Pain and Sedation Management

Sapna R. Kudchadkar

R. Blaine Easley

Kenneth M. Brady

Myron Yaster

We must all die. But that I can save (a person) from days of torture, that is what I feel as my great and ever new privilege. Pain is a more terrible lord of mankind than even death itself.

Albert Schweitzer

KEY POINTS

The PICU poses unique challenges for pain and sedation management. Hospitalization in general, and admission to the PICU in particular, are frightening and painful experiences to children and their families.

The PICU poses unique challenges for pain and sedation management. Hospitalization in general, and admission to the PICU in particular, are frightening and painful experiences to children and their families. The goals of pain and sedation management in the PICU are to provide a child with anxiolysis and comfort while maintaining safety, promoting sleep, and preventing delirium.

The goals of pain and sedation management in the PICU are to provide a child with anxiolysis and comfort while maintaining safety, promoting sleep, and preventing delirium. Infants and children may be unable to describe their pain or their subjective experiences. Pain assessment and management are interdependent, and it is important to delineate accurate data about the location and intensity of pain, as well as the effectiveness of measures used to alleviate or abolish it.

Infants and children may be unable to describe their pain or their subjective experiences. Pain assessment and management are interdependent, and it is important to delineate accurate data about the location and intensity of pain, as well as the effectiveness of measures used to alleviate or abolish it. Optimal sedation management involves measuring a child’s level of sedation at regular intervals and to use these measures to avoid oversedation or undersedation as both have the potential to produce morbidity and mortality.

Optimal sedation management involves measuring a child’s level of sedation at regular intervals and to use these measures to avoid oversedation or undersedation as both have the potential to produce morbidity and mortality. Given the complex team framework of staff who provide and manage sedation, the use of a streamlined sedation assessment tool is necessary to facilitate consistent communication and optimal therapy. The most commonly used sedation assessment tools are the State Behavioral Scale and the COMFORT Scale.

Given the complex team framework of staff who provide and manage sedation, the use of a streamlined sedation assessment tool is necessary to facilitate consistent communication and optimal therapy. The most commonly used sedation assessment tools are the State Behavioral Scale and the COMFORT Scale. Very few studies have evaluated the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of analgesic and sedative drugs in critically ill patients. Most of the recommendations in this chapter are based on experience and best practice, rather than evidence-based medicine.

Very few studies have evaluated the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of analgesic and sedative drugs in critically ill patients. Most of the recommendations in this chapter are based on experience and best practice, rather than evidence-based medicine. Opioids bind G-protein-coupled receptors and regulate transmembrane signaling. The most commonly used opioids in pain management are µ agonists, which include morphine, meperidine, methadone, codeine, oxycodone, and the fentanyls. All of the µ-opioid agonists have similar pharmacodynamic effects at equianalgesic doses, including analgesia, respiratory depression, sedation, nausea and vomiting, pruritus, constipation, miosis, tolerance, and physical dependence.

Opioids bind G-protein-coupled receptors and regulate transmembrane signaling. The most commonly used opioids in pain management are µ agonists, which include morphine, meperidine, methadone, codeine, oxycodone, and the fentanyls. All of the µ-opioid agonists have similar pharmacodynamic effects at equianalgesic doses, including analgesia, respiratory depression, sedation, nausea and vomiting, pruritus, constipation, miosis, tolerance, and physical dependence. Although fentanyl is the least sedating of the opioids, it is the most commonly used analgesic for procedures and pain control in the PICU. It is short-acting following single doses (redistribution), but can be long-acting (“contextsensitive half-life”) following infusions.

Although fentanyl is the least sedating of the opioids, it is the most commonly used analgesic for procedures and pain control in the PICU. It is short-acting following single doses (redistribution), but can be long-acting (“contextsensitive half-life”) following infusions. Local anesthetics are beneficial for the treatment of procedure-related pain. They reversibly block conduction of neural impulses along central and peripheral nerve pathways.

Local anesthetics are beneficial for the treatment of procedure-related pain. They reversibly block conduction of neural impulses along central and peripheral nerve pathways. The systemic toxic effects of local anesthetics are determined by the total dose delivered, protein binding, rapidity of absorption into the blood, and the site of injection. Bupivacaine toxicity is the most dangerous and can lead to cardiac arrest and death.

The systemic toxic effects of local anesthetics are determined by the total dose delivered, protein binding, rapidity of absorption into the blood, and the site of injection. Bupivacaine toxicity is the most dangerous and can lead to cardiac arrest and death. Most sedatives, specifically benzodiazepines, chloral hydrate, propofol, and the barbiturates, have no analgesic properties.

Most sedatives, specifically benzodiazepines, chloral hydrate, propofol, and the barbiturates, have no analgesic properties. Long-term neuromuscular blockade, which has no analgesic or sedating qualities, should be reserved for clinical scenarios in which sedation and analgesia are adequate and immobility is necessary to facilitate recovery from the child’s illness.

Long-term neuromuscular blockade, which has no analgesic or sedating qualities, should be reserved for clinical scenarios in which sedation and analgesia are adequate and immobility is necessary to facilitate recovery from the child’s illness. It is imperative that the level of neuromuscular blockade is constantly monitored to prevent prolonged blockade and critical illness myopathy.

It is imperative that the level of neuromuscular blockade is constantly monitored to prevent prolonged blockade and critical illness myopathy. The interplay between sedation, sleep, and delirium is an important consideration in the comprehensive management of the critically ill child. Many of the drugs used for sedation and analgesia have deleterious effects on sleep, which can lead to a vicious cycle of increased sedation and analgesic needs and finally, delirium.

The interplay between sedation, sleep, and delirium is an important consideration in the comprehensive management of the critically ill child. Many of the drugs used for sedation and analgesia have deleterious effects on sleep, which can lead to a vicious cycle of increased sedation and analgesic needs and finally, delirium. Delirium is known to increase morbidity and mortality in critically ill patients, and validated screening tools are available to screen for this important entity.

Delirium is known to increase morbidity and mortality in critically ill patients, and validated screening tools are available to screen for this important entity.The treatment and alleviation of pain is a basic human right that exists regardless of age (1). Indeed, all of the nerve pathways essential for the transmission and perception of pain are present and functioning by 24 weeks of gestation (2). Failure to provide analgesia for pain to newborn animals and human newborns results in “rewiring” the nerve pathways responsible for pain transmission in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord and results in increased pain perception for future painful insults (3).

The PICU poses unique challenges for pain and sedation management. Hospitalization in general, and admission to the PICU in particular, are frightening and painful experiences  to children and their families. Pain in the PICU can be the result of the primary illness, trauma or the disease process, or the result of medical interventions. In addition, pain can be exacerbated by emotional distress and anxiety, two common components of the PICU stay. This distress may be the result of separation from one’s parents and family, being surrounded by unfamiliar people, sleep loss and fragmentation, and the fear of pain, loss of control, or even death (4). Thus, not only is pain control imperative in the critically ill but so too is the need for sedation. Nonpharmacologic measures such as open communication, reassurance, parental presence, sleep hygiene, and psychological interventions are helpful and essential in basic management. Nevertheless, many critically ill children need pharmacologically induced sedation to facilitate mechanical ventilation, invasive procedures, and treatment of multi-organ system dysfunction. Regardless of the methods used, the goals of sedation in the

to children and their families. Pain in the PICU can be the result of the primary illness, trauma or the disease process, or the result of medical interventions. In addition, pain can be exacerbated by emotional distress and anxiety, two common components of the PICU stay. This distress may be the result of separation from one’s parents and family, being surrounded by unfamiliar people, sleep loss and fragmentation, and the fear of pain, loss of control, or even death (4). Thus, not only is pain control imperative in the critically ill but so too is the need for sedation. Nonpharmacologic measures such as open communication, reassurance, parental presence, sleep hygiene, and psychological interventions are helpful and essential in basic management. Nevertheless, many critically ill children need pharmacologically induced sedation to facilitate mechanical ventilation, invasive procedures, and treatment of multi-organ system dysfunction. Regardless of the methods used, the goals of sedation in the  PICU are to provide a child with anxiolysis and comfort while maintaining safety to prevent inadvertent removal of invasive instrumentation such as endotracheal tubes and vascular access devices.

PICU are to provide a child with anxiolysis and comfort while maintaining safety to prevent inadvertent removal of invasive instrumentation such as endotracheal tubes and vascular access devices.

to children and their families. Pain in the PICU can be the result of the primary illness, trauma or the disease process, or the result of medical interventions. In addition, pain can be exacerbated by emotional distress and anxiety, two common components of the PICU stay. This distress may be the result of separation from one’s parents and family, being surrounded by unfamiliar people, sleep loss and fragmentation, and the fear of pain, loss of control, or even death (4). Thus, not only is pain control imperative in the critically ill but so too is the need for sedation. Nonpharmacologic measures such as open communication, reassurance, parental presence, sleep hygiene, and psychological interventions are helpful and essential in basic management. Nevertheless, many critically ill children need pharmacologically induced sedation to facilitate mechanical ventilation, invasive procedures, and treatment of multi-organ system dysfunction. Regardless of the methods used, the goals of sedation in the

to children and their families. Pain in the PICU can be the result of the primary illness, trauma or the disease process, or the result of medical interventions. In addition, pain can be exacerbated by emotional distress and anxiety, two common components of the PICU stay. This distress may be the result of separation from one’s parents and family, being surrounded by unfamiliar people, sleep loss and fragmentation, and the fear of pain, loss of control, or even death (4). Thus, not only is pain control imperative in the critically ill but so too is the need for sedation. Nonpharmacologic measures such as open communication, reassurance, parental presence, sleep hygiene, and psychological interventions are helpful and essential in basic management. Nevertheless, many critically ill children need pharmacologically induced sedation to facilitate mechanical ventilation, invasive procedures, and treatment of multi-organ system dysfunction. Regardless of the methods used, the goals of sedation in the  PICU are to provide a child with anxiolysis and comfort while maintaining safety to prevent inadvertent removal of invasive instrumentation such as endotracheal tubes and vascular access devices.

PICU are to provide a child with anxiolysis and comfort while maintaining safety to prevent inadvertent removal of invasive instrumentation such as endotracheal tubes and vascular access devices.Fortunately, there is an increased interest in pain and sedation research and in the development of pediatric pain services, primarily under the direction of pediatric anesthesiologists. Pain service teams provide the pain management for acute, postoperative, terminal, neuropathic, and chronic pain. In this chapter, we have tried to consolidate in a comprehensive manner some of the recent advances in pain and sedation management in an attempt to provide a better understanding of how to manage pain and sedation in the critically ill child.

PAIN AND SEDATION ASSESSMENT

Pain Assessment

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) defines pain as “an unpleasant and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage.” Pain is a subjective experience, and infants and children may be unable to describe their pain or  their subjective experiences. This has led many to conclude incorrectly that children do not experience pain in the same way that adults do. It is becoming increasingly clear that the child’s perspective of pain is an indispensable facet of pediatric pain management and an essential element in the specialized study of childhood pain. Pain assessment and management are interdependent and require accurate data about the location and intensity of pain, as well as the effectiveness of the measures being used to alleviate or abolish it.

their subjective experiences. This has led many to conclude incorrectly that children do not experience pain in the same way that adults do. It is becoming increasingly clear that the child’s perspective of pain is an indispensable facet of pediatric pain management and an essential element in the specialized study of childhood pain. Pain assessment and management are interdependent and require accurate data about the location and intensity of pain, as well as the effectiveness of the measures being used to alleviate or abolish it.

their subjective experiences. This has led many to conclude incorrectly that children do not experience pain in the same way that adults do. It is becoming increasingly clear that the child’s perspective of pain is an indispensable facet of pediatric pain management and an essential element in the specialized study of childhood pain. Pain assessment and management are interdependent and require accurate data about the location and intensity of pain, as well as the effectiveness of the measures being used to alleviate or abolish it.

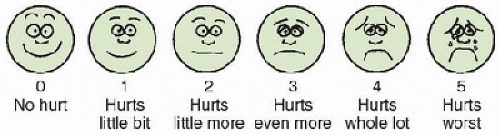

their subjective experiences. This has led many to conclude incorrectly that children do not experience pain in the same way that adults do. It is becoming increasingly clear that the child’s perspective of pain is an indispensable facet of pediatric pain management and an essential element in the specialized study of childhood pain. Pain assessment and management are interdependent and require accurate data about the location and intensity of pain, as well as the effectiveness of the measures being used to alleviate or abolish it.Instruments currently exist to measure and assess pain in children of all ages, although few have been validated for patients admitted to the PICU. The most commonly used instruments measure the quality and intensity of pain and are “self-report measures” that make use of pictures or word descriptors to describe pain. Pain intensity or severity can be measured in children as young as 3 years by using either the Oucher Scale, a two-part scale with a vertical numerical scale (0-100) on one side and six photographs of a young child on the other, or a visual analogue scale, a 10-cm line with a smiling face on one end and a distraught, crying face on the other. Because of its simplicity, the authors primarily use a simplified Six-Face Pain Scale originally developed by Dr. Donna Wong and modified by others (Fig. 14.1) (5). Obviously, self-report measures are impossible to use in intubated, sedated, and paralyzed patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree