PAIN: ABDOMEN

VINCENZO MANIACI, MD AND MARK I. NEUMAN, MD, MPH

Abdominal pain is a common complaint of children who seek care in the ED. Although most children with acute abdominal pain have self-limiting conditions, the presence of pain may herald a serious medical or surgical emergency. The diverse etiologies include acute surgical diseases (e.g., appendicitis, intussusception, strangulated hernia, trauma to solid or hollow organ), intra-abdominal nonsurgical ailments (e.g., gastroenteritis, urinary tract infection [UTI], gastric ulcer disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease), extra-abdominal conditions (e.g., pneumonia, pharyngitis, contusions of the abdominal musculature or soft tissue), systemic illnesses (e.g., “viral syndrome,” leukemia, diabetic ketoacidosis, vasoocclusive crisis from sickle cell anemia), and, commonly, functional abdominal pain. Making a timely diagnosis of an acute abdomen, such as appendicitis or volvulus, early enough to reduce the rate of complications, particularly in infants and young children, often proves challenging.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Abdominal pain can be stimulated by at least three neural pathways: visceral, somatic, and referred. Visceral pain generally is a dull, aching sensation caused by distention of a viscus that stimulates nerves locally and initiates an impulse that travels through autonomic afferent fibers to the spinal tract and central nervous system. The nerve fibers from different abdominal organs overlap and are bilateral, accounting for the lack of specificity to the discomfort. Children perceive the sensation of visceral pain generally in one of three areas: the epigastric, periumbilical, or suprapubic region. Somatic pain usually is well localized and intense (often sharp) in character. It is carried by somatic nerves in the parietal peritoneum, muscle, or skin unilaterally to the spinal cord level from T6 to L1. An intra-abdominal process will manifest somatic pain if the affected viscus introduces an inflammatory process that touches the innervated organ. Referred pain is felt at a location distant from the diseased organ and can be either a sharp, localized sensation or a vague ache. Afferent nerves from different sites, such as the parietal pleura of the lung and the abdominal wall, share pathways centrally. All three types of pain may be modified by the child’s level of tolerance. Individual variation exists such that some children with an appendiceal abscess will appear to have minimal pain, whereas other children with a functional etiology of their abdominal pain will appear quite distressed.

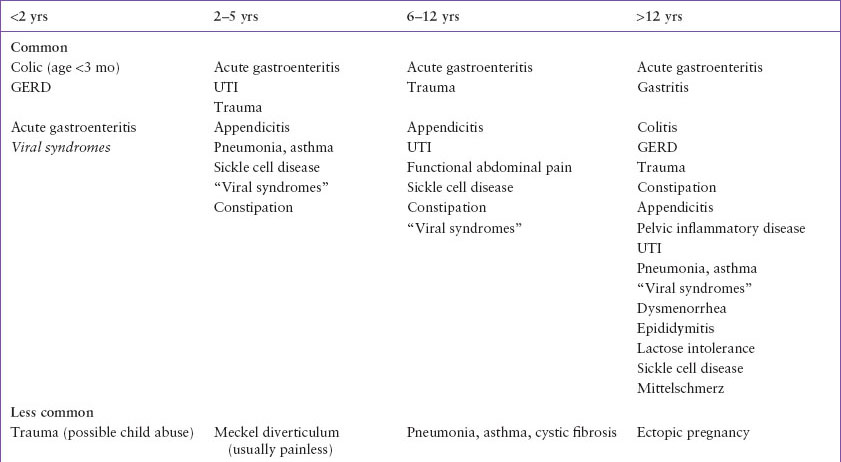

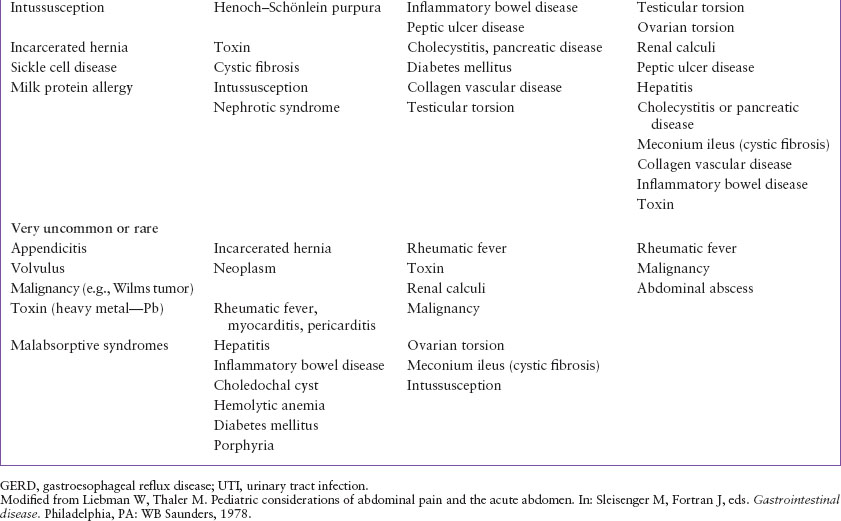

A number of illnesses that present with abdominal pain including conditions such as tonsillitis with high fever, viral syndromes, and streptococcal pharyngitis cannot be readily explained neurophysiologically as the triggers of abdominal pain. Despite the appearance of localized abdominal pain, clinicians need to perform a thorough physical examination that should include the assessment of the oropharynx, lung, skin, and genitourinary system. The principal causes of abdominal pain in children and adolescents are summarized in Table 48.1. Table 48.2 highlights the life-threatening disorders.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Intra-abdominal injuries can be life-threatening (such as hemorrhage from solid organ laceration or fluid loss and infection from perforated hollow viscus) and rarely may occur after minor trauma. An accurate history may not always be provided and, thus, clinicians must specifically inquire about a history of trauma in a child presenting with acute abdominal pain. Typical mechanisms include motor vehicle crashes, falls, and child abuse (see Chapter 111 Abdominal Trauma).

Bowel obstruction may occur as a result of adhesions in a child with previous abdominal surgery. Malrotation with volvulus, and necrotizing enterocolitis, should be considered in neonates with bilious emesis. Intussusception typically occurs among children 2 months to 2 years of age. Colicky abdominal pain is a typical feature of intussusception. The presence of blood in the stool, or “currant jelly stool,” is a relatively late finding among children with intussusception.

Among children of all ages, appendicitis can cause peritoneal irritation and focal tenderness. It occurs most commonly in children older than 5 years. The classic history of diffuse abdominal pain that later migrates to the right lower abdomen is not always elicited. The diagnosis of appendicitis in younger children can be more difficult and is often made later in the course of disease; as such, the rate of perforation in younger children is higher (see Clinical Pathway Chapter 83 Appendicitis (Suspected) and Chapter 124 Abdominal Emergencies for further information). Primary bacterial peritonitis is an uncommon cause of abdominal pain among children, but should be considered among children with nephrotic syndrome or liver failure.

Common conditions that are associated with acute abdominal pain include viral gastroenteritis, systemic viral illness, streptococcal pharyngitis, lobar pneumonia, and UTIs. Frequent causes of chronic or recurrent abdominal pain include colic (among young infants) and constipation. Other gastrointestinal (GI) conditions that may present with abdominal pain include inflammatory bowel disease (more often Chron’s disease than ulcerative colitis), cholecystitis (more common among children with predisposing conditions such as hemolytic anemia or cystic fibrosis or among older adolescents), pancreatitis, dietary protein allergy (typically in infants), malabsorption, and intra-abdominal abscesses (most commonly observed in children with perforated appendicitis).

Incarcerated inguinal hernia is an extra-abdominal cause of abdominal pain that can be life-threatening. A careful genitourinary examination should be performed in all children with abdominal pain. Myocarditis and pericarditis are rare extra-abdominal causes of abdominal pain. Systemic life-threatening conditions that can be associated with abdominal pain include diabetic ketoacidosis and hemolytic uremic syndrome. Other extra-abdominal conditions in which abdominal pain is often present include the following: Henoch–Schönlein purpura (usually with a distinctive purpuric rash over the lower extremities and buttock), vasoocclusive crisis with sickle cell syndromes, testicular torsion, urolithiasis (typically with colicky pain and flank tenderness), and toxic ingestions (such as lead or iron).

TABLE 48.1

CAUSES OF ACUTE ABDOMINAL PAIN

Functional abdominal pain should be considered among children with recurrent abdominal pain, but should be a diagnosis of exclusion. The pain rarely occurs during sleep and has no particular associations with eating, exercise, or other activities. The child typically has normal growth and development, and the abdominal examination is unremarkable; occasionally, mild midabdominal tenderness, without involuntary guarding, is elicited.

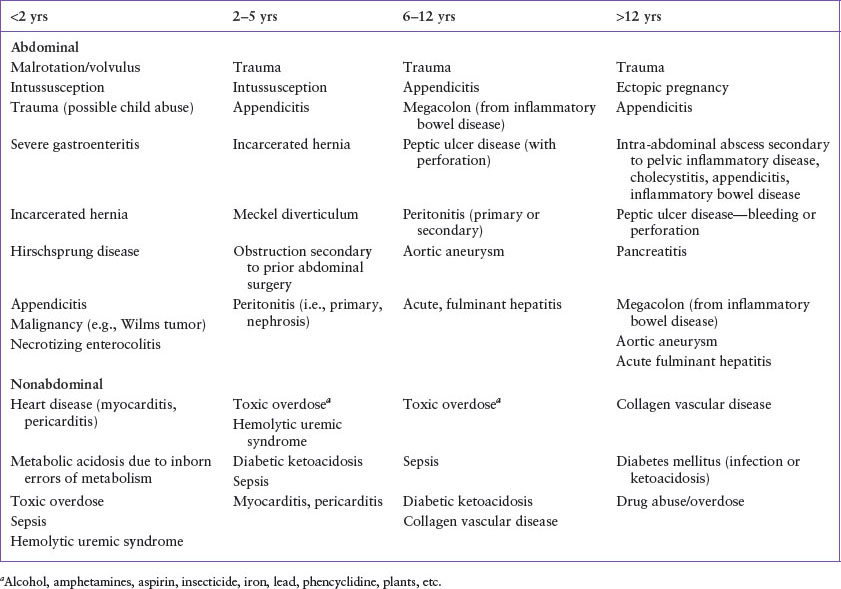

TABLE 48.2

LIFE-THREATENING CAUSES OF ACUTE ABDOMINAL PAIN

Among postmenarchal females, life-threatening conditions within the reproductive tract that can cause abdominal pain include pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) with tuboovarian abscess and ruptured ectopic pregnancy. Although intrauterine pregnancy may be associated with lower abdominal pain, ectopic pregnancy should always be considered.

EVALUATION AND DECISION

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree