INTRODUCTION

NEONATAL CONJUNCTIVITIS (OPHTHALMIA NEONATORUM)

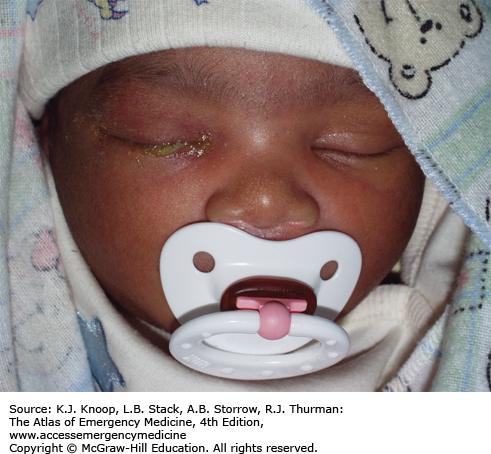

Neonatal conjunctivitis is acquired either during birth with passage through the mother’s cervix and vagina, or from cross-infection in the neonatal period. Presenting symptoms for Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection include a hyperacute bilateral conjunctivitis with copious purulent discharge, lid swelling, chemosis, and preauricular adenopathy.

More common etiologies include Chlamydia trachomatis, viruses (herpes simplex), and bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcal pneumoniae, Haemophilus species). For chlamydial conjunctivitis, the clinical features range from mild swelling with a watery discharge to marked lid swelling with a red and thickened conjunctiva with a blood-stained discharge. Fluorescein staining of herpes simplex conjunctivitis demonstrates epithelial dendrites.

With any form of neonatal conjunctivitis, Gram stain and culture are indicated. Scrapings of the palpebral conjunctiva are more likely to be rewarding than examination of the discharge itself. Begin treatment in the emergency department (ED) and admit newborns with suspected gonococcal conjunctivitis. Evaluate concurrently for C trachomatis, since coinfection is common.

Treatment for chlamydial conjunctivitis is based upon a positive diagnostic test. While culture is the gold standard, nucleic acid amplification tests, despite lacking FDA approval, are reported to perform similarly. Untreated disease can result in corneal and conjunctival scarring. Bacterial neonatal conjunctivitis that is neither gonococcal nor chlamydial may be treated with erythromycin antibiotic ointment and should be reevaluated in 24 hours.

Herpes simplex conjunctivitis is treated with intravenous (IV) acyclovir and topical trifluridine. Despite the appearance of a localized herpes infection, there is high risk for central nervous system (CNS) or disseminated infection.

Evaluation of the newborn’s parents should be undertaken in neonatal conjunctivitis due to Gonococcus, Chlamydia, or herpes simplex virus (HSV).

The “rule of fives” may help predict the most likely bacterial cause.

| Print

0-5 days

5 days-5 weeks

5 weeks-5 years

Gonococcus

Chlamydia

Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Haemophilus

Blindness can result from gonococcal eye infection in the neonate because the organism can invade the cornea. It is one of the few emergency conjunctival infections.

Nasolacrimal duct obstruction is common (up to 20%) in newborns and may present with findings suggestive of conjunctivitis. It is a diagnosis of exclusion in the neonate.

Advise parents that infants treated with macrolides are at risk for developing hypertrophic pyloric stenosis.

| Etiologic Agent | Time of onset | Clinical Features | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical | Day 1 | Common with silver nitrate; erythromycin more commonly used now for this reason | Self-limited |

| N gonorrhoeae | Day 2-7 | May cause hyperacute disease with profuse discharge | Ceftriaxone IV. Caution in hyperbilirubinemia. Topicals alone inadequate |

| C trachomatis | Day 3-14 | Clinical severity varies. Common cause of blindness worldwide | Erythromycin PO Azithromycin (alternate) |

| HSV 1,2 | Day 2-16 | Should be suspected if child has any vesicular lesions on body | Vidarabine or trifluridine topically; consider systemic acyclovir |

| Other bacterial organisms | Day 2 and up | Empiric treatment based on Gram stain | Erythromycin ointment for gram positive; gentamicin or tobramycin ointment for gram negative |

BACTERIAL CONJUNCTIVITIS

Bacterial conjunctivitis is characterized by the acute onset of conjunctival injection and a thick yellow, white, or green mucopurulent drainage. Lid edema, erythema, and chemosis may also be seen. S aureus is the most common causative bacteria. Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae occur more frequently in children.

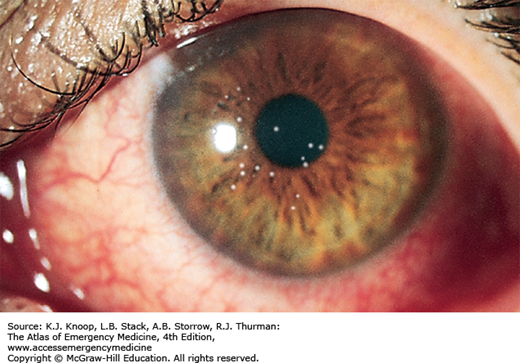

Hyperacute bacterial conjunctivitis, the most severe form of acute purulent conjunctivitis, is associated with N gonorrhoeae. Symptoms are hyperacute in onset, and findings include a purulent, thick, copious discharge, eyelid swelling and tenderness, marked conjunctival hyperemia, chemosis, and preauricular adenopathy. The condition is serious and threatens sight because Neisseria species are capable of invading an intact corneal epithelium. Corneal findings include epithelial defects, marginal infiltrates, and an ulcerative keratitis that can progress to perforation.

Encourage frequent hand washing and warm moist compresses. Empiric antibiotic choices include polymyxin/trimethoprim drops and erythromycin ophthalmic ointment. Other options include bacitracin, sulfacetamide, or polymyxin-bacitracin ointments or fluoroquinolone or azithromycin drops. Improvement should be noted in 1 to 2 days. Patients who do not improve should be referred to an ophthalmologist.

Fluoroquinolones should be prescribed for contact lens wearers (and keratitis ruled out) due to concern for Pseudomonas infection. Hyperacute bacterial conjunctivitis requires immediate ophthalmologic consultation and hospitalization.

Conjunctivitis is a common presentation of the red eye, and should be considered after more serious causes, such as acute angle-closure glaucoma (ACG), iritis, and infectious keratitis, have been ruled out.

Red flags include a significantly decreased visual acuity, ciliary flush, and corneal opacity.

Worsening symptoms during topical treatment with Neosporin or a sulfonamide suggest a contact allergic reaction.

N gonorrhoeae conjunctivitis must be considered in the sexually active adult with a prominent, thick, copious discharge. Urethritis is usually present.

Fluoroquinolones should be prescribed for contact lens wearers because of concern for Pseudomonas infection in these patients.

VIRAL CONJUNCTIVITIS

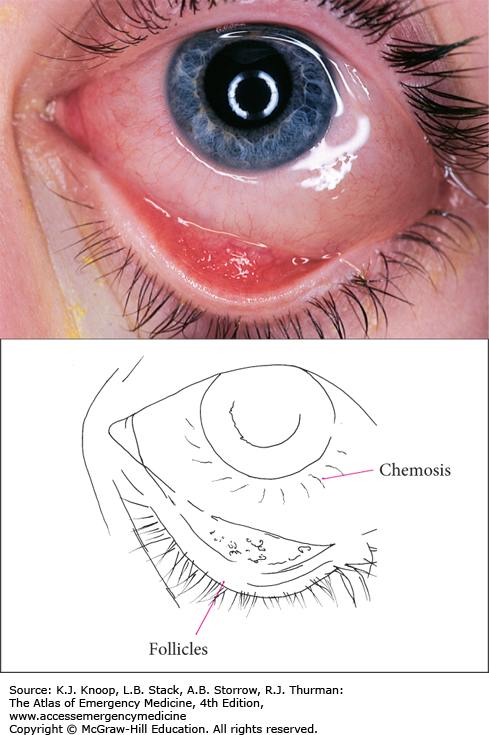

Viral conjunctivitis is a common presentation of the red eye. Findings are mild and include a thin watery discharge, crusting in the morning, burning or irritation, conjunctival injection (typically diffuse), and lid edema. The tarsal conjunctiva may appear bumpy secondary to hyperplastic lymphoid tissue (follicles). Preauricular adenopathy may be present. The visual acuity is normal. The infection usually begins in one eye, but both eyes usually become involved due to autoinoculation. There are few to no systemic complaints. Adenovirus is the most common virus. A point of care test now available may aid clinicians to avoid empiric antibiotic therapy.

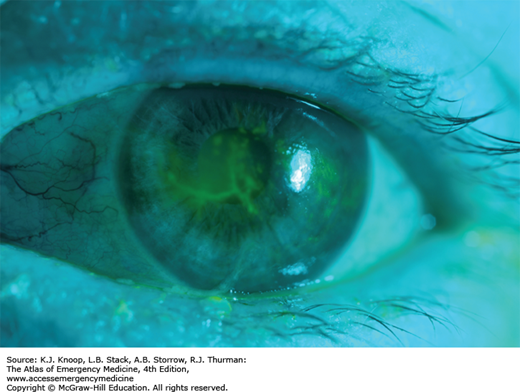

Epidemic keratoconjunctivitis (EKC) is a severe and highly contagious adenovirus infection that also involves the cornea. Additional features may include foreign body sensation, photophobia, and pseudomembranes overlying the palpebral conjunctiva. By the eighth day, a painful punctate keratitis that stains with fluorescein may develop; by the end of the second week, these are replaced by white macular subepithelial infiltrates located in the central cornea (that no longer stain). These may cause a decrease in visual acuity, but eventually resolve spontaneously.

Pharyngoconjunctival fever, usually caused by adenovirus type 3, is highly contagious and should be considered if there is associated upper respiratory tract infection and fever.

Viral conjunctivitis is self-limited and usually mild. Warm or cool compresses may be helpful. Careful hand washing by patient and staff is important. Over-the-counter topical antihistamines (Naphcon A) may provide symptomatic relief. The eye irritation and discharge should improve after 5 to 7 days, but may take 2 to 3 weeks for complete resolution of all symptoms. Antivirals and antibiotics are ineffective. Patients with keratitis should follow up with an ophthalmologist.

A nonspecific adenovirus conjunctivitis will improve after 5 to 7 days and resolve in 10 to 14 days, but a virulent adenovirus causing EKC will peak in 5 to 7 days and may last 3 to 4 weeks.

Consider and rule out serious causes of red eye (acute ACG, iritis).

Frequent hand washing and the use of separate linens are advised for patients and family members.

Fastidious hand and equipment hygiene is necessary to prevent nosocomial transmission, as adenovirus can be recovered for extended periods of time from these surfaces.

ALLERGIC CONJUNCTIVITIS

Allergic conjunctivitis is a condition whereby airborne allergens precipitate type 1 IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reactions in the conjunctiva. Allergens include pollens, animal dander, mites, mold, and dust. Approximately 50% of patients have a personal or family history of allergic conditions such as atopy, eczema, asthma, and allergic rhinitis.

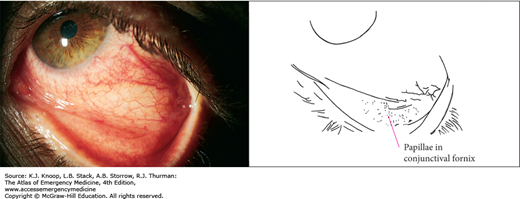

Itching is the hallmark symptom. Associated clinical features include conjunctival injection and edema, burning, discharge (clear, white, or mucopurulent), chemosis, and eyelid redness and swelling. Small papillae may be seen on the tarsal conjunctiva.

Vernal conjunctivitis is a rare but serious form of allergic conjunctivitis. The highest incidence is seen in the arid areas of the Middle East and North Africa secondary to wind and dust storms. Symptoms are similar to allergic conjunctivitis, but are more intense. Itching is severe and a vigorous knuckle rubbing is a typical observation. Giant, raised, pleomorphic papillae (“cobblestones”) seen over the upper tarsal plate are pathognomonic.

The initial approach is to eliminate the allergen. Avoiding animal dander, using air conditioners with appropriate filters, and limiting time outdoors will improve the condition. Topical tear substitutes are effective to dilute or wash away the allergen. H1 antihistamine-vasoconstrictor combinations such as over-the-counter Naphcon A are recommended to relieve mild itching and redness. For more severe or frequent attacks, olopatadine, an antihistamine with mast cell stabilizing properties, is more effective. Mild topical steroids are an option only after consultation with an ophthalmologist.

Options for vernal conjunctivitis include cromolyn, aspirin, and cold compresses. Topical cyclosporin may be useful in resistant cases.

Itching is the hallmark symptom of allergic conjunctivitis.

Itching is not common in nonallergic conjunctivitis.

Symptoms are usually bilateral.

Naphcon A and olopatadine are effective in treating allergic conjunctivitis.

Complications of topical corticosteroid use include glaucoma, cataract formation, secondary infection, and corneal perforation.

DACRYOCYSTITIS

Dacryocystitis is an inflammation of the lacrimal sac, positioned immediately distal to the canaliculi and proximal to the nasolacrimal duct. Inflammation is usually secondary to obstruction of the nasolacrimal duct. Clinical findings include swelling over the lacrimal sac, redness, tearing, eyelash matting and crusting, and conjunctival redness. Tears and mucopurulence may be expressed from the punctum when pressure is applied over the lacrimal sac. Complications include conjunctivitis and orbital or preseptal cellulitis.

Up to 20% of normal newborns have a closed nasolacrimal passage, and 90% spontaneously open within the first 6 months.

Ophthalmologic consultation is recommended. The most common organisms isolated in children are S aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and α-hemolytic Streptococci. Oral clindamycin for 7 to 10 days is recommended for outpatient management. Febrile and acutely ill patients require IV vancomycin in combination with a third-generation cephalosporin.

Treatment of nasolacrimal duct obstruction is managed initially with downward lacrimal sac massage (“Crigler” massage) 2 to 3 times a day. Unresolved nasolacrimal duct obstruction requires lacrimal duct probing by the ophthalmologist.

Nasolacrimal duct obstruction is the most common cause of persistent tearing and ocular discharge in children.

Swelling is localized to the extreme nasal aspect of the lower lid and may be confused with a hordeolum. Occasionally, conjunctival redness may be present.

Dacryocystitis may be confirmed by pressure on the lacrimal sac and the reflux of tears and purulent material from the punctum. The lacrimal sac and lacrimal fossa lie in the inferior medial aspect of the orbit, not on the side of the nose.

Urgent referral should be made for any signs of orbital cellulitis. These include proptosis, limitation of extraocular movements, and loss of vision.

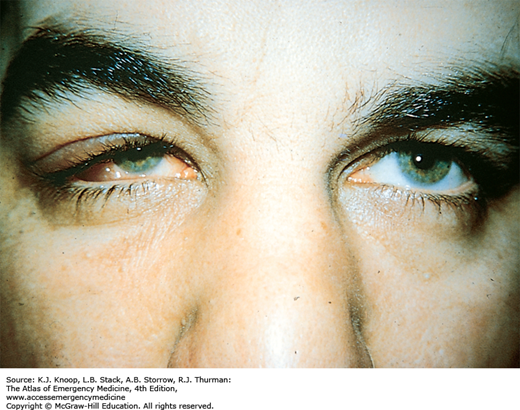

DACRYOADENITIS

Acute dacryoadenitis typically involves children and young adults with associated systemic infections such as gonorrhea, mumps, Epstein-Barr virus, and Staphlyococcus species. Findings are localized to the outer one-third of the upper eyelid and include fullness or swelling, erythema, and tenderness. A characteristic “S”-shaped deformity with ptosis of the lid may be seen. In more advanced cases proptosis, inferonasal globe displacement, ophthalmoparesis, and diplopia may be present.

Chronic dacryoadenitis is more common, is seen in older patients, and is usually due to tumor or associated inflammatory disorders such as sarcoidosis, Sjögren syndrome, or IgG4-related diseases.

For acute dacryoadenitis, amoxicillin-clavulanate or IV ampicillin-sulbactam are used, depending on the severity and patient’s toxicity. In cases of dacryoadenitis due to mumps or Epstein-Barr virus, warm compresses are recommended. Resolution occurs spontaneously. Patients should return to the ED for symptoms suggestive of orbital cellulitis such as decreased ocular motility or proptosis.

Treatment of chronic dacryoadenitis involves treatment of the underlying disorder.

Nonemergent ophthalmology follow-up is appropriate.

Swelling is localized over the lateral one-third of the upper lid and imparts an “S”-shaped curve to the lid margin.

Acute dacryoadenitis is usually seen as a complication of mumps, with (bilateral) parotid swelling.

Chronic dacryoadenitis is more common, and is seen in older patients. Malignancy should be considered.

IgG4-related disease should be considered in patients (particularly middle-aged and older men) with bilateral disease and either salivary gland enlargement or pancreatitis of unknown origin.

Urgent referral is recommended for patients with diplopia, limitation of the extraocular muscles, or reduction of vision.

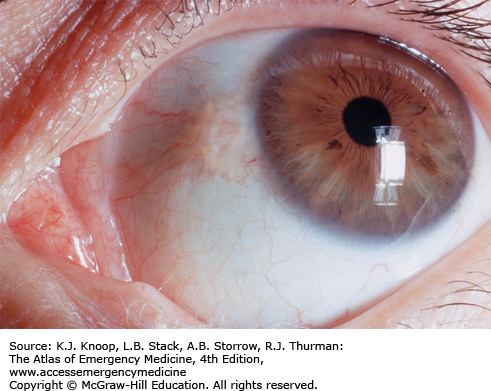

PTERYGIUM/PINGUECULA

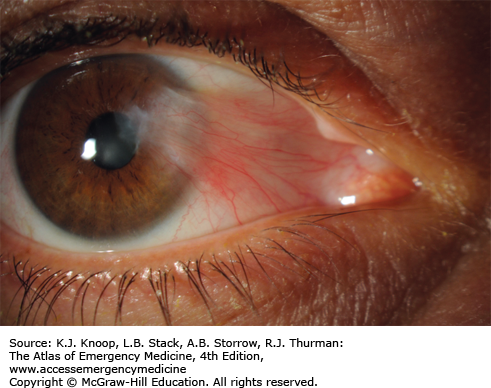

Pterygium (Greek, pterygion meaning wing-like) is a benign proliferation of fibrovascular tissue. It usually originates in the nasal conjunctiva on the horizontal meridian of the limbus. It progressively encroaches onto the cornea and visual axis. Its appearance ranges from flat and white to thick, pink or red, and fibrovascular. Typically, it assumes a triangular appearance, the apex directed toward the pupil. Predisposing factors include exposure to ultraviolet light, wind, and dust. Older individuals living in warmer areas with high levels of sunlight are more likely to develop pterygia.

Pterygia may be asymptomatic or become inflamed, causing mild symptoms of irritation and foreign body sensation. Decreased visual acuity may result as the pterygium encroaches on the visual axis or if the lesion induces astigmatism.

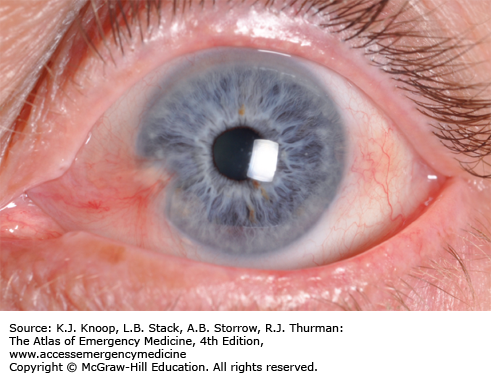

Pinguecula (Latin, pingueculus meaning fatty) is a common degenerative lesion of the bulbar conjunctiva, also arising in the horizontal meridian. It appears as a light brown or yellow-white amorphous, slightly raised conjunctival tissue adjacent to the limbus. It too may be asymptomatic or become episodically inflamed; however, it may enlarge and become a pterygium.

Mild disease can be treated with artificial tears or a topical vasoconstrictor (Naphcon A). In more severe cases, consultation with an ophthalmologist is appropriate regarding topical steroids and topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Surgical excision by the ophthalmologist is indicated if the pterygium interferes with contact lens wear, encroaches significantly on the visual axis resulting in induced astigmatism or opacity, or restricts eye movement.

Pterygia are more likely than pinguecula to be found on the nasal conjunctiva and bilateral.

Pterygia and pingueculae are found on the horizontal meridian. Conjunctival neoplasms often occur in axes other than the horizontal axis.

Following surgical excision, recurrence of pterygia is common.

Pterygium-mimics include localized conjunctival neoplasia, conjunctivitis, and episcleritis.

HORDEOLUM/CHALAZION

A hordeolum is a localized abscess involving the glands of the eyelid. An external hordeolum (stye) involves an eyelash (cilia) follicle or the tear glands of the lid margin (glands of Zeis, Moll). An internal hordeolum involves the meibomian glands. S aureus is the most frequent isolate. Clinical findings include focal swelling, edema, erythema, and tenderness.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree