Fig. 24.1.

Inguinal neuroanatomy (From Chen et al. [11] with kind permission Springer Science + Business Media).

Fig. 24.2.

Retroperitoneal neuroanatomy (From Wagner et al. [12], with kind permission ©McGraw-Hill Education).

The IIN lies over the anterior surface of the spermatic cord and is covered by the investing fascia of the internal oblique muscle. During inguinal hernia repair, this fascia protects the nerve from direct contact with the mesh and should not be disrupted. Contrary to prior teaching, dissection of the IIN from the cord should be avoided because destruction of this protective fascia increases the risk of perineural scarring or entrapment by the implanted mesh.

The genital branch of the GFN enters the deep inguinal ring and traverses the inguinal canal within the spermatic cord. It is covered by the deep cremasteric fascia, which protects it from contact with the mesh. Its location is most easily identified by its close proximity to the external spermatic vein, which appears as a blue line immediately adjacent to the nerve. When isolating the cord, care must be taken to visualize the nerve and maintain its position with the other cord structures as the cord is separated from the inguinal floor. The deep cremasteric fascia should be kept intact to avoid perineural scarring or contact between the nerve and mesh.

The IHN lies between the internal and external oblique muscle layers of the abdominal wall. The investing fascia of the internal oblique protects the nerve from contacting the mesh. The IHN can be identified by opening the anatomic cleavage between the internal and oblique layers high enough to expose the internal oblique aponeurosis. This simple maneuver allows for easy identification of the portion of the nerve that lies superficial to the internal oblique aponeurosis. There is an additional, more proximal segment of the nerve that lies within the internal oblique muscle. This intramuscular segment is commonly injured because it is not visible during hernia repair. Suturing the internal oblique muscle to the inguinal ligament or mesh implant can potentially result in injury or entrapment of this segment. In approximately 5 % of patients, the IHN runs deep to the internal oblique aponeurosis, passing directly through the internal and external oblique layers simultaneously and is not visible within the inguinal canal at the time of initial repair, placing this nerve at risk [7]. This should be noted by the operating surgeon at the visible point of its exit, and care should be taken to avoid passing suture or fixation material through the internal oblique aponeurosis in the anticipated course of this nerve, risking injury or entrapment of the underlying nerve.

Surgical Management of Neuropathic Pain

Operative management for pain after inguinal surgery has been reported as early as 1942 with Magee describing genitofemoral causalgia as a source for post-inguinal surgery pain [13]. Selective IIN, IHN, and GFN neurolysis or neurectomy, removal of mesh and fixation material, and revision of the prior herniorrhaphy are common but less effective options for treatment [14–16]. Neurolysis, which does not address ultrastructural changes of nerve fibers, has limited efficacy and is not recommended [5]. Simple removal of entrapping sutures or fixating devices while leaving the injured nerves behind is also inadequate [5]. Selective single or double neurectomy may be effective for some patients, but does not address ultrastructural changes or microscopic neuromas of seemingly normal-appearing nerves during reoperation [14–16]. For patients with high probability of isolated neuropathy based on history, symptoms, mechanism (e.g., IHN entrapment in a Pfannenstiel incision, neuropathy from isolated trocar site, or LFC injury from lateral tack placement), physical examination including dermatomal mapping/distribution, and sensory testing, selective neurectomy is reasonable in experienced hands. However, for most anterior hernia repairs and posterior approaches utilizing fixation, multiple nerves may be involved, and triple neurectomy is more effective.

From a technical perspective, reoperation in the scarred field increases difficulty and morbidity for subsequent remedial operations. Anatomically, the significant variation and cross-innervation of the inguinal nerves in the retroperitoneum and inguinal canal make selective neurectomy less reliable [5]. A recent study by Bischoff et al. described their experience with selective neurectomy in 54 patients with chronic pain after open mesh repair [17]. The IIN, IHN, and GFN were identified in 40 (74 %), 20 (37 %), and 13 (24 %) patients, respectively, illustrating the challenge of reoperative nerve identification in experienced hands. It is difficult to precisely isolate the inguinal nerves involved, and frequently there is more than one nerve implicated in postherniorrhaphy chronic neuropathic pain. Triple neurectomy of the IIN, IHN, and genital branch of the GFN, pioneered in our institute in 1995, is currently a universally accepted surgical treatment for neuropathic pain refractory to conservative measures and is arguably the most effective option [5, 18]. Our experience has included over 700 patients using an open approach with a success rate of over 85 % and 50 selected cases using a laparoscopic retroperitoneal approach with a 90 % success rate. Operative neurectomy in conjunction with removal of meshoma, when present, provides effective relief in the majority of well-selected patients with refractory neuropathic inguinodynia [5].

Timing and Patient Selection

A systematic approach is imperative for proper identification of patients suited for operative intervention. Recommended timing of surgical intervention for postherniorrhaphy pain unresponsive to standard nonsurgical modalities is 6 months to 1 year after the original hernia repair [1, 5]. Failure of conservative measures, in of itself, is not an indication for further surgery. Successful outcomes are entirely dependent upon choosing patients with discrete neuroanatomic problems amenable to surgical correction. A thorough preoperative evaluation should include symptomatology, review of the prior operative report for technique (specifically, the type of repair, type of mesh used, position of the mesh, method of fixation, and nerve handling), imaging to assess for meshoma or other anatomic abnormalities, and response to prior interventions [5, 19]. The patients most likely to benefit from operative neurectomy are those with neuropathic pain isolated to the inguinal distribution that was not present prior to the original operation and that showed improvement with diagnostic and therapeutic nerve blocks.

Risks of Surgery

Operative remediation of inguinodynia carries risk of complications, including refractory pain, exacerbation of underlying pain, deafferentation hypersensitivity, and anticipated permanent numbness involving unilateral labial numbness and potential associated sexual dysfunction in women. Risks related to reoperation in the scarred field include bleeding, disruption of the prior hernia repair, recurrence, vascular injury, and testicular loss. These risks should be discussed with the patient and documented prior to proceeding to operation.

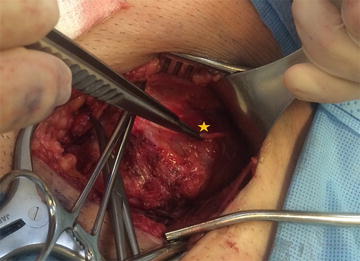

Technique

Triple neurectomy involves resecting segments of the IIN, the genital branch of the GFN, and the IHN from a point proximal to the original surgical field to the most distal accessible point. The main trunk of the GFN over the psoas muscle may also be resected in the case of pain after open or laparoscopic preperitoneal hernia repair, as described below [20]. This chapter focuses on open triple neurectomy with laparoscopic triple neurectomy described separately. Exposure for open triple neurectomy typically utilizes the same incision as the original anterior repair. If the original repair was done laparoscopically, a standard inguinal incision is used. Extending the incision more cephalad and lateral than typical for a hernia repair facilitates the exposure of the proximal portions of the IIN and IHN. Additionally, this allows for access to the inguinal canal proximal to scarred mesh within the canal.

The IIN is typically identified lateral to the deep inguinal ring and divided as proximally as possible (Fig. 24.3). The IHN is identified in the plane between the internal and external oblique aponeurosis. It is traced proximally to its intramuscular segment and divided proximal to the field of the original repair. Including the intramuscular segment in the resection avoids missing an occult injury in this segment. If the IHN is noted to be one of the subaponeurotic variants described previously, the internal oblique aponeurosis is split proximal to the point where the nerve traverses both internal and external oblique aponeurosis, and this hidden portion of the nerve is divided (Fig. 24.4). The genital branch of the GFN is identified adjacent to the external spermatic vein under the cord or through the lateral crus of the internal ring. In a standard triple neurectomy for pain after anterior repairs, it is ligated and divided at the internal ring (Fig. 24.5).