INTRODUCTION

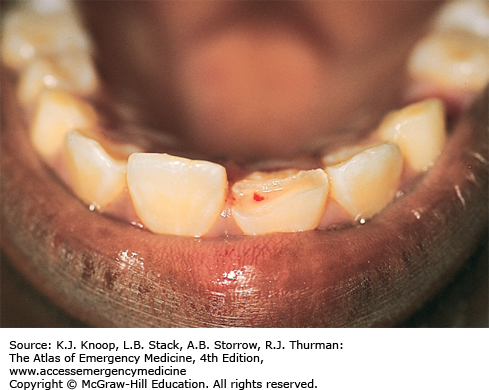

TOOTH SUBLUXATION

Tooth subluxation, the loosening of a tooth in its alveolar socket, is most commonly secondary to trauma; however, infection and periodontal disease may also produce subluxation. Gingival lacerations and alveolar fractures are associated with dental subluxations. Gentle pressure to the teeth with a tongue blade or fingertip may produce movement, mild displacement, or blood along the crevice of the gingiva, all signs of subluxation. Dental impaction and alveolar ridge fracture should be considered and ruled out clinically or radiographically.

Primary teeth: If the subluxated tooth is forced into close proximity to the underlying permanent tooth, follow-up for extraction is indicated. Otherwise, the patient should be instructed to follow a soft diet for 1 to 2 weeks, allowing the tooth to reimplant spontaneously.

Permanent teeth: Unstable teeth should be temporarily immobilized using gauze packing, a figure-eight suture around the tooth and an adjacent tooth, aluminum foil, or a special periodontal dressing, and the patient referred for dental follow-up.

Any evidence of tooth mobility following trauma is a subluxation by definition.

Always consider an associated underlying alveolar or occult root fracture.

TOOTH IMPACTION (INTRUSIVE LUXATION)

Impacted or intruded teeth result when a tooth is forced deeper into the alveolar socket or surrounding tissues as a result of trauma. The tooth appears shorter than its contralateral partner. An impacted tooth may be partially visible or completely hidden by the gingiva and buried in the alveolar process. Completely impacted teeth may erroneously be considered avulsed until a radiograph demonstrates the intruded position. The apex of a completely impacted permanent central incisor may be driven through the alveolar bone into the floor of the nares, causing epistaxis. Associated injuries may include alveolar fractures, dental crown or root fractures, and oral mucosal or gingival lacerations. Pulp necrosis occurs in 15% to 50% of cases.

Impacted primary teeth usually re-erupt and reposition spontaneously within 1 to 3 months. Any intruded primary tooth whose apex is displaced toward or impacts on the follicle of its permanent successor requires dental follow-up for extraction and monitoring clinically and radiographically for 1 year. Permanent teeth do not re-erupt. Surgical reduction is indicated to prevent complications such as external root resorption and loss of supporting bone. Orthodontic repositioning and splinting is generally carried out over 3 to 4 weeks.

An undiagnosed impacted tooth is predisposed to infection and may have a poor cosmetic result.

The maxillary incisors are the most commonly impacted teeth.

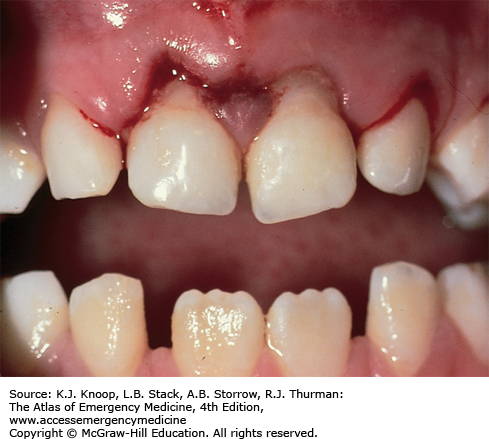

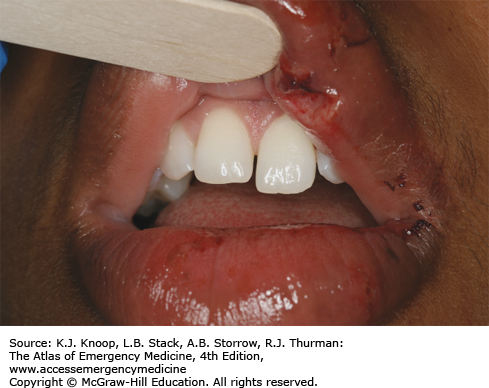

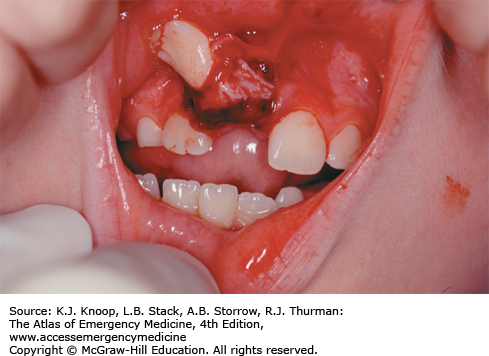

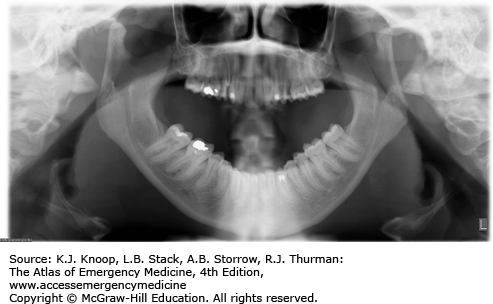

FIGURE 6.3

Tooth Intrusion. This impaction injury with multiple anterior maxillary tooth involvement shows various degrees of tooth impaction. Also note the complete absence of a central incisor. This may indicate a complete intrusion into the alveolar socket or an avulsion of the tooth. Radiographic studies are required when a tooth’s location is in question. (Photo contributor: James F. Steiner, DDS.)

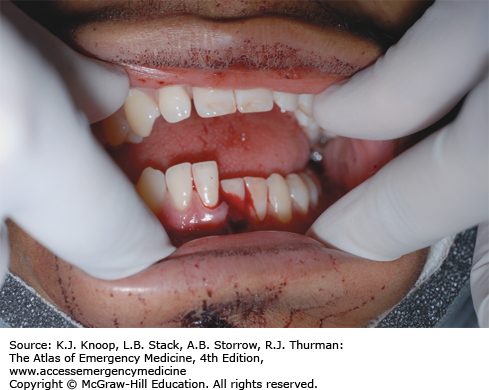

TOOTH AVULSION

Avulsion is the total displacement of a tooth from its socket. There is usually a history of trauma; however, infectious etiologies may result in complete disruption of the periodontal ligament from the affected tooth. Various degrees of bleeding from the socket and surrounding gingiva may be noted and there may be underlying alveolar fracture depending on the mechanism of injury. Prompt inquiry into the location of any unaccountable tooth is indicated. Radiographic evaluation to rule out aspiration, soft tissue entrapment, impaction, or dentoalveolar fracture is required when teeth are missing.

Successful reimplantation decreases by 1% for every minute the tooth is out of its socket. Permanent teeth should be replaced in their sockets as soon as possible. Successful reimplantation depends on the survival of periodontal ligament fibers; the tooth should be rinsed with saline, but not scrubbed, with care not to handle the root while replacing it in the socket. Emergent dental consultation, tetanus prophylaxis, and antibiotics targeting mouth flora are indicated. If not replaced, the avulsed tooth should be stored in the mouth of the patient or parent, or in a container of milk. Normal saline and commercial preservatives are reasonable alternatives, but tap water should not be used. Primary teeth are not reimplanted; reimplanted teeth may interfere with eruptions of permanent teeth because of ankylosis and fusion to the bone. Follow-up should be obtained for possible orthodontia until the permanent tooth erupts.

Primary teeth should not be reimplanted.

Successful reimplantation occurs best within the first 30 minutes.

Storage and transport media in decreasing order for preserving tooth viability include balanced salt solution or a tissue culture medium, chilled low-fat milk, saline, and saliva.

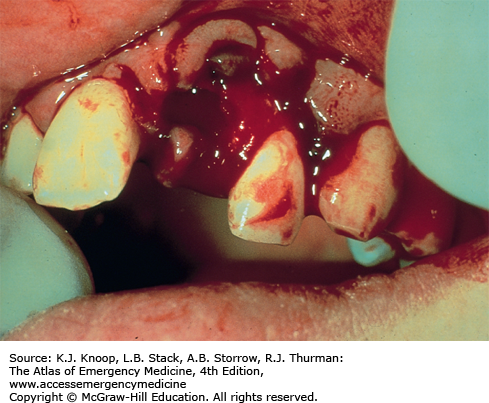

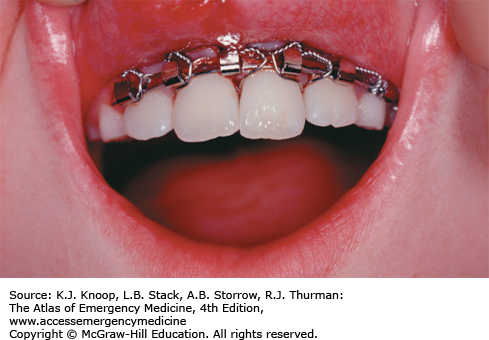

FIGURE 6.6

Tooth Avulsion Reimplanted. Reimplantation of the avulsed tooth in Fig. 6.5 was performed by an oral surgeon with the use of an arch bar to secure the tooth. (Photo contributor: Lawrence B. Stack, MD.)

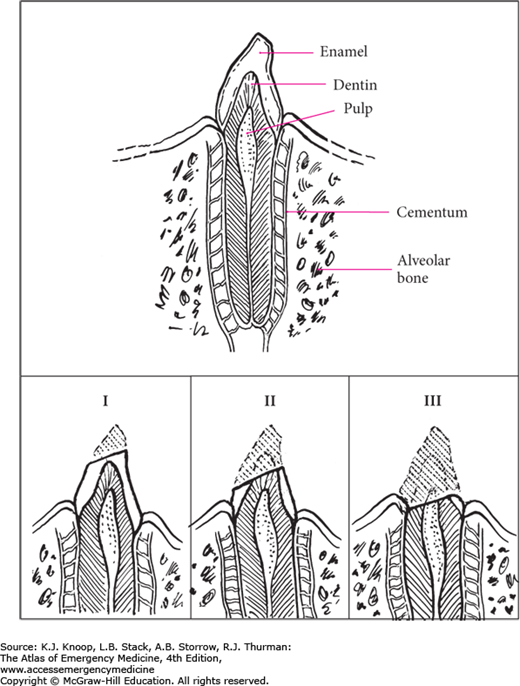

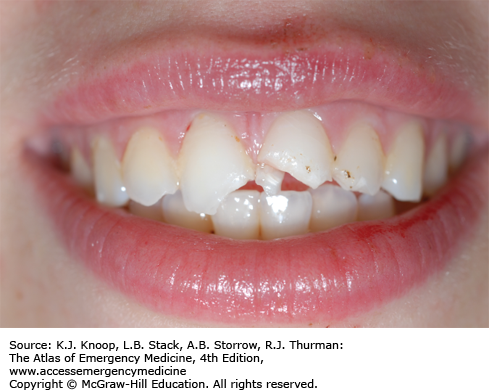

TOOTH FRACTURES

Anatomically, each tooth has a crown and root portion. Externally, the crown is covered with white enamel and the root portion with cementum. The cementoenamel junction (cervical line) is where the crown and root meet. The yellow-to-tan dentin is the second innermost layer and comprises the bulk of the tooth. The red-to-pink pulp tissue is located in the center of the tooth and includes the tooth’s neurovascular supply. The Ellis classification system is commonly used to describe tooth fractures above the cervical line in anterior teeth:

Ellis class I: Involves only the enamel.

Ellis class II: Involves the enamel plus exposure of the dentin. The patient may complain of temperature sensitivity.

Ellis class III: Fracture extends into the pulp. A pink or bloody discoloration on the fracture surface is diagnostic. The patient may have severe pain but may also have no pain due to loss of tooth nerve function.

Tooth fractures of the dental root may also occur below the cementoenamel junction and are commonly missed on initial evaluation. Bleeding may be observed at the gingival crevice with associated tooth tenderness on percussion. Radiographic evaluation may aid in differentiating these conditions.

Ellis class I: Pain control and referral for rough tooth edge and cosmetic management are indicated.

Ellis class II: Patients under 12 years of age have less dentin than older patients and are at risk for pulp infection. They should have a calcium hydroxide dressing placed, covered with gauze or aluminum foil, and seen by a dentist within 24 hours. Older patients should see a dentist within 24 to 48 hours.

Ellis class III: This is considered a dental emergency, and dental consultation within 24 to 48 hours is indicated. Delay in treatment may result in abscess formation.

Root fractures: Early reduction, immobilization/splinting, and dental referral within 24 to 48 hours are indicated. Most teeth sustaining root fractures maintain pulp viability.

Check for tooth mobility on initial examination to aid in differentiating mobility involving the entire tooth from involvement of only the fractured segment.

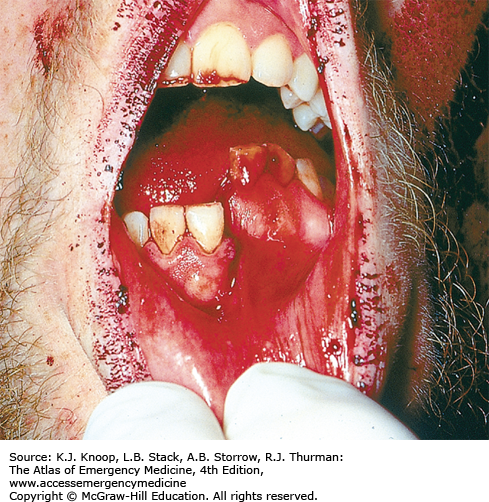

ALVEOLAR RIDGE FRACTURE

The alveolus is the tooth-bearing segment of the mandible and maxilla. Fracture of the alveolar process tends to occur most often in the thinner maxilla. The anterior alveolar processes are at greatest risk for fracture due to more direct exposure to trauma. Both subluxation and avulsion of teeth may be associated with underlying alveolar fractures. Various degrees of tooth mobility and gingival bleeding may occur.

Significant cosmetic deformity may result from alveolar bone loss; preservation of viable tissue is important. Gentle direct pressure over the alveolar segment with saline-soaked gauze, avulsed teeth preservation, and tetanus and antibiotic therapy administration are indicated. Oral surgery consultation should be obtained for possible wire stabilization or arch bar fixation.

Always consider the possibility of an associated cervical spine injury when evaluating patients with facial trauma.

Consider aspiration of avulsed teeth.

TEMPORAL MANDIBULAR JOINT DISLOCATION

Temporal mandibular joint (TMJ) dislocation generally occurs in predisposed individuals after a vigorous yawn or seizure, or less commonly from direct trauma to the chin while the mouth is open. Dislocation occurs when the mandibular condyles displace forward and become locked anterior to the articular eminence. Masseter muscle spasm contributes to prevention of spontaneous relocation. Weakness of the temporomandibular ligament, an overstretched joint capsule, and a shallow articular eminence are predisposing factors. Patients usually present with an inability to close an open mouth. Other associated symptoms include pain, discomfort, facial swelling near the temporomandibular joint, and difficulty speaking and swallowing. Anterior dislocations are most common; however, posterior dislocation may occur with significant trauma, often in association with basilar skull fractures. Unilateral dislocation results in deviation of the mandible to the unaffected side. TMJ hemarthrosis and dystonic reactions may mimic TMJ dislocations. Mandibular fractures should be considered if there is a history of facial trauma.

Acute reduction of pain, muscle spasm, and anxiety is achieved using reassurance, analgesics, and benzodiazepine muscle relaxants. Panorex or TMJ x-ray films (prereduction and postreduction) should be considered to exclude a fracture. A reduction maneuver is performed while facing the sitting patient and grasping the angles of the mandible with both hands. The thumbs are wrapped in gauze for protection and rest on the occlusive surfaces of the molars while downward and backward pressure is steadily applied until the condyle slides back into the articular eminence. Reduction may require some time and force to overcome muscle spasm. Following reduction, instruct the patient to avoid excessively wide mouth opening while eating and yawning for 3 to 4 weeks. Warm compresses to the TMJ, a soft diet for 1 week, and the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are advised. Dental/oral surgery follow-up should be arranged.

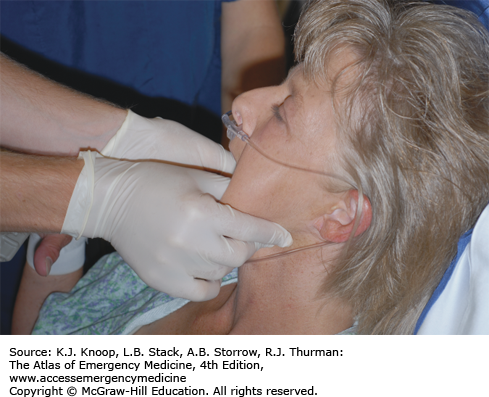

FIGURE 6.17

TMJ Reduction Technique. Under sedation, the patient in Fig. 6.16 undergoes reduction with inferior-posterior force applied by the physician. The thumbs are not wrapped with gauze in this case as the patient is edentulous. (Photo contributor: R. Jason Thurman, MD.)

TMJ dysfunction secondary to a neuroleptic or antipsychotic medication–related dystonic reaction is treated with diphenhydramine or benztropine.

When trauma is the cause of TMJ dislocation, maintain a high index of suspicion for mandible fractures and cervical spine injuries.

A reportedly successful technique for reduction of TMJ dislocation without sedation involves placing a syringe between the posterior molars and having the patient roll the syringe back and forth while gently biting down until reduction is achieved.

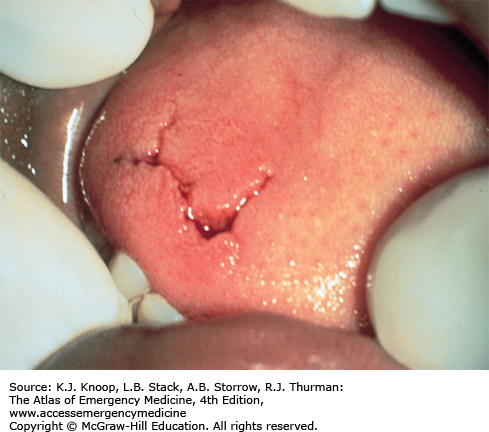

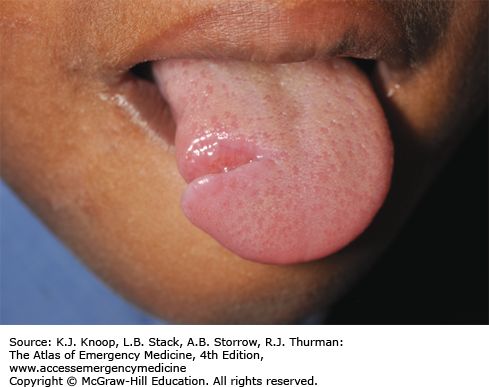

TONGUE LACERATION

Injuries to the tongue or mouth floor can cause serious hemorrhage and potential airway compromise and injury to or absence of teeth should be ascertained by inspecting the wound for possibly entrapped dental elements. Dorsal surface tongue lacerations may be associated with a mandibular surface laceration.

Most tongue lacerations do not require repair. Lacerations involving the tip or lateral margins or lacerations greater than 1 cm in length that gape widely or actively bleed are best stabilized by a few rapidly absorbable sutures using large bites to include both mucosa and muscle. Anesthesia of the anterior two-thirds of the tongue is obtained by an inferior alveolar/lingual nerve block. Local anesthesia, infiltrated at the site of the wound, may also be used.

Extensive complex tongue lacerations are at risk for infection and should be prophylactically treated with antibiotics covering oropharyngeal flora.

Regional anesthesia for tongue laceration repair avoids distortion of the anatomy prior to repair and is generally better tolerated than direct infiltration of local anesthesia into the tongue.

VERMILION BORDER LIP LACERATION

Anatomically, the vermilion border of the lips represents the transition area from mucosal tissue to skin. Lip lacerations involving the vermilion border present a unique clinical situation, since relatively minor malalignment may produce an unacceptable cosmetic result. An associated underlying gingival or dental injury is a common finding.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree