ORAL AND DENTAL ANATOMY

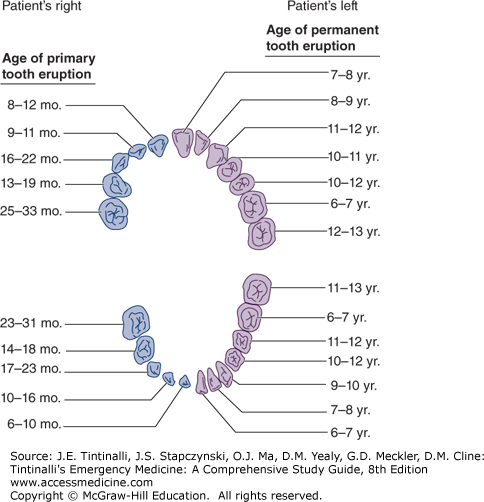

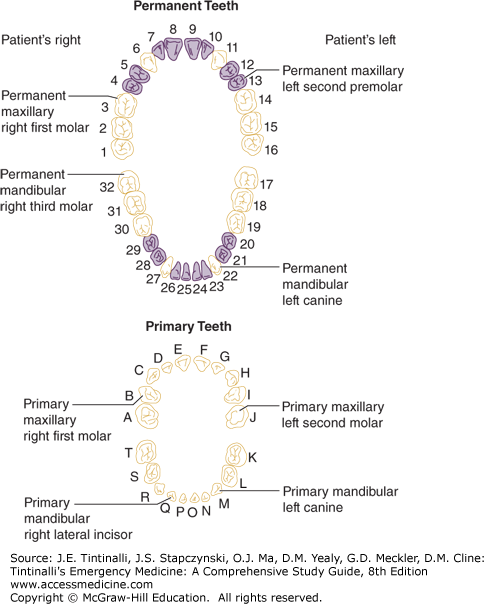

The normal adult dentition consists of 32 permanent teeth. The adult dentition has four types of teeth: 8 incisors, 4 canines, 8 premolars, and 12 molars. The primary or deciduous dentition consists of 20 teeth of three types: 8 incisors, 4 canines, and 8 molars. Figure 245-1 shows the eruptive pattern of both the primary and permanent dentition. Figure 245-2 illustrates the most commonly used tooth numbering system; however, description of the tooth type and location is also appropriate.

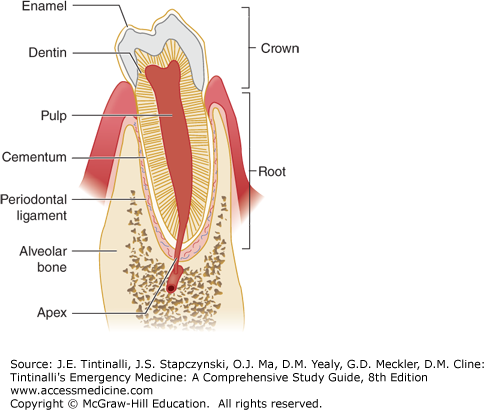

A tooth consists largely of dentin, which surrounds the pulp, the tooth’s neurovascular supply (Figure 245-3). Dentin is a homogeneous material produced by pulpal odontoblasts throughout life. Dentin is deposited as a system of microtubules filled with odontoblastic processes and extracellular fluid. The crown, or the visible portion of tooth, consists of a thick enamel layer overlying the dentin. Enamel, the hardest substance in the human body, consists largely of hydroxyapatite and is produced by ameloblasts before eruption of the tooth into the mouth. The root portion of the tooth extends into the alveolar bone and is covered with a thin layer of cementum.

The periodontium, or attachment apparatus, is essential for maintaining the integrity of the dentoalveolar unit. The attachment apparatus consists of a gingival component and a periodontal component. The gingival component includes the junctional epithelium, gingival tissue, and gingival fibers and primarily functions to maintain the integrity of the periodontal component. The periodontal component includes the periodontal ligament, alveolar bone, and cementum of the root of the tooth and forms the majority of the attachment apparatus. Disease states such as gingivitis and periodontal disease weaken and destroy the attachment apparatus, resulting in tooth mobility and tooth loss.1

Gingival tissue is keratinized stratified squamous epithelium. It can be divided into the free gingival margin and the attached gingiva. The free gingiva is the portion that forms the 2- to 3-mm-deep gingival sulcus in the disease-free state. The attached gingiva adheres firmly to the underlying alveolar bone. The nonkeratinized alveolar mucosa extends from the attached gingiva to the vestibule and floor of the mouth. The mucosal tissue of the cheeks, lips, and floor of the mouth is also comprised of nonkeratinized squamous epithelium.

OROFACIAL PAIN

Table 245-1 lists common causes of orofacial pain. Pain of dental origin may be diffuse in nature, presenting as a headache, sinus pain, eye pain, or jaw or neck pain, or may be localized to a single tooth. Remember to consider myocardial infarction as a cause of jaw pain.

| Nontraumatic Causes of Potential Dental Pain | |

| Odontogenic origin | |

| Tooth eruption | Cracked tooth syndrome |

| Pericoronitis | Periradicular periodontitis |

| Dental caries | Periapical abscess/facial space infection |

| Dentinal sensitivity/cervical erosion | Postextraction discomfort |

| Reversible pulpitis | Postextraction alveolar osteitis |

| Irreversible pulpitis | Post-restorative pain |

| Periodontal pathology | |

| Gingivitis | Periodontal abscess |

| Periodontal disease | Acute necrotizing gingivostomatitis |

| Gingival abscess | Peri-implantitis |

| Neurogenic/neurophysiologic syndromes | |

| Trigeminal neuralgia | Bell’s palsy |

| Other cranial neuralgias | Temporomandibular disorder |

| Nondental infections | |

| Oral candidiasis | Hand-foot-and-mouth disease |

| Herpes simplex types 1 and 2 | Sexually transmitted infections |

| Varicella-zoster, primary and secondary | Herpangina |

| Mumps | Sinusitis |

| Sialadenitis | Parotitis |

| Malignancies | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | Leukemia |

| Kaposi’s sarcoma | Melanoma |

| Lymphoma | Graft-versus-host disease |

| Other etiologies | |

| Aphthous ulcers | Pyogenic granuloma |

| Traumatic ulcers | Lichen planus |

| Stomatitis and mucositis | Cicatricial pemphigoid |

| Uremia | Pemphigus vulgaris |

| Vitamin deficiency | Erythema multiforme |

| Radiation/chemotherapy related | Crohn’s disease |

| Benign migratory glossitis | Behçet’s syndrome |

| Orofacial Trauma | |

| Dental fractures | Alveolar ridge fractures |

| Subtle enamel cracks/infractions | Facial bone fractures |

| Dental crown and/or root fractures | Oral soft tissue lacerations |

| Dental luxations and avulsions | |

Examine the soft tissue using a tongue depressor to expand your view looking specifically at the inner lips, the buccal and labial mucosa, the hard and soft palate, and the tongue and floor of the mouth. Ask the patient to extend the tongue, and gently grasp it with a piece of dry gauze, further extending it to the right and to the left, to expose each base. The floor of the mouth should be palpated with a finger in the mouth and one externally under the chin to check for a mass or lesion. Examine the teeth visually, and then gently percuss the suspected teeth with a firm clean object to determine if a specific tooth is the source of pain. After trauma, test for mobility and tenderness with gentle pressure and percussion. Assure that all the teeth occlude as normal for the patient. The degree of opening of the mouth should be evaluated. Palpate for potential fractures of the mandible of maxilla. Finally, the temporomandibular joint should be evaluated by placing your index fingers in the ears and feeling for crepitance or popping while the mandible is fully opened and closed.

Discomfort is commonly associated with the eruption of primary or deciduous teeth in infants. Irritability, drooling, and decreased intake are commonly associated findings. Approximately 11% to 12% of teething infants will have a mildly elevated temperature when examined in a doctor’s office, but a cause-and-effect relationship between teething and fever has never been demonstrated.2 Eruption of permanent teeth, especially third molars, or wisdom teeth, may cause pain. Gingival irritation and inflammation associated with tooth eruption are common and must be distinguished from pericoronitis. Pericoronitis is inflammation of the operculum, or the gingival tissue, overlying the occlusal surface of an erupting tooth. Impaction of food and debris beneath the operculum results in a severe inflammatory response. Without intervention, this progressive inflammatory process will result in localized infection. Because of the close proximity of the masticator space (comprised of the masseteric space, pterygomandibular space, and the superficial and deep temporalis space) to third molars, this infection can cause trismus. If the infection spreads into the connecting parapharyngeal spaces, it can be life threatening. Treatment of mild to moderate pericoronitis without associated systemic symptoms consists of appropriate antibiotic therapy such as penicillin VK, 500 milligrams PO four times a day, or clindamycin, 300 milligrams PO four times a day; local irrigation of food and debris from underneath the operculum; saline mouth rinses; and analgesia with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and opiates as appropriate. More severe cases may require IV antibiotics and admission. If pericoronitis is related to trauma from an opposing tooth during mastication, as is frequently the case with third molars, antibiotics and extraction of the opposing tooth will bring marked relief within 24 hours. For outpatient management, referral to a general dentist or an oral and maxillofacial surgeon within 24 to 48 hours is appropriate.3

Dental caries is the loss of integrity of the tooth enamel from hydroxyapatite dissolution by prolonged exposure to the acidic metabolic by-products of plaque bacteria. Caries most commonly occurs in areas where plaque accumulates such as pits and fissures of the occlusal surface, interproximally, and along the gingival margins. When a sufficient breach of enamel integrity occurs and the dentin is involved, caries spreads along dentinal microtubules. Direct communication between the oral environment and the vital dental pulp is established, and sensitivity to cold or sweet stimulus may result.

The pulpal inflammatory process is initially reversible, but with continued stimuli, the pulp’s ability to respond and repair is compromised. Irreversible pulpitis can be distinguished from reversible pulpitis by the duration of symptoms. In reversible pulpitis, the duration of pain is short, lasting seconds, as compared with irreversible pulpitis, in which the pain may last for minutes to hours. The most common stimulus is heat or cold, although sweet or sour stimuli also can elicit pain. Spontaneous tooth pain usually represents pulpal necrosis and is treated with analgesia; penicillin VK, 500 milligrams PO four times a day, or clindamycin in penicillin-allergic patients; and referral to a general dentist. Antibiotics for dental pain are controversial; two systematic reviews have concluded there is there is insufficient evidence to determine whether antibiotics for irreversible pulpitis reduce pain4,5 if there is no obvious infection. The use of local anesthetics as discussed in this chapter’s section on dental local anesthesia techniques can greatly reduce symptoms and should be considered for short-term pain management. The definitive treatment for irreversible pulpitis and pulpal necrosis is root canal therapy or dental extraction.

Cracked tooth syndrome is an incomplete fracture of a tooth that may extend into the vital pulp. Molars are most commonly affected. The patient experiences sharp pain on chewing that resolves when chewing ceases. Cold and sweet stimuli may also evoke pain. NSAIDs are frequently effective at temporarily controlling pain.3 The patient should avoid chewing on the affected side and see a dentist for definitive treatment.

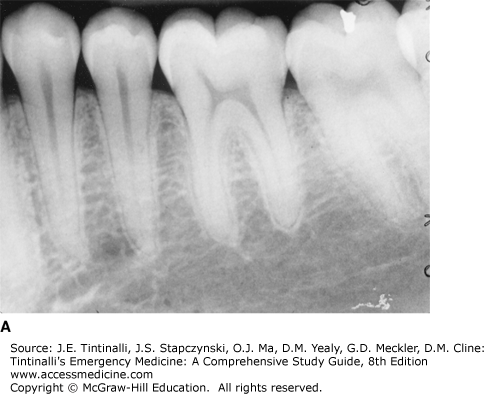

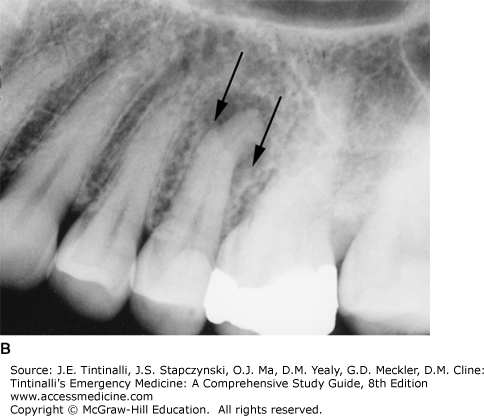

Acute periradicular periodontitis is the extension of pulp disease, inflammation, or necrosis into the tissues surrounding the root and apex of the tooth (deepest portion of the tooth socket). Occasionally it can be due to occlusal trauma. Periradicular lesions appear as a slight widening of the periodontal ligament space, a thinning of the lamina dura, or a radiolucent area associated with the root apex on a periapical dental radiograph. A Panorex is rarely useful for identification of all but the most extensive periradicular lesions, but can be important in identifying other painful osseous pathology (Figure 245-4).

FIGURE 245-4.

The radiographic appearance of a healthy tooth with a normal periodontal ligament space and distinct lamina dura (A) compared with the radiographic appearance of periapical radiolucency (arrows) consistent with periradicular periodontitis, a periapical abscess, or periradicular cyst (B). [Image used with permission of Gary M. Beaudreau.]

Pain on percussion of the suspected tooth with a light metal instrument, such as a handle of a dental mirror, helps to identify the offending tooth. Radiographically and clinically indistinguishable from periradicular periodontitis, a periapical abscess by definition contains a collection of pus. A small swelling of the gingiva with a draining fistula adjacent to the affected tooth is known as a parulis, and can help identify the involved tooth (Figure 245-5). If a dental abscess erodes through the cortical bone but does not drain spontaneously, then subperiosteal extension results in intraoral or facial swelling and fluctuance that should be incised and drained. Treat dental abscesses or other periapical lesions with penicillin VK, 500 milligrams PO four times a day, or clindamycin, 300 milligrams PO four times a day, and analgesia with an NSAID or opiate. Refer to a dentist for definitive treatment.

Spread of odontogenic infections into the various facial spaces is relatively common. Buccal extension of a periapical infection of the mandibular teeth will involve the buccinator space. Maxillary labial extension of infection primarily will involve the infraorbital space. Perforation through the lingual cortical bone of mandibular molars, particularly the second and third molars, usually occurs below the mylohyoid ridge and involves the submandibular space. Lingual spread of periapical infections associated with mandibular anterior teeth will affect the lingual space. The submandibular space and lingual space communicate with each other at the posterior border of the mylohyoid muscle. Cellulitis of bilateral submandibular spaces and the lingual space is called Ludwig’s angina and is potentially life threatening. As these spaces and the masticator space communicate directly with the parapharyngeal space, airway compromise is the immediate concern. For detailed discussion, see chapters 243, “Face and Jaw Emergencies” and 246, “Neck and Upper Airway.”

Infection of the infraorbital space may have a potentially devastating outcome if retrograde spread through the ophthalmic veins occurs and the cavernous sinus becomes involved. Cavernous sinus thrombosis presents as an infraorbital or periorbital cellulitis with rapidly developing meningeal signs, sepsis, and coma. Early recognition and treatment with a high-dose IV antibiotic, as above, are essential in decreasing morbidity and mortality.

Immediate postoperative pain is most commonly related to the trauma of surgery. Postoperative edema, such as with extraction of third molars, peaks within the first 24 to 48 hours and is best managed with ice packs, elevation of the head of the bed to 30 degrees, NSAIDs, and oral narcotics. Trismus, common immediately after extraction, can result from direct injury to the temporomandibular joint, injury to the muscles of mastication during administration of the inferior alveolar nerve block or during the surgery, and, most commonly, normal perioperative inflammation. Trismus peaks in the first 24 hours and usually decreases thereafter unless infection develops. Progressively worsening trismus is concerning for a postoperative infection.

Postextraction alveolar osteitis, or dry socket, usually occurs on the second or third postoperative day and is associated with exquisite oral pain. Total or partial displacement of the clot from the socket or fibrinolytic dissolution of the clot results in exposure of the alveolar bone and initiates a localized osteomyelitis of the exposed bone. Risk factors for developing postextraction alveolar osteitis include smoking, preexisting pericoronitis or periodontal disease, a traumatic extraction, a prior history of alveolar osteitis, and hormone replacement therapy.6 The incidence of postextraction alveolar osteitis is 1% to 5% of all extractions but is considerably higher (up to 30%) among impacted third molar extractions.6,7

Treatment is gentle irrigation of the socket with warmed normal saline or chlorhexidine 0.12% oral rinse.6,7,8,9 Local dental anesthesia (see the section on dental local anesthesia techniques) or topical anesthesia may be needed. Management of pain with NSAIDs or opiate medication is necessary. Antibiotic therapy with penicillin VK, 500 milligrams PO four times a day, or clindamycin, 300 milligrams PO four times a day, is reserved for the most severe cases. Refer for dental follow-up.6,7,8,9

Postextraction bleeding is not uncommon. Displacement of the clot may result in recurrent or continued bleeding. Generally, firm pressure applied to the extraction site is adequate to control bleeding. This is best accomplished by folding a 2 × 2-inch gauze pad and placing it over the extraction site and applying firm pressure by clenching with the opposing teeth. Pressure must be held firmly, not a chewing action, for 20 minutes or until hemostasis is complete. If direct pressure is not successful, then apply an absorbable gelatin sponge (Gelfoam®, Pfizer Inc., New York, NY), microfibrillar collagen (Avitene®, Davol, Inc., Warwick, RI), or regenerated cellulose (Surgicel®, Ethicon, Inc., Somerville, NJ) into the socket to provide a matrix for clot formation. Sutures can be used for holding such agents in place or to loosely close the gingiva over the socket. Do not suture the gingiva tightly because this may cause necrosis of the gingival flap. If this is not successful, careful injection of the soft tissue surrounding the extraction with lidocaine with epinephrine may control the bleeding. Careful cautery with silver nitrate can also be useful. If these methods are unsuccessful, then oral and maxillofacial surgical consultation is necessary.

Postrestorative pain can result from normal trauma from mechanical instrumentation of the tooth or direct exposure of the pulpal tissue during instrumentation. Pain associated primarily with mastication may be the result of improper occlusion of the new dental restoration or filling. After endodontic therapy, buildup of pressure in the pulpal chamber can cause severe pain. Provide NSAIDs or narcotic analgesia and refer to the patient’s dentist. Temporary prolonged pain relief can also be obtained using 0.5% bupivacaine with epinephrine and the appropriate dental anesthetic block as discussed in the dental local anesthesia technique section of this chapter. Follow-up with the dentist the next day then should be possible.

The most common emergency is a broken or bent wire that is irritating or lacerating the cheek or lip. This wire needs to be bent back away from soft tissue. This can easily be accomplished with dental instruments, or something soft like a pencil eraser can be used to gently bend the wire. Cutting the wire is generally not indicated as it makes the end sharper. The broken portion of the wire can be removed in its entirety by removing the rubber ligatures from each orthodontic bracket, but this generally is not necessary. The patient should follow up as soon as possible with the orthodontist.

Periodontal disease is a continuum of disease that begins with gingival inflammation and bleeding, or gingivitis, and can progress to destruction of the periodontal attachment apparatus, deepening of the normal gingival sulcus, periodontal pocket formation, bone loss, tooth mobility, and ultimately loss of teeth.1 Besides oral hygiene, many factors including hormonal variations, medications, and systemic disease can also influence periodontal health.

Periodontal disease usually progresses painlessly but may present as swollen gingival tissue or gingival bleeding. Treatment is directed at slowing or arresting the progression of disease primarily by the removal of plaque and its by-products.1 Antibiotics may play a role in treatment. Referral to a dentist for definitive treatment is indicated because the treatment involves extensive dental cleaning, instruction and improvement in oral hygiene, and in some cases, periodontal surgery.

A gingival abscess is an acutely painful swelling confined to the margin of the gingiva or interdental papilla. It usually rapidly enlarges over 24 to 48 hours, and purulent exudate can frequently be expressed from the orifice. The most common etiology is the entrapment of foreign matter such as a popcorn kernel, piece of meat, toothbrush bristle, or piece of food in the gingiva. Treatment includes identifying and removing the embedded foreign body and irrigating with normal saline. Continued home irrigation is beneficial, and symptoms resolve quickly.3

When plaque and debris are entrapped in the periodontal pocket, a periodontal abscess may form, resulting in severe pain. Small periodontal abscesses respond to local therapy with warm saline rinses and antibiotics such as penicillin VK, 500 milligrams PO four times a day, or clindamycin, 300 milligrams PO four times a day. Larger periodontal abscesses require incision and drainage. Chlorhexidine 0.12% mouth rinses twice daily are useful in the short term. Provide analgesia with NSAIDs or narcotics as indicated.3

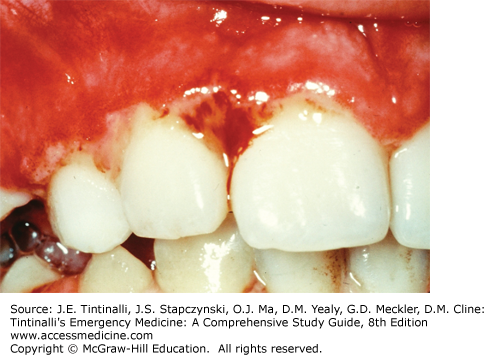

Acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis is an aggressively destructive process (Figure 245-6). Also known as Vincent’s disease or trench mouth, it is part of a spectrum of disease ranging from localized ulceration of the gingiva to often fatal noma, in which localized ulceration and necrosis spread to the adjacent tissues of the cheeks, lips, and underlying facial bones.10 The diagnostic triad includes pain, ulcerated or “punched out” interdental papillae, and gingival bleeding. Secondary signs include fetid breath, pseudomembrane formation, “wooden teeth” feeling, foul metallic taste, tooth mobility, lymphadenopathy, fever, and malaise.3,10

The differential diagnosis for acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis is quite extensive, but herpes gingivostomatitis is the most difficult to differentiate. Herpes gingivostomatitis usually has smaller vesicular eruptions, less bleeding, more systemic signs, and lack of interdental papilla involvement.10

The cause is still poorly understood. Acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis appears to be an opportunistic infection in a host with lowered resistance. Anaerobic bacteria such as Treponema, Selenomonas, Fusobacterium, and Prevotella invade otherwise healthy tissue, resulting in an aggressively destructive disease process.10,11 The most important predisposing factor is human immunodeficiency virus infection. A previous episode of necrotizing gingivitis is the second most important predisposing factor. Other contributing factors include poor oral hygiene, unusual emotional stress, poor diet and malnutrition, inadequate sleep, Caucasian descent, age <21 years old, poor socioeconomic status, recent illness, alcohol use, tobacco use, acatalasia, and various infections such as malaria, measles, and intestinal parasites.10,11

Treatment consists primarily of bacterial control. Chlorhexidine 0.12% oral rinses twice a day, professional debridement and scaling, and adjunctive antibiotic therapy with metronidazole, 500 milligrams PO three times a day, are the mainstay of treatment. Reduction in pain can be expected within 24 hours of institution of this regimen. Identification and resolution of the predisposing factors and supportive therapy with a soft diet rich in protein, vitamins, and fluids are important in establishing and maintaining a disease-free state.10,11

Osseointegrated dental implants have become common over the last 30 years, allowing for a dental implant to replace a tooth. However, as with any procedure, complications do occur, and problems related to implants may present to the ED. Pathologic changes around an implant are all given the general term of peri-implant disease. Patients who present with peri-implantitis present with a similar presentation to that of a periodontal abscess and require similar treatment. Gentle removal of the plaque and debris from around the implant and irrigation with normal saline or 0.12% chlorhexidine solution should be done. Antibiotic treatment with metronidazole, 500 milligrams PO three times a day for 10 days, or amoxicillin, 500 milligrams PO three times a day for 10 days, is indicated. Give analgesia as needed, and refer to a dentist for definitive care.3

Trigeminal neuralgia is the most common of the craniofacial neuralgias. Other significantly less common neuralgias of the craniofacial region include glossopharyngeal neuralgia, vagal neuralgia, and superior laryngeal neuralgia involving the respective nerve distributions. Post–herpes zoster–related neuralgia is also a cause of acute facial pain and may become chronic in nature. See chapter 165, “Headache” for further discussion.

Bell’s palsy is a peripheral unilateral weakness of the facial nerve of unknown etiology. As part of the differential diagnosis for orofacial pain, patients with a facial nerve palsy related to herpes zoster may present with nonspecific facial pain prior to the onset of weakness or the onset of any visible vesicles. In such cases, this diagnosis must be considered. See chapter 243 for a more extensive discussion on facial nerve palsy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree