OCULAR TRAUMA

CINDY G. ROSKIND, MD AND ALEX V. LEVIN, MD, MHSc, FRCSC

GOALS OF EMERGENCY CARE

The clinical evaluation of children with eye trauma should focus on the prompt recognition of the most severe eye injuries, without causing additional damage to the eye, and the initiation of timely ophthalmologic consultation. The most important goal is to quickly recognize those injuries in need of emergent consultation with ophthalmology (Table 122.1).

KEY POINTS

Prioritize and stabilize the ABCs—the management of life-threatening injuries must be prioritized over any eye injury.

Prioritize and stabilize the ABCs—the management of life-threatening injuries must be prioritized over any eye injury.

The first step in the examination of the traumatized eye should be to assess the visual acuity of both the injured and the unaffected eye.

The first step in the examination of the traumatized eye should be to assess the visual acuity of both the injured and the unaffected eye.

Ensure the structural integrity of the eye quickly and rule out the presence of a ruptured globe.

Ensure the structural integrity of the eye quickly and rule out the presence of a ruptured globe.

RELATED CHAPTERS

Signs and Symptoms

• Eye: Unequal Pupils: Chapter 24

• Eye: Visual Disturbances: Chapter 25

Medical, Surgical, and Trauma Emergencies

• Child Abuse/Assault: Chapter 95

HISTORY

When approaching a patient with eye trauma, the emergency physician should quickly assess the child’s relevant past history in order to assess the expected baseline visual acuity. The mechanism of injury should also be ascertained in order to understand the risk of serious ocular pathology and predict injury patterns. Finally, the patient should be asked about current symptoms including pain, decrease in vision, foreign body sensation, photophobia, or tearing.

Assessment of Prior Eye Pathology and Relevant Medical History

It is important to quickly establish the child’s prior ocular history in order to assess the anticipated baseline visual acuity. A history of prior poor vision including use of contact lenses or glasses, amblyopia, or strabismus surgery should be queried. If the child is wearing contact lenses, they should be removed. A history of systemic disorders may predispose some children to specific injuries or worse outcomes. For example, patients with collagen disorders are more prone to globe rupture, and patients with hemoglobinopathies have a higher incidence of rebleed post hyphema.

Assessment of Injury Mechanism

Clinicians should assess the exact mechanism of injury as the type of trauma and the nature of the force inflicted may predict injury patterns and prognosis. For example, significant blunt impact directly to the eyeball (e.g., baseballs), projectiles and sharp objects (e.g., sticks or pencils) have high risk of intraocular damage. Severe blunt trauma may cause orbital fractures and can also rupture the globe. Projectiles pose great risk to the globe, and globe rupture sustained following gun injury tends to lead to poor visual outcome. Hammering is a particularly high-risk behavior for intraocular foreign bodies.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Every attempt should be made to examine the eye with the child in a position of comfort in order to minimize agitation, particularly if the history or gross appearance of the eye suggests the possibility of a ruptured globe. If at any point the examination is concerning for a ruptured globe, the physician should stop the examination, shield the eye, and consult with an ophthalmologist emergently.

1. Assess Visual Acuity

The first step in the examination of the eye should be an attempt to assess the visual acuity of both the injured and the unaffected eye. The presence of bilaterally poor vision in a patient with unilateral eye trauma suggests that the cause of the poor vision may be unrelated to the trauma.

Some patients may be unable to perform this task because of eye pain, noncompliance, inability to open swollen lids, or obtundation from accompanying head trauma. Even if the eyelids remain closed, the physician should test for light perception. By shining a bright light in the direction of the eyeball through the closed eyelid, the physician can ask the patient whether he or she perceives the additional light on that side. A verbal acknowledgment or a reflex contraction of the lids indicates light perception.

If the patient is able to exhibit a greater degree of compliance, the examiner may ask the patient to count fingers that are held at varying distances. The maximum distance at which these fingers can be counted should be noted on the chart (e.g., counting fingers at 4 ft). If the patient cannot stand but can identify letters or numbers, a commercially available near visual acuity card or any other reading material can be used to assess the quality of near vision. Very few injuries cause abnormal distance vision with preservation of near vision. Therefore, normal near vision usually indicates that the patient has not sustained a significant ocular injury. If the patient is able to comply, the examiner should obtain a visual acuity using a distance chart (see Chapter 131 Ophthalmic Emergencies).

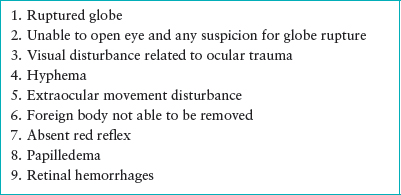

TABLE 122.1

INDICATIONS FOR EMERGENT CONSULTATION WITH AN OPHTHALMOLOGIST

If a patient demonstrates poor vision in the traumatized eye, the clinician can readily establish whether this deficit is related to the trauma or uncorrected refractive error using the pinhole test. When a person looks through a pinhole and experiences improvement in performance on visual acuity testing, he or she must have an uncorrected refractive error as the cause of the initially tested poor vision. If the visual deficit is related to the trauma, an ophthalmologist should be consulted. The urgency of evaluation will depend on the mechanism of injury and other physical examination findings.

2. Inspect the Periorbital Tissues and Eyelids Thoroughly

The periorbital tissues and eyelids should be carefully examined for ecchymosis, laceration, deformity, swelling, tenderness, and ptosis. Palpation of the orbital bones should be performed to assess for tenderness, deformity, or step-off that may suggest orbital fracture. If crepitus is present, it may be indicative of a fracture communicating with a sinus. Laceration in the periorbital tissue should be assessed for fat prolapse, which suggests communication with the orbital compartment and need for ophthalmology consultation. Examine sensation to evaluate for infraorbital or supraorbital nerve injury secondary to laceration or blunt trauma. For eyelid lacerations, careful attention should be paid to the location of the laceration and the depth of the wound. The eyelid should be inverted to evaluate for subconjunctival involvement, indicating that the laceration may be a full-thickness, complete perforation. Further, lacerations in close proximity to the medial canthus should prompt ophthalmology consultation for evaluation of the lacrimal duct system.

3. Open the Eyelids

If the eye has been traumatized such that the patient is unable to voluntarily open the eyelids, attempts should be made to assist the patient in doing so. A warm compress may be gently applied to the eyelashes to loosen any crust or discharge that may be holding the eyelashes together. When opening the eyelids, avoid pressure on the eyeball, which might lead to extrusion of intraocular contents via an underlying ruptured globe. The examiner’s thumbs can be placed on the supraorbital and infraorbital ridges while exerting pressure against the underlying bone, and then pulled away from each other such that the eyelids are separated (Fig. 122.1). If the eyeball cannot be readily viewed using these techniques, it is safer to refer the patient for an ophthalmology consultation. Risking the use of a speculum or retractor may upset the patient and contribute to disruption of intraocular contents if the globe is ruptured. Even the ophthalmologist may choose to avoid such attempts and proceed directly to an examination under anesthesia if the risk of ruptured globe is believed to be high.

FIGURE 122.1 Opening swollen eyelids manually from the superior and inferior orbital rims.

4. Check the Red Reflex

Absence of the red reflex indicates possible corneal scar or hemorrhage within the anterior chamber or vitreous. An abnormal red reflex requires emergent ophthalmology consultation.

5. Evaluate the Pupils and the Extraocular Movements

Evaluate for pain or limitation of movement of the eye, which may suggest muscle entrapment, nerve palsy, or retrobulbar hemorrhage. Examine for symmetric shape and size of the pupil, as well as responsiveness to direct and consensual light exposure. The presence of an afferent pupillary defect suggests the possibility of serious eye injury. This can be tested with the swinging flashlight test (see Chapter 24 Eye: Unequal Pupils).

6. Evaluate the Anterior Surface of the Eye

Inspect the conjunctiva and sclera for hemorrhage, trauma, or foreign body. Examine the anterior chamber for grossly visible layered blood. Slit lamp examination, preferably by an ophthalmologist, is required for evaluation for microhyphema.

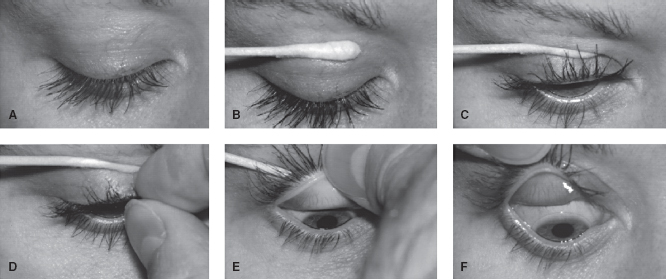

FIGURE 122.2 Upper lid eversion. Note that patient is looking down throughout procedure. In frame C, the swab is being rolled clockwise to engage skin and indirectly lift lash line. In frame E, the swab is being pushed downward as the examiner lifts the lashes upward in the opposite direction. In F, note that patient is wearing a contact lens.

Once a ruptured globe and a hyphema are ruled out, the administration of topical anesthetic should be considered. A drop of either proparacaine 0.5% or tetracaine 0.5% may have both diagnostic and temporary therapeutic usefulness. Any patient who is made more comfortable by the instillation of topical anesthetics must have an ocular surface problem (conjunctiva or cornea) as the cause of pain. The child who is crying and refusing to open the eyes may be compliant just a few minutes after the instillation of a topical anesthetic. Topical fluorescein is used as a diagnostic agent to stain the affected area in order to evaluate for corneal abrasions. Fluorescein is available as impregnated paper strips and as a solution combined with a topical anesthetic. When strips are used, they must be wet with either saline or topical anesthestic before instillation. Otherwise, the strip itself may cause a corneal abrasion. Fluorescein, which is orange, fluoresces yellow–green when exposed to blue light. The examiner can view through the direct ophthalmoscope, or a Wood’s or Burton lamp may be used. If the staining pattern reveals one or more vertical linear abrasions, the examiner should suspect the presence of a retained foreign body under the upper lid. This foreign body may be viewed by upper lid eversion (Fig. 122.2).

7. Perform Direct Ophthalmoscopy to Evaluate for Papilledema or Retinal Hemorrhages

If either is noted, emergency consultation with ophthalmology is required. Pharmacologic dilation of the pupil may be used to assist in evaluating the posterior portion of the eye (Table 122.2).

Consider Bedside Ultrasound

Literature describing the use of emergency bedside ultrasound as an adjunct to the physical examination for the evaluation of ocular foreign body, retinal hemorrhage, papilledema, and retro bulbar hematoma is emerging.

RUPTURED GLOBE

CLINICAL PEARLS AND PITFALLS

• In order to avoid extrusion of globe contents, globe rupture requires rapid recognition and emergent evaluation by an ophthalmologist.

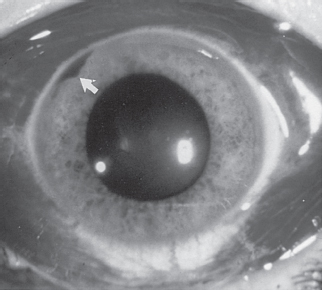

• Clinical findings include tear drop pupil, 360-degree subconjunctival hemorrhage, or enophthalmos (Fig. 122.3).

• If any of the above is present, immediately place an eye shield and minimize disturbing the child.

Current Evidence

Current literature related to globe rupture in children establishes that the visual prognosis is unfortunately often very poor. The following factors seem to be most predictive of poor visual outcome: blunt injury or injury resulting from a gun, young age, large wounds, wounds involving the sclera and associated injuries such as hyphema, vitreous hemorrhage, or retinal detachment. Prompt recognition and immediate referral to an ophthalmologist, ideally one with pediatric expertise, is the accepted standard of care.

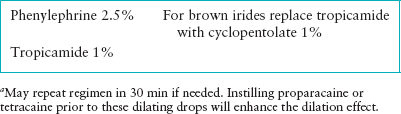

TABLE 122.2

EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT OCULAR DILATING REGIMENa

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree