PAIN: DYSPHAGIA

RAHUL KAILA, MD, RONALD A. FURNIVAL, MD, AND GEORGE A. WOODWARD, MD, MBA

The primary function of swallowing is the ingestion, preparation, and transport of nutrients to the digestive tract. Secondary functions of swallowing are the control of secretions, clearance of respiratory contaminants, protection of the upper airway, and equalization of pressure across the tympanic membrane through the eustachian tube. Dysphagia is defined as any difficulty or abnormality of swallowing. Dysphagia is not a specific disease entity but is a symptom of other, often clinically occult, conditions and may be life-threatening if respiration or nutrition is compromised. Odynophagia (pain on swallowing) or sialorrhea (drooling) may also be present in the dysphagic pediatric patient. Globus pharyngeus refers to the feeling of a lump in the throat. This chapter briefly presents the normal anatomy and physiology of swallowing, the differential diagnosis of disturbances of this process, and the evaluation and treatment of the pediatric patient with dysphagia.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Swallowing begins in utero as early as the 10th to 14th week of gestation, playing an important role in gastrointestinal development and regulation of amniotic fluid volume. By the 34th week of gestation, this complex process, involving 26 muscles, 6 cranial nerves (V, VII, IX, X, XI, and XII), and cervical nerves C1 to C3, is functional, although incompletely coordinated with breathing. In the first few days after birth, each infant develops an individual pattern of sucking, swallowing, and breathing, usually with a 1:1 or 1:2 ratio of breaths per suckle, to prevent aspiration of material into the larynx. This stage of suckling, or suckle feeding, is primarily under medullary control, with minimal input from the cerebral cortex. A transitional period begins at 6 months of age, as the cortex gradually exerts more control over the pre-esophageal phase of swallowing, allowing for the introduction of solid foods. Swallowing in the esophageal region remains an autonomic process, with vagal sensorimotor control coordinating peristalsis of the upper striated and lower smooth muscle of the esophagus. By 3 years of age, the swallowing pattern is mature, although the pediatric patient, unlike the adult, may regress to a less mature stage if normal swallowing is disrupted.

To facilitate suckle feeding and breathing, the infant oropharynx is anatomically different from the adult, with a relatively larger tongue, smaller oral cavity, and more anterior and superior epiglottis and larynx. As the face and mandible grow, the oropharynx enlarges, creating more room for the eventual voluntary use of the tongue and dentition, and the larynx descends, eventually allowing for mouth breathing. Although breathing continues to cease during swallows, the older child depends less on close coordination between eating and breathing.

A normal swallow, using the suckling infant as an example, begins with rhythmic movement of the lips, tongue, and mandible. These parts function as a unit, creating negative intraoral pressure, while also compressing the nipple. The milk expressed from each suckle is stored in the posterior oral cavity until a larger fluid bolus is formed. As the tongue delivers the bolus to the pharynx, the nasopharynx is closed off by the posterior tongue and by elevation of the soft palate. The larynx elevates to a position under the tongue, closing the airway, as the epiglottis inclines to direct the bolus posterior. A pharyngeal wave of contraction sweeps the bolus toward the upper esophagus, where the cricopharyngeal sphincter relaxes, allowing passage into the esophagus. As the esophagus begins peristaltic contractions and the bolus moves past a relaxed lower esophageal sphincter into the stomach, the airway reopens, the cricopharyngeal sphincter constricts to close the upper esophagus, and respirations resume. Dysphagia can result from disruption of normal mechanisms at any stage of the swallowing process.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

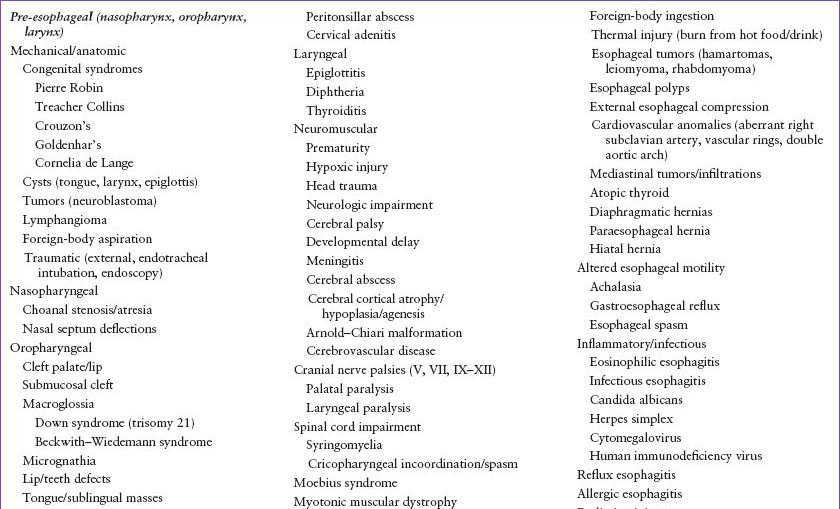

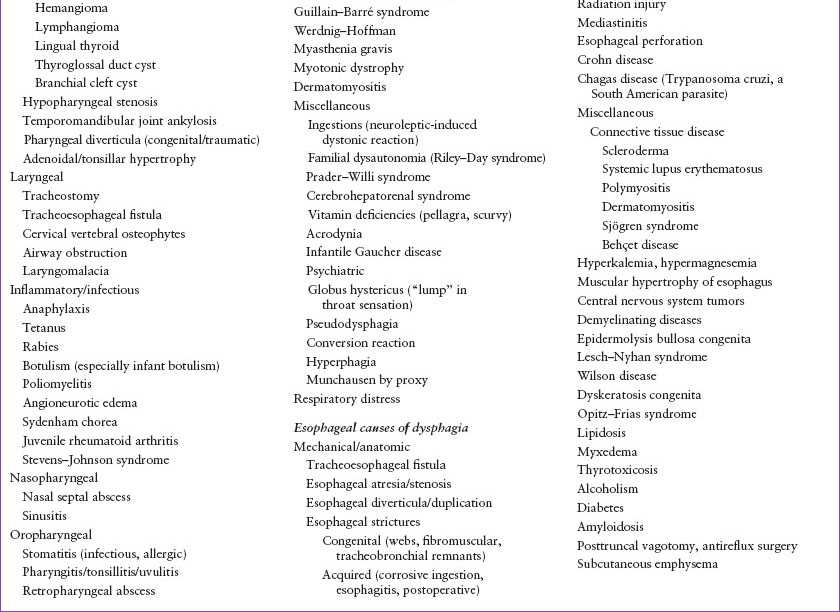

Acute dysphagia is one of the urgent symptoms needing immediate evaluation. While this may be an acute symptom in a healthy child, it may be a new or recurrent symptom in the increasing number of children surviving with chronic conditions. The incidence and prevalence of pediatric dysphagia is increasing, probably due to improved early medical and supportive care for prematurity and other conditions. The differential diagnosis for dysphagia is extensive and is commonly divided into pre-esophageal or esophageal disorders (Table 51.1). Pre-esophageal causes of dysphagia are further subdivided into anatomic categories, including nasopharyngeal, oropharyngeal, laryngeal, and generalized problems. Infectious and inflammatory disorders of either anatomic region may disrupt swallowing, whereas neuromuscular problems tend to be predominantly pre-esophageal, given the autonomic function of the esophagus. However, the esophagus can be affected by motility disorders intrinsic to smooth muscle. Finally, the differential diagnosis includes several systemic conditions that may affect the normal swallowing process. In a large case series of pediatric patients who underwent fiberoptic evaluation of swallowing function after presenting with dysphagia, 36% were found to have structural abnormalities of the aerodigestive tract or airway, 26% had neurologic diagnoses, 12% had gastrointestinal disorders, 8% had genetic syndromes, 5% had prematurity, 3% had cardiovascular anomalies, and 2% had metabolic issues.

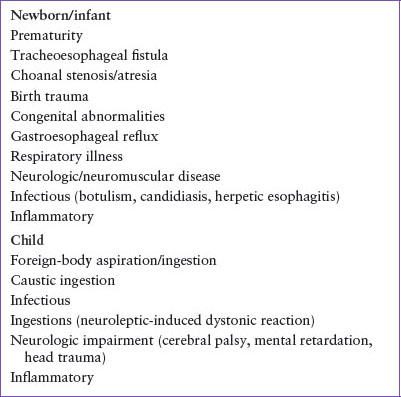

In the adult patient, dysphagia most commonly results from a variety of neuromuscular disorders, whereas the pediatric patient more often has swallowing difficulty from congenital, infectious, inflammatory, or obstructive causes (Table 51.2). Dysphagia occurs in 85% of cerebral palsy patients, and is directly related to the severity of their overall neuromuscular impairment. In the newborn or infant, swallowing may be disturbed as a result of prematurity, often associated with respiratory and neurologic disabilities. Gastroesophageal reflux is common in infants, although in a small percentage of patients, it may persist into childhood with reflux esophagitis. Eosinophilic esophagitis has recently been identified as an important cause of dysphagia, particularly in adolescents and young adults with environmental allergies, atopy, and food allergies. Ingestion or aspiration of a foreign body must always be considered in an infant or toddler who has either the acute or chronic onset of dysphagia (Fig. 51.1). Swallowing dysfunction is a common complication following pediatric head injury. In a review of 1,145 pediatric head injury patients, 68% of those with severe injury and 15% of those suffering moderate injury were found to have dysphagia requiring intervention. Postoperative dysphagia is also common after laryngotracheal reconstruction surgery or cardiovascular surgery. In a review of 2,255 children who had cardiovascular surgery, Sachdeva et al. found that 1.7% had vocal cord dysfunction associated with significant feeding problems and required prolonged gastrostomy feeding. These patients are predisposed to aspiration due to impaired airway protection.

TABLE 51.1

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF DYSPHAGIA

TABLE 51.2

COMMON CAUSES OF DYSPHAGIA

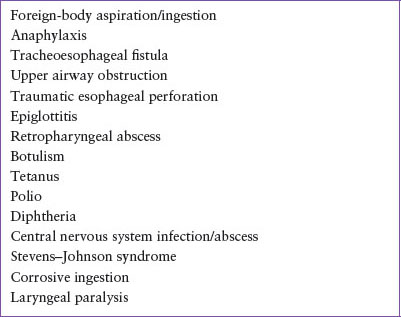

TABLE 51.3

LIFE-THREATENING CAUSES OF DYSPHAGIA

Life-threatening causes of dysphagia may involve airway compromise, serious local or systemic infection, and inflammatory disease (Table 51.3)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree