INTRODUCTION

Pain and anxiety are very common experiences for patients of all ages in the ED, and both are frequently undertreated. This is particularly true for children. There are many reasons for this, including the idea that very young children do not experience true pain or will not remember, the perceived difficulty in measuring pain and anxiety in children, fear of masking the signs and symptoms of serious disease processes, concerns that addressing pain takes too much time or effort, and lack of familiarity and comfort with medication dosing in children. These concerns should not stand in the way of providing adequate analgesia, anxiolysis, and sedation for children, however, and addressing these concerns is the primary goal of this chapter.

Caring for children in the ED requires constant attention to pain and anxiety. Common situations include fractures, lacerations, abdominal pain, lumbar puncture, incision and drainage of abscesses, and IV placement. Full procedural sedation may be necessary for invasive procedures in children. This chapter discusses pain management goals (Table 113-1) and pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic measures to minimize pain and anxiety experienced by children in the ED, with an emphasis on both basic concepts and newer developments in this topic of daily relevance to ED care providers.

Minimize physical pain and discomfort Alleviate anxiety Maximize amnesia Minimize negative psychological responses to treatment Control behavior/motion to expedite performance of procedures Maintain safety and minimize risk to patient |

ASSESSMENT OF PAIN AND ANXIETY BY AGE

The first step in the treatment of pain and anxiety in children is to quantify the severity of symptoms. The level of pain or distress may be obvious to the care provider, such as when a child has a visibly displaced fracture. Other scenarios are not as straightforward, however, such as the common complaint of abdominal pain. Preverbal and young children are especially challenging. As a result, specific pain scales have been developed for children at different developmental stages (Table 113-2). Familiarity with and application of these pain scales greatly reduces uncertainty in treating pain and anxiety in children of all ages. In addition, measuring and addressing pain is one of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Quality Measures.

Children with cognitive developmental delay may compound the challenges of assessing and treating pain and anxiety by combining the physical size and strength of an older child with the cognitive and behavioral attributes of the young. Furthermore, many of the patients in whom this “cognitive-physical mismatch” exists are medically complex and have already experienced a large number of medical encounters, including painful procedures, so baseline anxiety is high. Relying on parental pain assessment and providing empiric analgesia for procedures that are expected to be painful is the most prudent approach to these children.

A variety of pain scales have been developed for use in infants and young children, before they are able to self-report and quantify pain. These scales are based on physiologic parameters such as heart rate and observations of behavioral reactions such as crying, facial expressions, and activity level. In the United States, the FLACC Scale© (Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability) is most commonly used.

Beginning at about 3 years of age, many children are able to describe and rate pain, and pain scales utilizing self-report become possible and are the preferred means of assessing pain. The most commonly used is the Wong-Baker FACES© pain scale: the child points to one of six face drawings ranging from very happy (0; no pain) to very sad (5; worst pain). Similar scales include the Faces Pain Scale-Revised© (which uses a 0 to 10 scale) and the Oucher Scale© (which incorporates photographs of children instead of simple drawings and offers a variety of ethnic versions). Samples of these scales are readily available online.

Older children are able to self-report pain and can use numeric pain scales. The Verbal Numeric Scale©, also called the Numeric Rating Scale, rates pain from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain) and is validated in children aged 8 to 17 years.1 The experience of pain itself is subjective, and self-reported pain assessment is based on prior experiences and varies widely from individual to individual. Nevertheless, assigning a numeric score to pre- and post-treatment pain provides the most objective method available for assessing pain and anxiety.

ELEMENTS OF PAIN MANAGEMENT

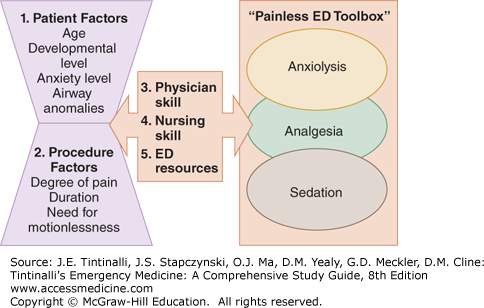

The approach to analgesia, anxiolysis, and sedation in children consists of five general elements (Figure 113-1). The variables affecting the choices and outcome of pediatric analgesia, anxiolysis, and sedation can also be thought of as four interfacing “domains”—patient, procedure, medications, and setting (Table 113-3).

| Patient Factors | Procedural Factors | Medication Factors | Setting Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

Age Weight Comorbidities Medication Allergies NPO status | Urgency Duration Requirement for emotionlessness Anxiety Pain | Route of administration Pharmacokinetics Properties (anxiolytic, hypnotic, analgesic, amnestic) Side effects | Provider skill and experience Institutional policies Resources Equipment Time constraints |

To choose the best option(s) in any given scenario, assess the child and his/her physical and psychological development, along with the procedure and its level of pain and associated anxiety, and whether the procedure requires complete stillness (such as CT with IV contrast). Synthesize these characteristics to apply the modalities available in the “tool box” (Figure 113-1).

ANXIOLYSIS

Anxiety potentiates pain, and anxiety itself is unpleasant for children and their families. Common examples of anxiety-provoking procedures are laceration repair and lumbar puncture. Although theoretically both procedures should be nearly painless, particularly with the use of topical anesthetics such as LET® (lidocaine, epinephrine, and tetracaine, for lacerations) and LMX® (liposomal lidocaine cream, applied before lumbar puncture), both the waiting period and the procedure itself can be highly anxiety provoking. Anxiety can be addressed in a variety of ways, both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic.

Parental presence (and sometimes involvement) is a fundamental technique to reduce anxiety that is both cost-free and highly effective. The form of parental presence used may vary by age of the child, but generally, for painful procedures, a well-prepared parent can “coach” the child and reduce anxiety. Allowing the parent on the stretcher with the child is particularly helpful with toddlers and school-aged children.

Distraction for younger children can take the form of picture books, stories read aloud, bubbles, light wands, songs, or music. Guided imagery and hypnosis are both effective but require specific provider training. Education and advance preparation are also useful. Procedures should be explained in a developmentally appropriate context. Child life specialists, if available, are extremely effective in reducing anxiety and acting as patient advocates.

Benzodiazepines are widely used for their anxiolytic, sedative, amnestic, and hypnotic properties. In the ED, midazolam is almost universally preferred over other agents in this class because of its relatively short duration of action. Midazolam can be given by the intranasal route, which avoids the need for IV access and affords a more rapid onset of action than the oral route. However, benzodiazepines do not have analgesic properties and should be combined with other agents if pain is also an issue. Luckily, fentanyl can also be given by the intranasal route (Table 113-4). Midazolam can cause paradoxical agitation, particularly at lower doses, and can cause respiratory depression and hypotension, particularly in hypovolemic patients. Adjunctive depressant medications can potentiate these effects.

| Drug | Concentration | IN Dose | Onset | Duration | Side Effects/Warnings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Midazolam | 5 milligrams/mL | 0.2–0.4 milligram/kg; max 10 milligrams | 5–15 min | 0.5–2 h | Excitation/paradoxical reaction Somnolence Nasal irritation Bitter taste |

| Fentanyl | 50 micrograms/mL | 2 micrograms/kg; max 100 micrograms | 5–10 min | 20–60 min | Nausea Respiratory depression (outlasts analgesic effect) Dizziness |

The main advantage of intranasal administration is a more rapid onset of action than the oral route, higher blood levels (by avoiding “first pass effects” of the GI system), and no need for IV placement. High-concentration solutions must be used because the maximum volume that can be delivered to each nostril is limited to approximately 1 mL. Because the medication particles must be within a specific size range (approximately 10 to 50 microns) to be absorbed by the nasal mucosa, commercially available (and inexpensive) “mucosal atomizer devices” are used for intranasal delivery.

Regardless of the route of administration, midazolam is more effective when dosed at the higher end of the range (e.g., 0.4 milligrams/kg for the intranasal route). Oral midazolam (which avoids the nasal irritation of intranasal administration) may be appropriately paired with topical lidocaine-epinephrine-tetracaine suspension for wound repair, as both take 20 to 30 minutes to be effective. Oral midazolam has a longer duration of effect than intranasal or IV preparations, so warn parents to protect the child from falls due to incoordination for several hours after discharge.

When IV access has already been obtained, midazolam may be used IV for anxiolysis, which has the advantage of rapid onset and is easier to titrate than other routes of administration. A lower dose (0.05 to 0.1 milligram/kg IV) is usually sufficient and should be considered, for example, in children and teens requiring lumbar puncture. Higher doses of IV midazolam can cause respiratory depression, and a few children can exhibit a paradoxical reaction to midazolam, with agitation, confusion, or crying. These reactions are self-limited and can occur with PO and intranasal administration. Both paradoxical agitation and respiratory depression may be treated with flumazenil, although this is rarely necessary.

ANALGESIA

There are a wide variety of nonpharmacologic techniques to reduce pain. Some of them, such as proper immobilization, application of ice, and elevation of fractures, may make a larger difference for the patient than medications. Although techniques such as immobilization are widely known, they are often overlooked, delayed, or omitted. Other techniques include distraction, massage, breathing techniques, acupressure, and emotional support.

Neonates must often undergo unpleasant and painful procedures, and when their pain is not addressed, it can have long-lasting effects on future response to pain. Examples of painful ED procedures include urinary catheterization, venipuncture, heel sticks, IM injections, and lumbar puncture. Oral sucrose is an effective analgesic for brief, painful procedures2 and is thought to work by activating endogenous opioids through taste receptors. It is given orally as a concentrated solution by a syringe (e.g., 2 mL of a 24% sucrose solution) or applied to a pacifier. Sucrose solution comes in a variety of commercially available formulations (such as Sweet-Ease®, a premixed 24% sucrose and water solution). Regardless of the formulation used, oral sucrose reduces physiologic measures of pain (e.g., heart rate), behavioral measures (e.g., time crying), and newborn pain scale scores.

Topical anesthetics reduce the pain of minor procedures, such as phlebotomy, Mediport access, and lumbar puncture, and are appropriate for children of all ages. Two commercially available products are EMLA® and LMX®. EMLA® (eutectic mixture of 2.5% prilocaine and 2.5% lidocaine) and LMX® (4% liposomal lidocaine) are both fat-absorbable creams that anesthetize the skin. The time to maximal effect is up to 60 minutes for EMLA® and 30 minutes for LMX®. The use of topical anesthetics may result in a delay in the time to IV access or other procedures, but it is usually appropriate to wait the additional time for the benefit of patient comfort.

LET® (lidocaine 4%, epinephrine 0.1%, and tetracaine 0.5%) is a topical anesthetic mixture for open wounds and is safe and effective for almost all laceration repairs in children. It can be applied to fingers, toes, lips, and other end-organ tissues despite the vasoconstriction effects of the epinephrine.

LET® is most effective for wounds that are not deeper than the subcutaneous tissues. LET® should be applied half into the wound and half on a saturated piece of sterile cotton (rather than gauze) at a maximum dose of 0.2 mL/kg. The adequacy of anesthesia from LET® is highly dependent on proper application technique. LET® is prepared by hospital pharmacies as a liquid, but is also available commercially as a gel. LET® should be left in place for at least 20 to 30 minutes for satisfactory wound anesthesia, with longer times (up to 45 minutes or more) generally leading to more complete anesthesia (though highly vascular tissues such as lips require less time). Blanching of the skin from the vasoconstriction effects of epinephrine is a good sign that topical anesthesia has been achieved.

Another option for topical anesthesia prior to procedures such as venipuncture and lumbar puncture is the use of a needle-free injection system. This is a highly effective alternative to EMLA® or LMX®, with the major advantage that it is nearly instantaneous.3 Needle-free injection systems deliver lidocaine into the dermis using a self-contained high-pressure delivery system such as a carbon dioxide gas cartridge. The J-tip® (National Medical Products, Irvine, CA) is currently the most widely used needle-free injection system for local anesthesia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree