Operational Performance and Preventive Medicine

Scott E. Young

Guillermo J. Pierluisi

OBJECTIVES

After reading this section, the reader will be able to:

1. Discuss previous preventive measure strategies used in tactical operations.

2. List specific potential medical risks for tactical personnel.

3. Discuss health surveillance and maintenance.

4. Describe strategies used for mitigation of potential medical threats.

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

The practice of tasking personnel to preventive medicine duties within the U.S. Armed Forces (or would be U.S. Armed Forces) dates back to the Revolutionary War (1). One of General George Washington’s first general orders issued at Headquarters, Cambridge, Massachusetts, July, 4 1775, addressed to line officers whom he held responsible for the health of their men, reads:

All officers are required and expected to pay diligent attention to keep their men neat and clean; to visit them often at their quarters, and inculcate upon them the necessity of cleanliness, as essential to their health and service. … They are also to take care that necessarys (latrines) be provided in the camps and frequently filled up to prevent their being offensive and unhealthy.

History has also shown us that the implementation of preventive medicine interventions is needed in every field operation. Furthermore, it has shown us that any omission or delay in the implementation, laxity in the enforcement or lack of surveillance after implementation can be most deleterious to the field units. For example:

1. During World War II, 95% (November 1942 to August 1945) and 77% (November 1942 to August 1945) of the U.S. Army hospital admissions in the Pacific and European Theaters of Operations, respectively, were for disease and nonbattle injuries (DNBI) (2). During the winter of 1943 alone, frostbite caused more casualties among the port gunners on B-17 and B-24 bombers (due to exposure to cold air rushing by at more than 200 miles per hour as they opened the doors to fire their machine guns) than all other sources combined (3).

2. During Operation Desert Shield-Storm (1990-1991), despite our general success against DNBI, sporadic outbreaks of diseases and preventable injuries occurred when preventive medicine principles were ignored. A food outbreak affecting 648 individuals working on the flightline in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, occurred on January 20, 1991 (4). The implicated food source was a locally catered meal served throughout the day. In Desert Shield preventable injuries were responsible for most deaths among U.S. soldiers (5). The 3rd Armored cavalry regiment outpatient sick call records reflects that noncombat orthopedic trauma and unintentional injuries accounted for the greatest number of lost duty days and evacuations from theater (6).

3. During the early phases of Operation Restore Hope in Somalia (1992-1993), epidemic mosquito borne malaria and dengue occurred in an infantry battalion, affecting nearly 10% of the troops. Command emphasis on personal protective measures was lacking (5).

The incidence of preventable illness during tactical operations is not acceptable, because the teams are usually small and can become completely ineffective with the loss of only a few of the teammates. Because of this, the medical personnel of tactical operation teams must be very aware of the types of injuries and preventable illnesses seen in this work environment.

Operational Performance and Preventative Medicine Philosophy

The tactical medic’s job is to maximize mission success by providing appropriate medical care before, during, and after missions. The most important aspect of this job is to prevent injury and illness from occurring, not just treating injury as it occurs. Tactical operations are inherently dangerous, and minimizing the risk to operators not only keeps them safe and injury free, but also ensures the success of the mission. Most special operations units have operators with unique attributes and capabilities. The loss of one of these members (e.g., sniper) to a preventable injury, such as a corneal abrasion from a tree branch, can significantly impact the success of a mission.

Injury prevention starts with adequate medical planning. Predicting medical threats associated with specific situations and developing medical assets and transport systems to accommodate potential injuries will help to minimize morbidity and mortality in the hazardous tactical environment.

Preparing operators before deployment with appropriate physical conditioning, health surveillance and immunizations will also help to ensure mission success. By addressing these issues prior to deployment, the provider will minimize medical equipment needs and will be able to inform the mission commander of any significant health-related issues that may impact operator performance.

Physician level medical oversight is essential in establishing good preventative medicine in the tactical community. This ensures the best guidance to the tactical medical provider, and protects the medical team in the event of an untoward outcome. The licensed practitioner is ultimately responsible to the tactical commander for all preventative medicine measures applied by members of the tactical medical team.

Preventative medicine in the operational environment has a broad scope, covering topics from food handling to immunizations to injury prevention during incidents. By addressing these issues before, during, and after deployment, the tactical medic will help to ensure operator well being and mission success.

MECHANISMS OF PREVENTION

Surveying Potential Medical Risks

The tactical medical provider should take as much time as possible leading up to deployment to assess the potential medical threats that members of the tactical team may face based on the intelligence given for a particular situation. The amount of time tactical medical personnel have to complete this planning may be minutes to weeks, depending on the type of incident. When developing a written survey of possibly medical hazards, the medic should work closely with the mission commander to ensure that he/she is informed of potential risks/complicating factors associated with a given situation and can possibly make alterations in mission planning where needed. This information should be documented in a concise, legible format so that it can be easily distributed to team members as needed.

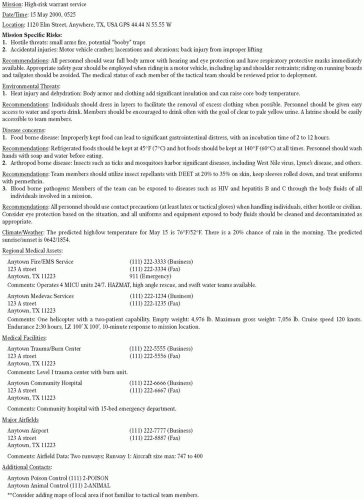

The following is a list of data to be included in the development of medical risk survey. For each category, the survey should identify all conceivable risks and propose solutions to prevent operator illness or injury in a brief and easily referenced manner (Fig. 17.1).

1. Incident specific risks: Opposition weapon systems, known or possible chemical/biological warfare agents, preplanned evacuation routes, weapon systems utilized by the tactical team, entry methods, and other specific threats and hazards that members of the tactical team may face based on the situation.

2. Environmental health threats: Extreme heat or cold, hydration needs, nutritional needs based on the intensity of operator activity, sanitation considerations, risks associated with local wildlife/plant life, and specific risks associated with unique terrain (i.e. mountainous, desert, waterborne, etc).

3. Disease concerns: Should include diseases not covered by standard vaccinations, potential food borne illness, body fluid precaution risk, and region specific disease concerns as dictated by local departments of health or the Center for Disease Control.

4. Climate/weather forecast: Climate can be predicted based on location and time of year. An extended forecast should be obtained, in the event of prolonged or sustained operations. These can also be updated actively during deployments.

5. Regional medical assets: If air/ground evacuation support for casualties is not part of the deploying unit, the tactical medic should be aware of local/regional medical assets available from the civilian community, or possibly the military. If the potential exists for the utilization of medical evacuation assets outside of the tactical team, consideration should be made to informing these services in advance of the operation. This release of intelligence is clearly dependent on the secrecy of the situation.

6. Medical facilities: In addition to planning for casualty evacuation, the tactical medical team should know locations and distances to the closest medical facilities, the closest trauma center, and the closest burn center. Locations for hyperbaric chambers should also be noted if dive operations are planned. The ability to communicate with such facilities including radio frequencies and telephone numbers should be obtained. An assessment of the capabilities to include trauma center designation, ED physician staffing capabilities,

ancillary service availability (e.g., CT scan), presence of a helipad and its specifications, and which specialties are represented at the facility should be obtained in the planning phase.

ancillary service availability (e.g., CT scan), presence of a helipad and its specifications, and which specialties are represented at the facility should be obtained in the planning phase.

7. Hazardous materials teams (HAZMAT): Contact information for local/regional/national HAZMAT services should be available regardless of whether or not this type of threat is anticipated.

Most of this information can be obtained via the internet and possibly a few phone calls. For the medical facilities and regional medical assets, face-to-face contact is the ideal option, as it helps them understand the mission and what to possibly expect in the event of casualties. This interaction is clearly limited by the level of operational security, which needs to be clearly established by the mission commander prior to any data collection. The ATF raid on the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, Texas, was compromised by an OPSEC breach for medical planning and extreme caution must be used when interacting with outside agencies and civilian EMS.

Because the time from the start of incident planning to actual deployment is extremely variable, it is important for the tactical unit to maintain records of previous risk surveys, which can be reused in the event of a return to the same location or environment. By developing a thorough risk assessment survey, the tactical medic can help prevent a great deal of unnecessary injuries as well as be better equipped to handle medical incidents as they occur.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree