PAIN: SCROTAL

CATHERINE E. PERRON, MD AND STEVEN S. BIN, MD

Acute scrotal swelling or pain in a child is a potential surgical emergency requiring prompt evaluation. Although some causes of acute scrotal swelling are benign and require only observation and reassurance, other causes may lead to the rapid loss of a testis if diagnosis or treatment is delayed (testicular torsion). Many diagnoses in cases of scrotal pain are most reliably made clinically, differentiating by age, historical features relating to the evolution of pain and associated symptoms, and physical examination findings.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

An understanding of scrotal anatomy and development is important for rapid assessment. The structures contained in the scrotum include the testis; the epididymis; appendages of the testis; and the nerve, vascular, and lymphatic structures that constitute the spermatic cord and traverse the inguinal canal into the scrotum (Fig. 56.1). At 32 to 40 weeks’ gestation, the testis descends through the inguinal canal from the abdomen to the scrotum. The testis descends within the process vaginalis, which is an outpouching of the peritoneal cavity. The abdominal portion of the process vaginalis then closes and the remaining portion, called the tunica vaginalis, is a potential space that encompasses the anterior two-thirds of the testicle. Within this space, fluids of various etiologies can collect. The testis, its related structures, and the layers of tissue that surround each testis in the scrotum may each relate to the pathology seen. Acute conditions of the scrotum may involve ischemia, inflammation, trauma, and tumor. These processes can alter blood flow to structures within the scrotum, making perfusion imaging modalities useful when correlated with clinical examination.

FIGURE 56.1 Anatomy of the scrotal contents.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

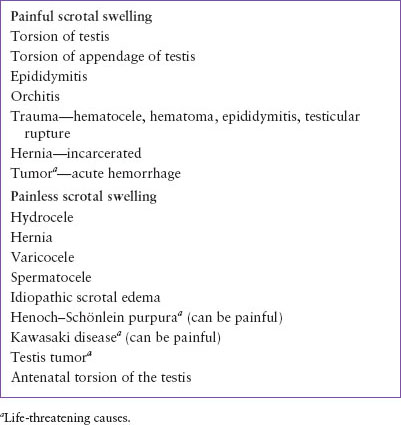

Table 56.1 lists the principal causes of acute scrotal swelling, and Table 56.2 provides the most common diagnoses by age.

CAUSES OF PAINFUL SCROTAL SWELLING

Torsion of the Testis

Testicular torsion or twisting of the spermatic cord and its contents threatens the survival of the testis and is a true surgical emergency. Testicular torsion accounts for 10% to 15% of cases of acute scrotal pain and has two peaks in incidence; a small one in the newborn period, and a larger peak around puberty related to the increasing mass of the testis.

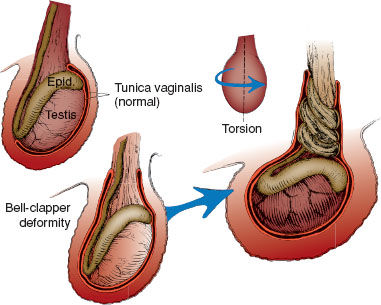

Torsion results from an inadequate fixation of the testis to the intrascrotal subcutaneous tissue (Fig. 56.2), resulting in the “bell-clapper” deformity. The testis, which hangs more freely within the tunica vaginalis in this deformity, may rotate, producing intravaginal torsion of the spermatic cord, venous engorgement of the testis, and subsequent arterial infarction (Fig. 56.3).

TABLE 56.1

CAUSES OF ACUTE SCROTAL SWELLING

FIGURE 56.2 Torsion testis. Abnormality of testicular fixation— bell-clapper deformity—permits torsion of spermatic vessels with subsequent infarction of the gonad. Epid., epididymis.

The sudden onset of severe scrotal pain and tenderness, often with radiation to the abdomen, and associated nausea and vomiting is typical. They may be associated with sports activity or mild testicular trauma that is perceived by the patient as the cause of pain. Prior episodes of similar pain that resolved may suggest intermittent torsion and spontaneous detorsion.

With torsion, the testis is acutely swollen, diffusely tender, and usually lies higher (“horizontal lie”) in the scrotum than the contralateral testis. There may be overlying erythema of the scrotal skin. The cremasteric reflex (retraction of the testis with stroking of the inner thigh) is usually absent with testicular torsion, but may be present in early or incomplete torsion. The cremasteric reflex may be absent in some boys without torsion, usually less than 6 months of age. Since pain may be referred to the abdomen, genitalia should be examined carefully in every child who complains of abdominal pain. Urinalysis is usually negative.

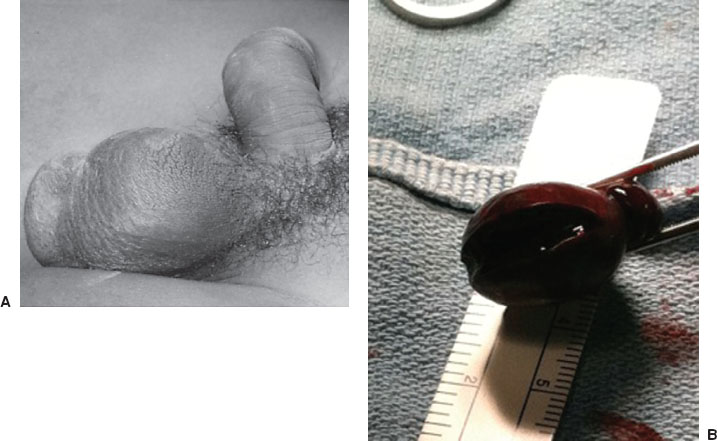

FIGURE 56.3 Torsion of testis. A: Swollen, diffusely tender testis high in the scrotum (from twisting of cord structures). B: Surgically exposed testis showing torsion of cord structures. Testis was infarcted and was removed.

The diagnosis of testicular torsion is made clinically when unilateral, acute scrotal pain presents with testicular changes, absent cremasteric reflex, and associated nausea or vomiting. Immediate surgical consultation for exploration and repair, without delay for imaging, is optimal. A clinical scoring system that takes into account the presence of nausea or vomiting (1 point), testicular swelling (2 points), hard testis on palpation (2 points), high riding testis (1 point), and absent cremasteric reflex (1 point) has been derived and validated. A score of ≥5 indicated testicular torsion with a sensitivity of 76%, specificity of 100%, and a positive predictive value of 100% (prevalence 15%). A score ≤2 excluded testicular torsion with a sensitivity of 100%, specificity of 87%, and negative predictive value of 100%.

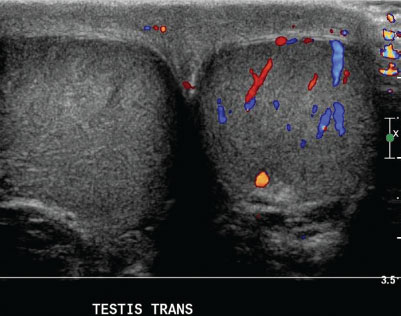

Color Doppler ultrasound evaluates the size, shape, echogenicity, and perfusion of the testes and associated structures, and confirms the absence of torsion. In testicular torsion there is decreased or absent arterial blood flow within the affected testicle (Fig. 56.4). With high sensitivity (88.9%) and specificity (98.8%) and a low false-negative rate of 1%, ultrasound is the first-line imaging modality. False-positive scans occur when testicular flow appears decreased due to a large hydrocele, abscess, hematoma, or hernia. False-negative ultrasounds occur from spontaneous detorsion, partial or intermittent torsion, or late torsion when severe, overlying scrotal edema with increased vascularity obscures the underlying ischemic testis. Limitations of Doppler sonography exist in small, lower flow prepubertal testes and due to operator-dependent nature of this test. Previously used nuclear perfusion scans are limited by associated time delay and radiation exposure. Again, imaging should not delay surgical consultation or treatment.

FIGURE 56.4 Torsion of testis. Ultrasound reveals enlarged right testicle and Doppler flow demonstrates no flow to necrotic testis.

The treatment of testicular torsion is surgical exploration, detorsion, and fixation (orchiopexy) of the torsed and contralateral testis. A nonviable testis requires orchiectomy and fixation of the contralateral testis. If a testis has been twisted sufficiently to fully obstruct its blood supply for more than 6 to 12 hours, surgical detorsion is unlikely to salvage the gonad. Salvage rates are 90% to 100% within 6 hours of symptom onset, 50% beyond 12 hours, and 10% when beyond 24 hours. However, it is impossible to determine clinically whether the torsion has been partial or total, so regardless of the estimated duration of torsion immediate surgical intervention is required.

If a child is seen within a few hours of the onset of his torsion, before severe scrotal swelling has ensued, manual detorsion of the spermatic cord to restore blood supply to the testis can be considered. Ideally, this is undertaken by a physician experienced with the technique when surgery is not an immediate option. Sedation and analgesia should be administered. If available, a Doppler stethoscope reveals decreased arterial flow to the affected testis. Since torsion typically (in two-thirds of cases) occurs in a medial direction, detorsion should initially be carried out by rotating the testis outward toward the thigh (and may require more than one rotation (Fig. 56.5). Relief of pain and a lower position of the testis in the scrotum suggest a successful outcome. Doppler stethoscope or color Doppler ultrasound should be used to confirm the return of normal arterial pulsations to the testis. Orchiopexy of both the affected testis and the contralateral one, which is malfixed in more than 50% of cases, is still recommended.

Torsion of Testicular Appendage

Several vestigial embryologic remnants are attached to the testis or epididymis that may twist around their base, producing venous engorgement, and subsequent infarction. Appendage torsion is most common in boys of ages 7 to 12 years but can occur at any age. Mild to severe scrotal pain is the usual presenting feature. There can be associated nausea or vomiting, although less commonly than in testicular torsion (see Chapter 127 Genitourinary Emergencies).

FIGURE 56.5 Torsion of testis. Because torsion typically occurs in a medial direction, manual detorsion should be attempted initially by rotating the testis outward toward the thigh.

If the child is seen early after the onset of pain, scrotal tenderness and swelling may be localized to the area of the twisted appendage, typically on the superior lateral aspect of the testis. It may be possible to have the patient point to the specific point of pain. If the site indicated is at the upper pole of the testis, a palpable, localized tender mass with the remainder of the testis being nontender, makes torsion of a testicular appendage likely. Although the classic “blue dot” sign of an infarcted appendage may be visualized through the scrotal skin, it often cannot be seen due to overlying edema. Later in the clinical course, increased scrotal tenderness and edema make differentiation from torsion of the testis difficult. The cremasteric reflex should be intact. Color Doppler ultrasound reveals normal or increased blood flow to the testis, and may demonstrate a low echogenicity structure with a central hypoechogenic area. Diagnostically, a surgical exploration may be required to be certain that torsion of the testis is not present.

The treatment of a torsed testicular or epididymal appendage is supportive with rest, support of the scrotum, and analgesic/anti-inflammatory medications. The pain usually resolves in 7 to 10 days. Rarely, removal of the torsed appendage occurs when there is severe or prolonged pain. Contralateral scrotal exploration is not indicated.

Epididymitis/Orchitis

Epididymitis is an infection or inflammation of the epididymis which occurs more frequently in sexually active adolescents and adults. In sexually active adolescents, it is most commonly associated with Chlamydia trachomatis, but Neisseria gonorrhea, Escherichia coli, Mycobacterium, and viruses are other important etiologies. In HIV-infected males, Mycobacterium, cytomegalovirus, and Cryptococcus must also be considered. Less frequently, epididymitis does occur in prepubertal and nonsexually active adolescent boys, primarily associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae, enterovirus, and adenovirus infections. Bacterial epididymitis is uncommon, but related to urinary tract infections with coliform organisms caused by structural abnormalities of the urinary tract.

The onset of swelling and pain is typically more gradual than with torsion of the testis or a testicular appendage, but can be abrupt in onset. Associated symptoms of urinary frequency, dysuria, penile discharge, or fever may be present. Scrotal edema and erythema are often present. The testicle should have a normal lie and the cremasteric reflexes should be intact. Early on, the epididymis may be selectively enlarged and tender, readily distinguished from the testis. With time, inflammation spreads to the testis (orchitis) and surrounding scrotal wall, making localization difficult. Although elevation of the scrotum may relieve pain in epididymo-orchitis (Prehn sign) it is not considered a reliable.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree