CHAPTER 36

Otitis Media with Effusion; Serous (Secretory) Otitis Media (Glue Ear)

Presentation

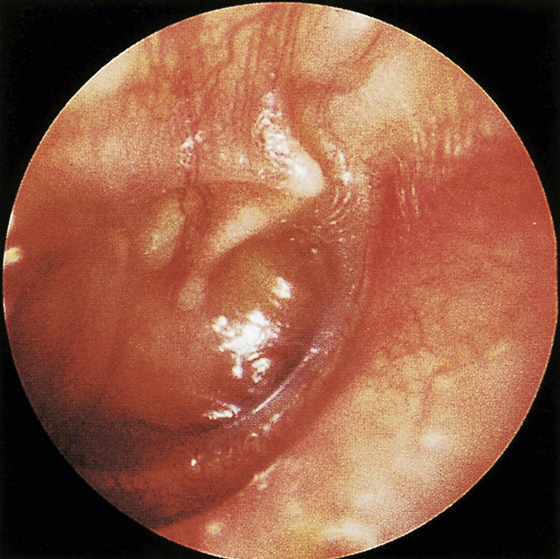

After an upper respiratory tract infection, an episode of acute otitis media (AOM), an airplane flight, or during a bout of allergies, an adult may complain of a feeling of fullness in the ears, an inability to equalize middle-ear pressure, decreased hearing, and a clicking, popping, or crackling sound, especially when he moves his head. There is little pain or tenderness. Otitis media with effusion (OME) is usually asymptomatic in children, except for tugging at the ears or signs of decreased hearing (lack of attention, talking too loud, sitting nearer to the television set). When viewed through the otoscope, the tympanic membrane (TM) appears retracted, with bony landmarks that are clearly visible and that are associated with a dull to normal light reflex with minimal if any injection. The best test to diagnose OME is pneumatic otoscopy, showing poor motion of the TM on insufflation. An air-fluid level or bubbles through the eardrum may be visible (Figure 36-1). There may be a lack of translucency, with a yellow or grayish effusion (Figure 36-2). Hearing may be decreased, and the Rinne test may show decreased air conduction (i.e., a tuning fork is heard no better through air than through bone).

Figure 36-1 Air-fluid level and bubbles visible through right retracted, translucent tympanic membrane in otitis media with effusion. (From Meniscus Educational Institute: Otitis media: management strategies for the 21st century. Bala Cynwyd, Pa, 1998.)

Figure 36-2 Severely retracted, opaque right tympanic membrane in otitis media with effusion. (From Meniscus Educational Institute: Otitis media: management strategies for the 21st century. Bala Cynwyd, Pa, 1998.)

It should be emphasized that there is no pain, fever or inflammation, or bulging of the TM, as one might expect to see in AOM (see Chapter 35).

What To Do:

In children without underlying developmental delay, preexisting hearing or vision problems, or other prior speech or language issues, OME can be observed for 3 months from the time of symptom onset or diagnosis without specific workup or treatment. If the OME lasts longer than 3 months or the child has preexisting problems, as outlined earlier, a hearing evaluation should be obtained.

In children without underlying developmental delay, preexisting hearing or vision problems, or other prior speech or language issues, OME can be observed for 3 months from the time of symptom onset or diagnosis without specific workup or treatment. If the OME lasts longer than 3 months or the child has preexisting problems, as outlined earlier, a hearing evaluation should be obtained.

Adults with OME may request symptomatic relief of the nasal congestion or middle-ear symptoms. Over-the-counter vasoconstrictor nose sprays, such as phenylephrine (Neo-Synephrine) or oxymetazoline 0.05% (Afrin), may be recommended.

Adults with OME may request symptomatic relief of the nasal congestion or middle-ear symptoms. Over-the-counter vasoconstrictor nose sprays, such as phenylephrine (Neo-Synephrine) or oxymetazoline 0.05% (Afrin), may be recommended.

Also, fluticasone (Flonase) topical corticosteroid spray may be prescribed (two sprays per nostril daily). However, in studies of children, neither vasoconstrictor sprays nor corticosteroids have been shown to lead to long-term resolution of OME.

Also, fluticasone (Flonase) topical corticosteroid spray may be prescribed (two sprays per nostril daily). However, in studies of children, neither vasoconstrictor sprays nor corticosteroids have been shown to lead to long-term resolution of OME.

Autoinflation has been shown to afford some improvement without side effects in audiometry at 1 month. To perform this, instruct the patient to insufflate his middle ear through the eustachian tube by closing his mouth, pinching his nose shut, and blowing until his ears “pop.”

Autoinflation has been shown to afford some improvement without side effects in audiometry at 1 month. To perform this, instruct the patient to insufflate his middle ear through the eustachian tube by closing his mouth, pinching his nose shut, and blowing until his ears “pop.”

A course of antibiotics may improve clearance of OME. Use the same antibiotics as for AOM. Do not prescribe more than one course.

A course of antibiotics may improve clearance of OME. Use the same antibiotics as for AOM. Do not prescribe more than one course.

Instruct the patient to seek follow-up with a primary care doctor or ear-nose-throat (ENT) specialist if the condition does not improve within 1 week.

Instruct the patient to seek follow-up with a primary care doctor or ear-nose-throat (ENT) specialist if the condition does not improve within 1 week.

Parents of children should be informed that bottle feeding, feeding a supine child, attending daycare, and living in a home in which people smoke increases the prevalence of OME.

Parents of children should be informed that bottle feeding, feeding a supine child, attending daycare, and living in a home in which people smoke increases the prevalence of OME.

What Not To Do:

Do not allow the patient to become habituated to vasoconstrictor sprays. After a few days of use, the sprays become ineffective, and the nasal mucosa develops a rebound swelling known as rhinitis medicamentosa, when the medicine is withdrawn.

Do not allow the patient to become habituated to vasoconstrictor sprays. After a few days of use, the sprays become ineffective, and the nasal mucosa develops a rebound swelling known as rhinitis medicamentosa, when the medicine is withdrawn.

Do not use oral antihistamines or decongestants. They have been shown not to be effective in the treatment of OME.

Do not use oral antihistamines or decongestants. They have been shown not to be effective in the treatment of OME.

Do not use oral or topical corticosteroids for the treatment of children with OME. There may be significant side effects with use of these medications in children. The American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines recommend against their use.

Do not use oral or topical corticosteroids for the treatment of children with OME. There may be significant side effects with use of these medications in children. The American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines recommend against their use.

Do not miss a nasopharyngeal mass, which should be considered in all patients with unilateral OME.

Do not miss a nasopharyngeal mass, which should be considered in all patients with unilateral OME.

Among children who have had an episode of AOM, as many as 45% have persistent effusion after 1 month. OME is defined as fluid in the middle ear without signs or symptoms of ear infection. Approximately 90% of cases of OME resolve spontaneously within 6 months. There is significant controversy regarding the routine treatment of this condition.

Most episodes resolve spontaneously within 1 to 2 months. The treatments described here are directed mainly at reestablishing normal function of the eustachian tube. It is unclear if any of these recommended treatments alter the natural course of this disease; therefore symptomatic relief should guide the clinician toward the most effective management for each individual patient.

Fluid in the middle ear is more common in children because of frequent viral upper respiratory tract infections and an underdeveloped eustachian tube. The highest incidence of OME occurs in children younger than 2 years, and the incidence decreases dramatically in those older than 6 years. Children are also more prone to bacterial superinfection of the fluid in the middle ear. When accompanied by fever and pain, this condition merits treatment with analgesics and antibiotics.

When the diagnosis of OME is uncertain, the patient should be referred for tympanometry or acoustic reflectometry. Children with persistent OME, who do not have the aforementioned risk factors, should be examined at 3- to 6-month intervals until the effusion clears or hearing abnormalities are discovered. Tympanostomy tube insertion is now recommended if there is hearing loss of 40 dB or greater persisting for 4 to 6 months. Repeated bouts of OME in an adult, especially if unilateral, should raise suspicion regarding a tumor obstructing the eustachian tube.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree