Chapter 17

Pain education for professionals

By the end of this chapter readers will be able to:

• Assess their current learning needs around pain management and identify effective learning strategies.

• Discuss the skills needed and opportunities for interprofessional learning and working in pain management.

• Outline the issues and opportunities in undergraduate, postgraduate and in-service pain education.

• Describe the need for continuing professional development and opportunities for further study.

OVERVIEW

In 2010, the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP; International Association for the Study of Pain 2010) launched the Declaration of Montreal, an important statement highlighting the fundamental human right to an appropriate assessment by healthcare professionals, access to pain relief and specialist referral where relevant. A major knowledge deficit in healthcare professionals was one of the reasons IASP gave for inadequate pain management worldwide. Education can be a powerful solution to addressing gaps in knowledge, but having an understanding of pain is only part of the picture. Providing patients with effective pain management also requires a range of skills, understanding our own attitudes, limitations and insight into our own learning needs. This chapter focuses on the education of healthcare professionals, helping readers to refine their skills for supporting patients in pain, discusses collaborative learning and working, highlights important issues for undergraduates and postgraduates, and signposts readers to further educational resources. The chapter is aimed at both learners and those delivering pain education to professionals.

BUILDING A KNOWLEDGE BASE AND IDENTIFYING KEY SKILLS

Identifying specific learning needs involves assessing your current strengths in managing pain and identifying priority areas for development. An interesting starting point is to evaluate attitudes and feelings around pain which can have a significant impact on the way we interact and support others. Spend a few minutes considering the points in Box 17.1, which should lead you to think about your own attitudes and may challenge existing thinking.

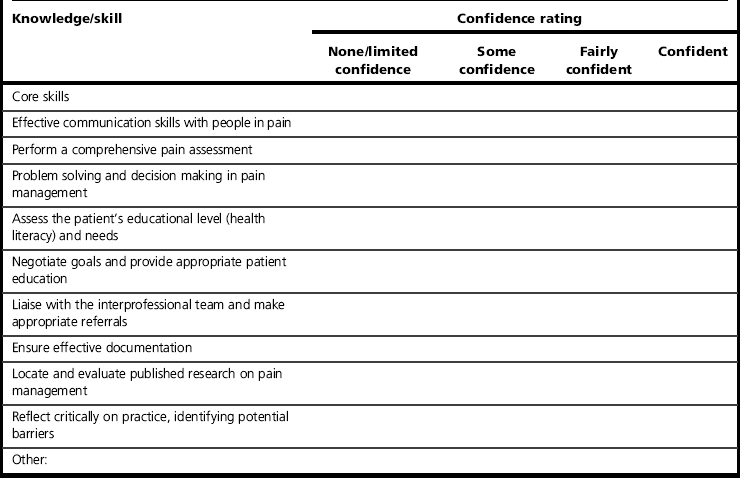

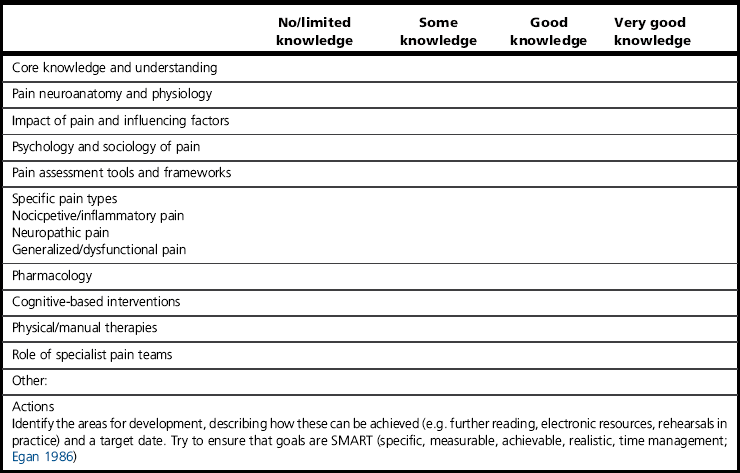

Learning pain management skills and knowledge is more effective if the starting point is acknowledged and people identify their current learning needs. Table 17.1 presents a skills profile with some key pain management areas to start thinking about strengths and areas for development. Writing goals can help to identify the next steps, taking into account the educational resources you have access to.

Once you have identified your learning needs and have a specific plan, you may want to access independent learning resources on pain management. Table 17.2 highlights a few of the available resources.

Table 17.2

Resources for independent learning about pain

| Resource | Examples |

| Books | An enormous range of books is available, including general introductory texts, condition-specific and patient education books. These can be accessed through public, NHS and university libraries |

| Journals | British Journal of Pain European Journal of Pain Journal of Pain and Symptom Management Pain |

| Websites of professional organizations | British Pain Society, International Association for the Study of Pain |

| Pain-related charities | |

| general | Pain UK |

| condition specific | Pelvic Pain Support Network, Pain Community Centre website |

| Online videos or lectures publically available | SlideShare, Henry Stewart Lectures Series |

| Lectures series that require an institutional subscription | British Pain Society publications |

| National guidelines | National Institute for Heath & Clinical Excellence, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network |

Learning experiences and strategies

We all have experienced successful learning moments where we were inspired, motivated to learn and there is a positive outcome. A number of factors may have contributed to this situation (an interesting topic, an inspirational teacher) but one tool that can accelerate learning in pain management is metacognition. Metacognition is often referred to as ‘learning about learning’ or ‘knowing about knowing’ (Postholm 2011) and it describes the knowledge of your preferred approach to learning and skills in choosing a learning technique in a given situation. For example, Philippe is a year 3 undergraduate who has met a patient on placement with complex regional pain syndrome, a condition he wants to learn more about. Philippe is aware that his learning is most effective when there are visual and auditory stimuli so plans his learning accordingly, choosing to access an online video first. He later supplements this with written material and presents the patient as case study to his peers as a way of evaluating his own understanding and sharing his learning. Study skills textbooks can provide valuable resources and information to refine your metacognitive skills, provide useful tools to assess learning styles and preferences as well as advice on maximizing learning from different experiences such as lectures, group work etc. (e.g. Burns & Sinfield 2008; Cottrell 2008).

Making the most of lectures

Whether you are attending a study day, seminar or a formal programme of study, lectures will form a key part of pain management education. Preparation and using key techniques during and after the lecture can make the learning much deeper. Beforehand, read through any previous lecture notes and key texts to get a sense of the topic and the key terms. Write down any terms that are unclear and questions you would like to ask, leaving space for the answers (Cottrell 2008). Suggestions for making notes more meaningful include:

• Use key headings and list the points – avoid writing everything down. Details can be obtained later from a textbook and this will help you listen.

• Try to actively make connections with existing knowledge and ask questions (Is this always the case? Do I agree?).

• Consider using the pattern note-making system (similar to mind maps; see Burns & Sinfield 2008 for details) where you identify keywords and link them together to create a visual representation of the topic. This is an active learning strategy that promotes the connections of ideas and concepts.

• As soon as possible after the lecture, read through lecture notes and add any additional detail from other sources and discuss the ideas explored with other people (Burns & Sinfield 2008; Cottrell 2008).

Group work

Group works offers an opportunity for collaborative learning, shared workload and responsibility and social support (Burns & Sinfield 2008; Cottrell 2008). Interpersonal skills and techniques such as negotiation, giving and receiving feedback, problem solving and summarizing arguments are skills that can be rehearsed and refined. Any aspect of interprofessional learning (two or more professions learning and working together) will involve group work, reflecting the skills needed for pain management practice.

• understand the task required

• brainstorm, make notes and plan how the end goal will be reached

• follow the agreed action plan

• offer positive and constructive feedback

• review findings and leave time to proof-read and practice presentations (Burns & Sinfield 2008).

Early on in group work, it is useful to establish the ground rules, decide how you will communicate outside of meetings (e.g. email, web discussion board, social networking site) and identify key roles to assist the team to engage and successfully complete the activity or assignment. These may include group chair, note-taker and coordinator for completed tasks. Ensure that the workload is evenly spread and everyone has a chance to contribute. Regularly review the group’s progress: How supportive are the group? Do one or two people dominate the discussion? Could the discussion have been organized differently? How well did you contribute? Always aim to be a supportive, critical friend who is ‘a trusted person who asks provocative questions, provides data to be examined through another lens, and offers critiques of a person’s work as a friend. A critical friend takes the time to fully understand the context of the work presented and the outcomes that the person or group is working towards. The friend is an advocate for the success of that work. (Costa & Kallick 1993, p. 49)

E-learning

• using a virtual learning environment (a web-based programme for resources, discussions and assessments)

• downloadable lecture notes, podcasts and presentations

• e-communications – email, live chat (synchronous discussion in real time), discussion boards (asynchronous discussion)

• use of web cams and video links

• simulation and interactive materials

• activities such as wikis (a website that allows collaborative working, contributions and editing) and blogs (an online discussion thread by an individual or group) or creating an e-portfolio

E-learning is an active learning process that may be challenging, especially if unfamiliar systems and new activities are used. Approach these new experiences with an open mind and willingness to learn about how to learn in this new way as well as taking away new pain-management knowledge and skills. One of the great benefits of e-learning is an ability to personalize your learning around pain based on identified needs or your skills profile. For example, in the classroom, an introductory session on pain physiology can be revisited for revision but then further resources may help people apply this to new knowledge to areas such the neurophysiology of pain in children. Try to treat e-learning on pain in the same was as other learning methods: create a physical or electronic file, gathering resources and making notes. If e-learning is new to you, Cottrell (2008) provides a good chapter on making learning more effective.

UNDERGRADUATE EDUCATION

The amount of pain education in undergraduate programmes for healthcare professions varies enormously. A UK survey of 19 universities (108 undergraduate programmes) revealed that students had between 2 and 158 hours on pain management although the average was just 12 hours (Briggs et al 2011). Some programmes offered separate pain modules (n = 11, 14.8%), although most of these were optional rather than core to all students. The predominant learning strategies used were lectures (n = 65, 87.8%) and case studies (n = , 78.4%) with around a third using e-learning resources. How learning is encouraged can make a difference. All learning strategies have their strengths and weaknesses, but lectures in particular have been criticized as promoting a passive rather than active learning experience, encouraging surface learning (knowledge recall) rather than deep learning (engaging, problem solving, making connections between ideas) and does not help people apply or analyse new knowledge (Light et al 2009; Ramsden 2003). As we have seen earlier, healthcare professionals involved in pain management need a range of skills, knowledge and education needs to encourage this development. Learners, clinicians and academics can all do something to improve the learning experience around pain.

Learners on undergraduate programmes

The curriculum will involve a broad range of topics and conditions, and pain will feature in many cases. Try to consider the pain-related issues in every situation, reflecting on the impact it has on people and the management of their condition. Think about the professionals that may be involved in their care and their role in that situation. For example, the topic of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) could be studied in terms of the virology, diagnosis, impact and recommended treatment and care. However, up to 69.4% will experience painful HIV-related neuropathy (Ghosh et al 2012) and this will need to be explored and understood along with an insight into the role of the interprofessional team.

Academics and clinicians promoting pain education

Introducing changes to the curriculum can present a number of challenges and it is important to identify and try to predict the issues so that they can hopefully be addressed. Gibbins et al (2009) interviewed curriculum coordinators in 50% of UK medical schools to explore the factors that help or hinder the introduction of palliative care into their programmes. The themes that emerged are familiar issues and transferable to the topic of pain. These have been used as a basis for the recommendations in Box 17.2, which contains suggestions for supporting change.

The strategy should involve identifying the key stakeholders, including students, academics, curriculum leads and clinical partners. Reviewing existing teaching and learning strategies and content, and building a case (one that keeps the patient experience and the importance of pain management at the centre of the argument) can be helpful. Box 17.2 also contains some useful documents with statistics that can assist in building this case. Patient/user groups can also be strong advocates for change and can advise on curriculum content as well as contributing to the actual delivery of sessions, thus having a powerful impact on learners (see Terry 2012 for example).

INTERPROFESSIONAL LEARNING AND WORKING

The World Health Organization (2010) highlighted the need for a collaborative, practice-ready work force, professionals who have learned to work together in order to provide better services for patients and improve health outcomes. Pain management is an interprofessional activity and requires understanding of each other’s roles and close collaboration to provide effective management. Interprofessional education (IPE) has key role to play in this and the Centre for Advancement of Interprofessional Education (Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education 2002) considers IPE as occurring in work-based or academic settings ‘when two or more professions learn with, from and about each other to improve collaboration and the quality of care’.

• focus on the needs of individuals, families and communities to improve their quality of care, health outcomes and well-being

• apply equal opportunities within and between the professions and all with whom they learn and work

• respect individuality, difference and diversity within and between the professions and all with whom they learn and work

• sustain the identity and expertise of each profession

• promote parity between professions in the learning environment

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree