Chapter 18

Pain in childhood

On completing this chapter readers will have an understanding of:

1 The prevalence of pain in infants, children and adolescents.

2 Measurement tools to assess pain in infants and children.

3 Management of paediatric pain.

4 The family as a vector for learning about pain.

5 Managing school anxiety and school avoidance due to pain.

6 The influence of sex and gender on children’s experience and learning about pain.

WHAT IS THE PROBLEM?

Children are not strangers to pain. Virtually all infants will have a heel-prick within the first few days of life to collect the few drops of blood needed for PKU and adrenal screening. Many male infants will be circumcised in the first week of life. For infants (neonates) who have health issues in their first period of life, and spend time in an intensive care unit, the risk for pain sharply increases. A recent Swiss study of ventilated newborns in the first 2 weeks of life (Cignacco et al 2009) logged 38,626 procedures in 120 preterm infants or about 23 procedures per day, per child. Three-quarters of these procedures were considered to be painful (e.g. 17–18 procedures per day per infant). In these very pain sophisticated units, almost all infants were given some form of pain comfort or analgesia. A common approach was pre-emptive oral sucrose, which has been shown to be an effective analgesic in infants (Stevens et al 2004). Oral sucrose is an example of a pain-relieving strategy that has an active physiological benefit to relieve pain in infants but no such effect in adults.

Even healthy young children are subject to a large number of needle procedures. For example, children in Canada receive about 20 needles for immunization before they turn 5 years of age. Parents may avoid or delay immunizations because of their concern about the child’s distress over the needle (Luthy et al 2009). Young children may experience other pain associated with common childhood illnesses and infections such as earache and sore throats.

As children develop their gross motor skills through play and exploration, they experience the many bumps and falls of childhood. Observational studies of such pain among preschoolers and young school-age children on a daycare playground yielded mean rates of between 0.34 and 0.41 incidents per hour per child (Fearon et al 1996; von Baeyer et al 1998). Some children experience pain from less frequent but more serious unintentional injury at home, in cars, on farms, on playgrounds, at daycare centres and at school. Injury prevention programmes are an important step in alerting adults about potential dangers to children but changing behaviours to protect children is challenging. Legislation is often needed to insure that children are sufficiently protected.

Unfortunately, many children still suffer pain and distress because their parents hit them as a form of discipline. A national study in the USA (Straus & Stewart 1999) found that 35% of parents hit infants and 94% hit children ages 3 and 4 years. Just over 50% of American parents hit children at age 12; the rate then decreased. Parents who hit their teenagers averaged doing so about six times during the year. The children most likely to be hit with an object (28%) were 5–12-year-olds. Children who are physically or sexually abused experience pain and suffering in their immediate environment. They are also at risk for chronic pain as adults (Davis et al 2005; Walsh et al 2007).

As children enter the school-age years they become more vulnerable to the commonplace and troublesome pains that also affect adults. Headache and migraine are reported by about 3–7% of school age children but increase in prevalence after puberty, particularly for girls (Unruh & Campbell 1999). 10–15% of children have recurrent abdominal pain. Recurrent abdominal pain in children is common and may be associated with irritable bowel syndrome and chronic abdominal pain in adulthood (Nurko 2009). In a recent prospective study of school-age children, 18% of children had weekly abdominal pain that persisted for more than 12 weeks (Saps et al 2009).

Four percent of school children have limb pains and 15% report growing pains (Goodenough 1998; Naish & Apley 1950). Growing pains are characterized by deep aching sensations in the muscles of the lower limbs late in the day or night. A review (Evans 2008) noted that much of the literature about growing pains is of poor quality and that no one theory has explained its aetiology. Back pain is the most common chronic pain in adults. Although typically considered to be an adult pain, back pain starts early in childhood and has a sharp incline following puberty. In a large Danish community study, 35% of 17-year-old girls and 27% of boys reported back pain in the last month (Bo Andersen et al 2006). The growing problem of childhood obesity in the Western world results in children with a greater risk of physical inactivity, deconditioning, reduced bone mineral content, poor flexibility and coordination, which increases the risk for back pain (Bo Andersen et al 2006). On the other hand, children who are competitive athletes may be at greater risk for injury-related pain that is exacerbated by denial and under-treatment of pain (Nemeth et al 2005).

The incidence and prevalence of pain in children is common throughout the Western world. For example, Huguet & Miro (2008) studied 511 9–17-year-olds in the Catalan region of Spain; 88% of children reported at least one pain episode during the previous 3 months, 38.3% visited the doctor due to the pain and 37.3% suffered chronic pain. Just over 5% had moderate or high functional disability because of pain. Perquin and colleagues (2000) reported that more than 50% of 5424 children in The Netherlands had experienced pain within the previous 3 months. Approximately one-quarter had chronic pain (recurrent or continuous pain for more than 3 months). Chronic pain increased with age and was significantly higher for girls, especially those between 12 and 14 years of age. About 9% of these children experienced frequent and intense pain. In the developing world, children’s risk for pain is increased by disease, conflict and war, poverty, malnutrition, and reduced access and availability of health care to treat pain and underlying issues (Finley & Forgeron 2006). King et al (2011) is recent meta-analysis of recurrent pain prevalence in children.

Fortunately, children are less likely than adults to develop serious acute or chronic health conditions that are also associated with pain. Nevertheless, some children do have cancer, HIV/AIDS, neurodegenerative disorders or rapidly progressive forms of cystic fibrosis (Berde & Collins 1999). Children with cancer experience pain due to the growth of tumours and from the procedures used to diagnose and treat their disease. Long-term survivors of childhood cancer may have causalagia, phantom limb pain, postherpatic neuralgia and central pain even though the cancer appears to be cured (Berde & Collins 1999). Neurological degeneration associated with HIV/AIDS may be painful and, as with cancer, the procedures to diagnose and treat this disease may be painful (Hirshfield et al 1996). Headache and chest pain are common in children with cystic fibrosis, especially in the last 6 months of life or if the disease has a rapid progress (Berde & Collins 1999). Sickle cell disease is an inherited blood disorder diagnosed by newborn screening. It is a chronically painful disease with both pain crises and chronic pain (Brousseau et al 2009).

The most common childhood disease that is accompanied by pain is juvenile chronic arthritis (JCA). The prevalence of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis in the community when diagnosed by clinical examination may be as high as 4 in 1000 (Manners & Diepeveen 1996). In the USA, approximately 294,000 children are diagnosed annually with significant paediatric arthritis and other rheumatologic conditions (Sacks et al 2007). Approximately 25% of children with JCA have moderate to severe pain due to the disease (Schanberg et al 1997).

Fibromyalgia is a common chronic pain syndrome in adults marked by widespread non-joint musculoskeletal pain and generalized tender points. This syndrome also affects children, especially teenage girls. Some clinicians and researchers prefer to refer to fibromyalgia as widespread pain. Buskila (2009a,b) has reviewed the research on fibromyalgia and found that in addition to pain, fatigue, non-restorative sleep, difficulties in thinking, irritable bowel syndrome, chronic fatigue, chronic headache and depression often accompany fibromyalgia. Central nervous system sensitization is a major pathophysiologic aspect of fibromyalgia. Trauma and stress often trigger its development. Treatments for fibromyalgia in children include mild to moderate exercise, antidepressants, and antiepileptics and cognitive–behavioural interventions. The outcome for children with fibromyalgia appears more positive than the outcome for adults.

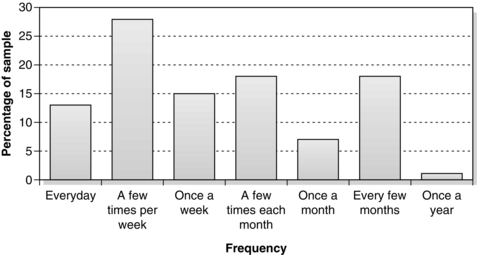

Atypically developing children are probably at higher risk for pain due to underlying issues affecting their development. Clancy et al (2005) surveyed 68 children with spina bifida (30 males, 38 females) between the ages of 8 and 19 years of normal intelligence. Figure 18.1 presents the frequency of pain they reported. She found that 56% of children with spina bifida had pain once a week or more. About one in eight had pain every day.

Fig. 18.1 Frequency of pain in children with spina bifida. Reprinted from Clancy C A, McGrath P J, Oddson B E 2007 Pain in children and adolescents with spina bifida. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 47:27–34, with permission from John Wiley & Sons.

Similarly, pain is more common in children with developmental delays. McGrath et al (1998) showed that parents and caregivers used behaviours to identify pain in children with cognitive impairments and delays. Using a validated behavioural report by parents (Breau et al 2000), Breau and her colleagues (Breau et al 2003), in a cohort study of 94 children with severe to profound cognitive delay aged 3 to 18 years, found that 73 children (78%) experienced pain at least once in a 4-week period. Accidental, gastrointestinal, infection and musculoskeletal pain were the most common. Children had an average of 9 hours per week of pain. In a subsequent study, Breau et al (2007) reported that in a year when children had more pain, they also had much poorer cognitive and social development, suggesting that pain interferes with development in these children. Such pain has significant impact on quality of life for these children (Oddson et al 2006).

Often the disease or underlying injury is itself painful for the child, but the procedures to treat the problem may also inflict pain. Debridement of dead tissue, hydrotherapy and dressing changes are painful procedures for children recovering from burn injuries. Splinting and range of motion exercises and activities can be painful for children who are recovering the use of a limb from a position of immobility. Lumbar punctures, bone marrow aspirations, injections, heel lances and so on can be painful if not adequately managed. Circumcision, a common procedure for male infants, usually performed for non-medical reasons, is painful if performed without analgesia (Geyer et al 2002).

WHAT ARE THE CHALLENGES?

Developmental considerations

The central and peripheral system is immature in early life but the basic connections in nociceptive and pain pathways are formed before birth (Fitzgerald 2005). There are also important postnatal changes that affect pain sensitivity and perception. The infant does not appear to have the segmental control mechanisms within the spinal cord or the descending controls from the cortex that are present in an adult (Fitzgerald 2005). Because of this neurological immaturity, an infant will have very little, if any, ability to dampen down a pain stimulus using cortical mechanisms. The implication is that infants may be extremely sensitive to all stimuli and may have heightened pain sensitivity and arousal.

Early pain events in infancy and childhood can have an impact on later pain experiences in at least two ways. The first is through memory and learning. Although it is obvious that at some point in our life we remember and learn from negative painful experiences, it is not clear when such learning begins to occur. It is part of neonatal intensive care unit folklore that infants who are subjected to numerous invasive procedures soon develop the tendency to ‘go off’ when their incubator is approached by anyone (McGrath & Unruh 1993). These babies demonstrate anticipatory anxiety behaviour.

Infants are also capable of developing a physiological memory of pain. In a series of studies, Taddio and colleagues found that male infants who were circumcised had higher pain scores at their routine 4- and 6-month immunizations than male infants who were not circumcised (Taddio et al 1995, 1997). Further, infants who were given EMLA, a local anaesthetic, had lower pain scores at immunizations than infants who were circumcised with a placebo. Taddio (1999) argued that circumcision may produce long-lasting changes in infant pain behaviour because of changes to the infant’s central nervous system processing of painful stimuli.

Unfortunately, the belief that infants and children do not remember pain, or if they do remember it, then the memory is not long-lasting, has contributed to the inadequate management of children’s pain (Cunningham 1993). Aversive childhood pain experiences can have long-term negative consequences even in adulthood, leading to fears of procedures, health professionals and healthcare settings. Such fear and anxiety can have devastating consequences for children who have chronic health conditions and recurrent or chronic pain.

Sex and gender have an impact on the pain experience of adults and the roots of this influence probably begin in childhood. There is little evidence that the sex of a child affects the prevalence of pain until puberty. After puberty, the prevalence of headache, migraine and abdominal pain increases for girls (Unruh & Campbell 1999). On the other hand, gender may have an important impact on pain through socialization and cultural expectations about pain and gender roles. There is some evidence that boys in particular are socialized to be more stoic in response to pain as part of social expectations about masculinity. Evans et al (2008) found that there was an association between girls’ (not boys’) complaints of pain and responses to experimental pain with the pain reports of their mothers. Moon et al (2008) reported that fathers were better judges of pain in their children than mothers.