PAIN: HEADACHE

CHRISTOPHER KING, MD, FACEP AND DENIS R. PAUZé, MD, FACEP

Headache is a common complaint of pediatric patients in the emergency department (ED). It is estimated that by the age of 15 years, up to 75% of children have experienced headaches, although most are cared for at home. Headache as an isolated complaint is a relatively unusual presentation in pediatric patients; it is more often one of a number of symptoms, such as fever, lethargy, sore throat, neck pain, and vomiting.

Like other challenging presentations, headache is seen with regularity and is often benign, but in a small subset of patients, it can portend a potentially life-threatening illness. Therefore, the primary responsibility of the emergency physician is to make the important discrimination between “bad” headaches and benign headaches. Fortunately, this differentiation can almost always be done successfully after a thorough history and physical examination, and when necessary, laboratory and radiographic tests. One notable exception to this rule, however, is brain tumor. Although most serious illnesses that cause headache (e.g., meningitis, encephalitis, ruptured vascular anomaly) will be readily classified in the “bad” category, the presence of a brain tumor may not be. The history can be subtle, and the examination is commonly unrevealing, often leading to a delay in diagnosis. Therefore, characteristics of headaches caused by a brain tumor are described in detail in this chapter. Above all, the key to proper management of such patients is ensuring appropriate follow-up care.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

For a headache to occur, there must be a noxious stimulus that affects one or more pain-sensitive structures. Injury to an area that is insensitive to pain, such as nonhemorrhagic stroke, may cause significant morbidity but will not manifest as headache. It is therefore useful to consider the sensory innervation of the head and neck. All extracranial structures are sensitive to pain. Thus, processes that affect the sinuses, oropharynx, scalp, or neck musculature often cause patients to complain of headache. In contrast, certain intracranial structures are sensitive to pain and others are not. For example, the brain, ependymal lining, choroid plexus, and much of the dura and pia-arachnoid over the hemispheres are insensitive to pain. Pathologic processes affecting these areas can cause headache, but only by impinging on adjacent pain-sensitive structures. The most pain-sensitive intracranial structures are the proximal portions of the large cerebral arteries at the base of the brain, the venous sinuses, and the large cerebral veins.

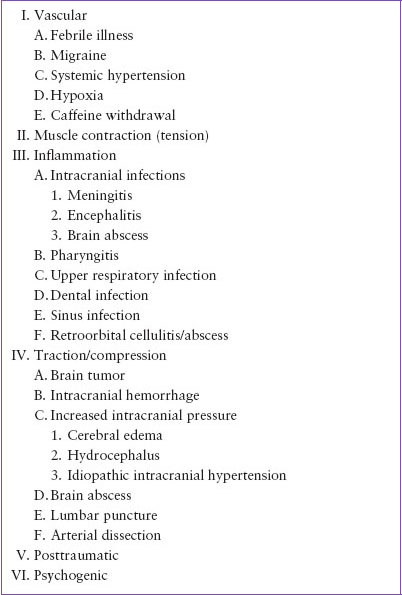

Various physiologic mechanisms come into play in causing headache. Painful stimuli can be broadly categorized as resulting from vascular effects, muscle contraction, inflammation, and traction/compression (Table 54.1). Examples of each of these types of headache etiology are described in the following discussion of differential diagnosis. It should be noted that visual problems are an unlikely cause of significant headaches in children. A child with persistent headaches that have previously been attributed to “eye strain” may, therefore, deserve a more careful evaluation.

Attempting to predict the neuroanatomic location of a pathologic process using only the site of headache described by a child is unreliable. In part, this is attributable to the unpredictable displacement of structures caused by a mass lesion. In addition, the extremely complex relationships of the various nerves involved in pain sensation of the head and neck lead to unexpected patterns of referred pain. Thus, a posterior fossa lesion can cause frontal or orbital pain, and supratentorial lesions may result in pain localized to the occiput or the back of the neck, for example.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

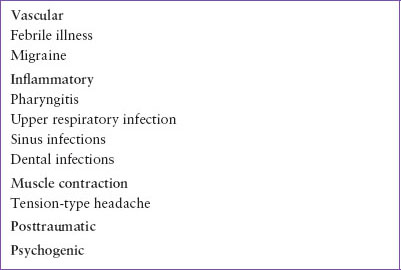

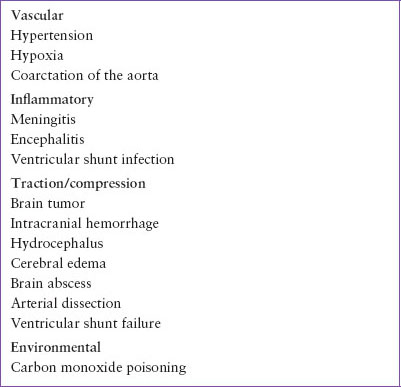

A comprehensive discussion of the various causes of headache in pediatric patients is beyond the scope of this textbook. The conditions described here are those most likely to be seen in acute- and emergency-care settings (Table 54.2) and those with the greatest potential for imminent morbidity or mortality (Table 54.3). Fortunately, the majority of pediatric patients who present to the ED with headache have a benign condition. In a study of 432 children and teenagers evaluated in the ED for headache, Conicella et al. found that the most common etiologies were upper respiratory infection (19%), migraine (18.5%), posttraumatic headache (5.5%), and tension-type headache (4.6%). Anatomic abnormality (e.g., Chiari malformation), brain tumor, meningitis, idiopathic intracranial hypertension, and ventricular shunt failure were found in a total of 6% of patients.

Vascular

Headaches associated with vascular changes are believed to be caused primarily by vasodilation, although the exact mechanism has yet to be fully elucidated. One common example of this type of headache is migraine. Migraine headaches are typically chronic and remitting, with a characteristic pattern that is easily described by the patient or parents (see Chapter 105 Neurologic Emergencies). Often, a strong family history of migraines is present. For the emergency physician, the main issue with migraine patients is generally pain control, because the diagnosis is already known. However, a significant change in the quality, severity, or timing of headaches in these patients may represent a separate and potentially more serious problem. In such cases, the clinician should not be dissuaded by the existing diagnosis from pursuing an appropriate workup as indicated.

Headaches accompanying fever are also believed to be mediated by vascular effects. Because fever is such a common symptom, this is probably the most common cause of headaches in pediatric patients seen in the ED. Hypertension, although rare, is another possible cause of vascular headaches in children. Renovascular disease leading to hypertension can in some instances be a life-threatening etiology. Additionally, children and teenagers may have an undiagnosed coarctation of the aorta leading to hypertension and associated headaches. Because of its rarity, this condition is easily misdiagnosed. Hypertension causes not only global changes in cerebral vasculature, but also possibly a component of increased intracranial pressure (ICP) that leads to headache.

TABLE 54.1

PATHOPHYSIOLOGIC CLASSIFICATION OF HEADACHES

TABLE 54.2

COMMON CAUSES OF HEADACHE

TABLE 54.3

LIFE-THREATENING CAUSES OF HEADACHE

Finally, hypoxia is a potent stimulus for cerebral vasodilation and can produce headaches on that basis. Therefore, children who experience a hypoxic insult (e.g., carbon monoxide poisoning) or those with disease states that predispose to hypoxia (e.g., cystic fibrosis, cyanotic heart disease) may present with headaches resulting from an acute process or an exacerbation of an underlying illness.

Muscle Contraction

Headaches can be caused by contraction of the scalp or neck muscles. This is the classic “tension” headache that is common in adults. These headaches usually occur when a patient has experienced prolonged mental or emotional stress or desk work with inadequate attention to ergonomic factors. This leads to recurrent episodes of muscle tension and/or spasm, which cause muscle soreness. The patient can often localize a specific site where the pain is felt, and the involved muscles may be tender to palpation. Although muscle contraction is an unlikely cause of headache in younger children, the stress of life during adolescence will often produce this type of headache. Onset is typically at the end of the day. A headache that is present on arising in the morning or that awakens a patient from sleep is an unusual manifestation of muscle contraction.

Inflammation

A wide variety of inflammatory conditions can result in headache, ranging from benign to potentially life-threatening entities. Children with bacterial meningitis or encephalitis may present with headache, although this is usually only one of a constellation of symptoms, such as fever, lethargy, neck pain, confusion, or coma. Headache is unlikely to be the sole complaint in these patients. However, an older child or adolescent with viral meningitis can present with a severe headache, mild, or sometimes no neck discomfort and no other signs of significant illness. Fortunately, viral meningitis is generally a benign process. Rare causes of inflammatory headache include retroorbital cellulitis or abscess and brain abscess. Focal findings on neurologic and/or ocular examination will normally provide clues to these unusual diagnoses.

Headaches can also be caused by inflammatory processes affecting other structures of the head and neck. For example, pediatric patients with pharyngitis caused by group A streptococcus will often complain of headaches. Indeed, the classic presentation for streptococcal pharyngitis in children is sore throat, fever, and headache, sometimes associated with abdominal pain. In a child who has difficulty localizing pain, otitis media and otitis externa can also present as headache. Pediatric patients with sinusitis will sometimes complain of facial or periorbital pain, although younger children may simply have a persistent nasal discharge. Dental abscess can be overlooked as a cause of headache because it is a relatively uncommon finding in children. Therefore, a careful examination of the teeth and gingiva should be performed for all pediatric patients with unexplained headaches. Finally, inflammation of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is a rare cause of unilateral headaches in children (TMJ syndrome). These patients typically report increased pain while chewing and have point tenderness over the mandibular condyle.

Traction/Compression

Headaches can be caused by mass effect from a pathologic lesion that produces traction and/or compression involving pain-sensitive structures of the head and neck. For the emergency physician, the most important conditions in this category are intracranial hemorrhage and brain tumor. An intracranial hemorrhage produces displacement of surrounding tissues and, in cases of more significant bleeding, increased ICP. In the pediatric population, this is most often the result of a severe head injury (see Chapter 121 Neurotrauma). However, in rare instances, a child can have a nontraumatic intracranial hemorrhage from a ruptured vascular anomaly (e.g., an arteriovenous malformation), which leads to bleeding into the brain parenchyma and ventricles. As with other vascular events, this type of hemorrhage is characterized by the abrupt onset of severe pain. In contrast, headaches resulting from a brain tumor typically have a more insidious onset. The child will often complain of progressively worsening headaches for several weeks or months. Additional symptoms, such as persistent vomiting or gait abnormalities, may also be present. Unfortunately, the physical examination can be normal during the early phase of the illness, and as mentioned previously, this commonly leads to a delayed diagnosis. Other processes that cause headache as a result of traction and compression include idiopathic intracranial hypertension, brain abscess, hydrocephalus, ventricular shunt failure, and persistent spinal fluid leak after lumbar puncture.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree