority of cases, termed necrotizing pancreatitis, pancreatic injury progresses to involve surrounding tissue or possibly remote organ systems.22 The release of inflammatory mediators from the pancreas, in particular from the acinar cells, and extrapancreatic organs such as the liver leads to remote organ injury and failure, the systemic inflammatory response syndrome, multiorgan failure, and even death.20,21,22

Acute pancreatitis causes acute, severe, and persistent abdominal pain, usually associated with nausea, vomiting, anorexia, and decreased oral intake.23 The pain is located in the epigastrium or occasionally in the left or right upper quadrants. Pain may radiate to the back, chest, or flanks. Pain may worsen with oral intake or laying supine and may improve with sitting up with the knees flexed.24,25,26 Other symptoms include abdominal swelling, diaphoresis, hematemesis, and shortness of breath. Pain described as lower abdominal pain or dull or colicky pain is highly unlikely to be pancreatitis.25

The vital signs may be abnormal, with tachycardia, tachypnea, fever, or hypotension. Pain is confined to the epigastrium or upper abdomen, often with guarding and decreased bowel sounds.23 Occasionally patients will be jaundiced, pale, or diaphoretic.

Rare physical findings associated with late, severe necrotizing pancreatitis include Cullen’s sign (bluish discoloration around the umbilicus signifying hemoperitoneum), Grey-Turner sign (reddish-brown discoloration along the flanks signifying retroperitoneal blood or extravasation of pancreatic exudate), and erythematous skin nodules from focal subcutaneous fat necrosis.26,27

Formal diagnosis is based on at least two of three criteria: (1) clinical presentation consistent with acute pancreatitis, (2) a serum lipase or amylase value elevated above the upper limit of normal, or (3) imaging findings characteristic of acute pancreatitis (IV contrast-enhanced CT, MRI, or transabdominal US).25,28 The differential diagnosis is wide and consists of all causes of upper abdominal pain, as detailed in chapter 71, “Acute Abdominal Pain.”

There is no gold standard laboratory diagnosis for acute pancreatitis. Two current guidelines recommend that the amylase or lipase value be at least three times the upper limit of normal;25,28 some recommend a lipase of two times normal or an amylase of three times normal in a patient with the appropriate clinical presentation;29 and some recommend that any elevation above normal is consistent with the diagnosis.23 Normal levels for amylase and lipase are based on values in young, healthy patients, making it difficult to determine applicable levels for older patients or those with multiple comorbidities.29 Consequently, the combination of an elevated laboratory value with a clinical presentation consistent with pancreatitis is key for diagnosis.25

Amylase is not a good choice for diagnosis.25 Amylase rises within a few hours after the onset of symptoms, peaks within 48 hours, and normalizes in 3 to 5 days.29 About 20% of patients with pancreatitis, most of whom have alcohol- and hypertriglyceridemia-related disease, will have a normal amylase.30 This fact, along with the rapid decrease in amylase after symptom onset, gives amylase a sensitivity of about 70%, with a positive predictive value ranging from 15% to 72%. 23 Amylase can be elevated in multiple non–pancreas-related diseases, such as renal insufficiency, salivary gland diseases, acute appendicitis, cholecystitis, intestinal obstruction or ischemia, and gynecologic diseases, lowering specificity for pancreatitis.23,30

Lipase is more specific to pancreatic injury and remains elevated for longer after onset of symptoms than amylase. Lipase may be elevated in diabetics at baseline and in other nonpancreatic diseases such as renal disease, appendicitis, and cholecystitis, but it is less associated with nonpancreatic diseases than amylase.25,31 Lipase is more sensitive in patients with a delayed presentation and in cases of alcoholic or hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis.29

When an elevation of both lipase and amylase is required to diagnose pancreatitis, specificity is increased and sensitivity is decreased compared to using either test alone, but there is no evidence that adding amylase to a nondiagnostic lipase improves diagnostic accuracy over lipase alone.29

The urine trypsinogen-2 dipstick test is a rapid, noninvasive test with high sensitivity (82%) and specificity (94%).32 However, given its current limited availability, it is not included as part of the diagnostic criteria for pancreatitis.28

In addition to serum lipase and amylase, obtain blood studies to evaluate renal and liver function, electrolyte status, glucose level, WBC count, and hemoglobin/hematocrit. These lab results help the clinician predict disease severity and outcome (detailed below), optimize the clinical status of the patient, identify complications that need immediate treatment (cholangitis, organ failure), and assess effectiveness of treatment.

An alanine aminotransferase of >150 U/L within the first 48 hours of symptoms predicts gallstone pancreatitis with a greater than 85% positive predictive value.33

Imaging can identify the cause of pancreatitis and can identify complications and severity. For patients with acute pancreatitis where gallstones have not been excluded, obtain a transabdominal US in the ED to detect gallstone pancreatitis.3,28,34 For any patient with respiratory complaints, obtain a chest radiograph to evaluate for pleural effusions and pulmonary infiltrates, both associated with more severe pancreatitis.

In patients who meet the clinical presentation and laboratory criteria, routine early CT, with or without IV or PO contrast, is not recommended for multiple reasons. Most patients have uncomplicated disease and are readily diagnosed by clinical and laboratory criteria. There is no evidence that early CT, with or without contrast, improves clinical outcomes.28,35,36 Peripancreatic fluid collections or pancreatic necrosis detected by CT of any kind within the first few days of symptoms generally require no treatment, and the complete extent of these local complications is usually not appreciated until at least 3 days after onset of symptoms. The magnitude of morphologic change on imaging studies does not necessarily correlate with disease severity.37 Finally, IV contrast infusion can cause allergic reactions, nephrotoxicity, and worsening of pancreatitis.38

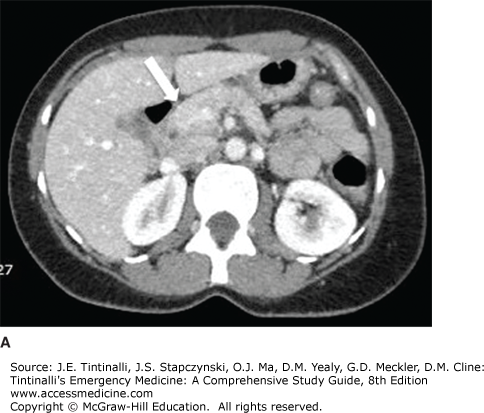

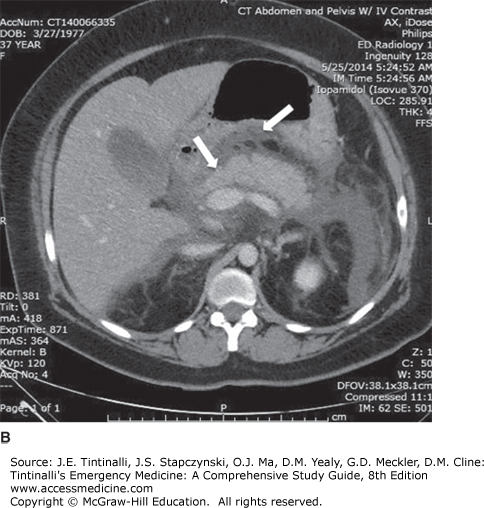

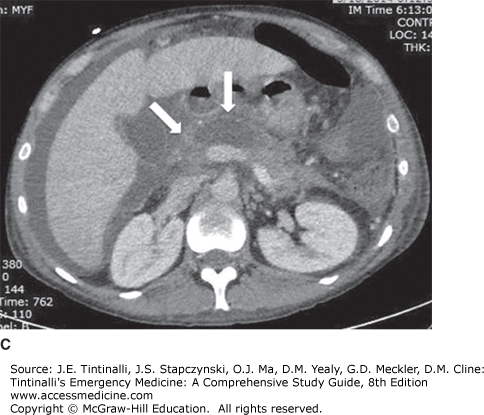

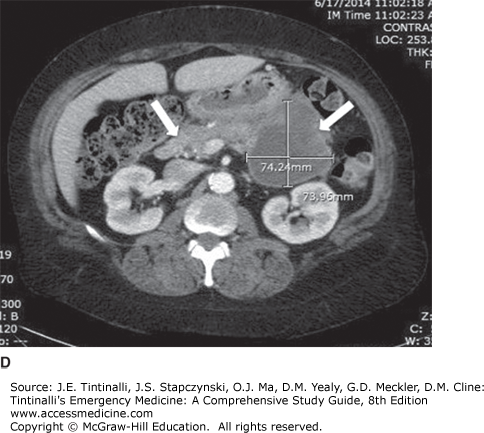

If the clinical diagnosis of acute pancreatitis is in doubt, consider further evaluation with IV contrast abdominal CT. Characteristic findings include: (1) pancreatic parenchymal inflammation with or without peripancreatic fat inflammation; (2) pancreatic parenchymal necrosis or peripancreatic necrosis; (3) peripancreatic fluid collection; or (4) pancreatic pseudocyst.25,39 Figure 79-1A–D compares CT image of a normal pancreas to images in various complications. Although noncontrast MRI is not readily available to the ED, this imaging modality can identify the complications of pancreatitis and choledocholithiasis. It can be an alternative for patients with renal failure, patients who are allergic to IV contrast, or pregnant patients.40

FIGURE 79-1.

Abdominal IV contrast-enhanced CT scans showing: A. normal pancreas (arrow) with smooth outer contours, clear demarcation between pancreas and surrounding tissues, and without peripancreatic fluid; B. mild pancreatitis with indistinct pancreatic borders (left arrow), pancreatic edema, and peripancreatic fluid (right arrow); C. edematous pancreas with indistinct borders (left arrow) and area of nonenhancing parenchyma pancreatic necrosis with area of acute pancreatic necrosis (low attenuation representing nonenhancing parenchyma; right arrow); and D. edematous pancreas with indistinct pancreatic borders (left arrow) and a pseudocyst in the pancreatic tail (right arrow). [Images contributed by Bart Besinger, MD, FAAEM.]

Treatment is supportive and symptomatic therapy (Table 79-3). No specific medication effectively treats acute pancreatitis; however, early aggressive hydration decreases morbidity and mortality.41,42,43 The benefit of fluid resuscitation may result from increased micro- and macrocirculatory support of the pancreas, which prevents complications such as pancreatic necrosis.44

| Treatment | Comments |

|---|---|

| Aggressive crystalloid therapy | Lactated Ringer’s preferably 2.5–4 L, at least 250–500 mL/h or 5–10 mL/kg/h Use caution in congestive heart failure, renal insufficiency Monitor response: – Hematocrit 35%–44% – Maintain normal creatinine – Heart rate <120 beats/min – Mean arterial pressure 65–85 mm Hg – Urine output 0.5–1 mL/kg/h (if no renal failure) |

| Vital signs/pulse oximetry | Monitor closely/frequently; initially at least every 2 h, but patients may require more frequent monitoring |

| Electrolyte repletion | Correct low ionized calcium, hypomagnesemia Control hyperglycemia |

| Pain control | Parenteral narcotics |

| Supplemental oxygen | As needed for respiratory insufficiency |

| Antiemetics | Control nausea/vomiting NPO status Nasogastric tube/suction typically not indicated |

| Antibiotics | If known or strongly suspected infection, give appropriate antibiotics based on cause Prophylactic antibiotics and antibiotics for mild pancreatitis not indicated |

| Consultation for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography | In first 24 h for those with documented biliary obstruction or cholangitis |

Provide fluid resuscitation. Fluid loss results from vomiting, third spacing, increased insensible losses, and decreased oral intake. Patients generally need 2.5 to 4 L of fluid with at least one third delivered in the first 12 to 24 hours.25,28 The specific rate of fluid delivery depends on the patient’s clinical status. In the situation of renal or heart failure, deliver fluid more slowly to prevent complications such as volume overload, pulmonary edema, and abdominal compartment syndrome. Crystalloids are the resuscitation fluids of choice. Normal saline in large volumes may cause a nongap hyperchloremic acidosis and can worsen pancreatitis, possibly by activating trypsinogen and making acinar cells more susceptible to injury.25,45 A single randomized study showed a decreased incidence of systemic inflammatory response syndrome in patients who received lactated Ringer’s instead of 0.9% normal saline.45 Regardless of which fluid is selected, monitor vital signs and urine output as responses to hydration.

Control pain and nausea. Pain control is best achieved with IV opioid analgesics. Initially, place patients on NPO (nothing by mouth) status and administer antiemetics. There is no benefit to nasogastric intubation.

Prolonged bowel and pancreas rest increases gut atrophy and bacterial translocation, leading to infection and increasing morbidity and mortality.46 In the ED, if nausea and vomiting have resolved and pain has decreased, transition the patient to oral pain medications and small amounts of food.47 A low-fat solid foods diet provides more calories than a clear liquid diet and is safe.48

Acute pancreatitis by itself is not a source of infection, and prophylactic use of antibiotics and antifungals is not recommended.49 Administer antibiotics if a source of infection is demonstrated, such as cholangitis, urinary tract infection, pneumonia, or infected pancreatic necrosis.49

Although most patients with acute pancreatitis have mild uncomplicated disease, a small percentage of patients have more severe disease. In the ED, it is difficult to distinguish disease severity, because most patients present so early in the disease course that complications that define moderately severe or severe disease are not evident. Moderately severe acute pancreatitis is characterized by transient organ failure (<48 hours), local complications, or systemic complications. Severe disease includes one or more local or systemic complications and persistent organ failure (>48 hours). Critical acute pancreatitis is persistent organ failure and infected pancreatic necrosis.50

Local complications involve the pancreas and surrounding tissues and include acute peripancreatic fluid collections, pancreatic pseudocyst, acute pancreatic or peripancreatic necrosis, walled off necrosis, gastric outlet dysfunction, splenic and portal vein thrombosis, and colonic inflammation/necrosis.22 These are not usually well demonstrated on CT scan until at least 72 hours after the onset of symptoms. Suspect local complications in patients who have persistent or recurrent abdominal pain, an increase in pancreatic enzyme levels after an initial decrease, new or worsening organ dysfunction, or sepsis (fever, increased WBC count).

Organ failure can be seen in any system, but three organ systems are particularly susceptible: cardiovascular, respiratory, and renal. Because of the susceptibility of these three organ systems, pay special attention during the patient’s initial evaluation.

Other possible complications of acute pancreatitis are listed in Table 79-4.

| Pancreatic | Peripancreatic | Extrapancreatic | |

|---|---|---|---|

Fluid collection Necrosis Sterile or infected Acute or walled off Abscess Ascites | Fluid collection Necrosis Intra-abdominal or retroperitoneal hemorrhage Pseudoaneurysm (of contiguous visceral arteries, e.g., the splenic) Bowel inflammation, infarction, or necrosis Biliary obstruction with jaundice Splenic or portal vein thrombosis | Cardiovascular Hypotension Hypovolemia Myocardial depression Myocardial infarction Pericardial effusion Pulmonary Hypoxemia Atelectasis Pleural effusion (with or without fistula) Pulmonary infiltrates Acute respiratory distress syndrome Respiratory failure Hematologic Disseminated intravascular coagulation | GI Peptic ulcer disease/erosive gastritis GI perforation GI bleeding Duodenal or stomach obstruction Splenic infarction Renal Oliguria Azotemia Acute renal failure Thrombosis of renal artery or vein Metabolic Hyperglycemia Hypocalcemia Hypertriglyceridemia |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree