Chapter 43 Obstetric Trauma

Epidemiology and Priorities of Care

Five to ten percent of gravid women will sustain an injury for which they seek medical care.1,2 Fortunately, most cases involve minor or moderate trauma, but life-threatening injuries complicate 3 in 1000 pregnancies.3 As is true for nonpregnant women in their childbearing years, motor vehicle crashes are the primary mechanism of maternofetal trauma for pregnant women as well. Falls are the second most common cause of injury in pregnant patients.1,2 Pregnancy is a time of increased interpersonal stress, which puts women at risk for abuse. The frequency of intimate partner violence during pregnancy is difficult to establish but has been estimated to be between 1.2% and 24%.4 Following major trauma, the obstetric patient has about the same mortality rate as a nonpregnant woman with comparable wounds.5 However, the vulnerable fetus is five to seven times more likely to die from an injury than is its mother.1

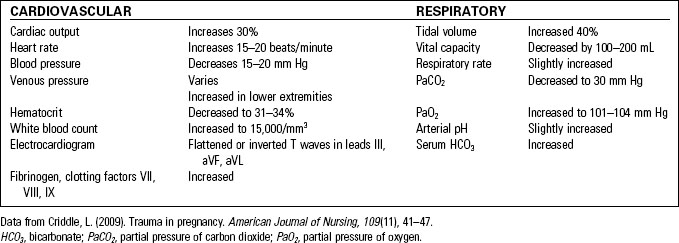

Care of the gravid trauma patient is complicated by the normal physiologic changes of pregnancy (Table 43-1) and by the presence of a second patient, the fetus. Pregnancy should never be permitted to divert attention from the rapid identification and appropriate management of maternal injuries.6 Vigorous maternal resuscitation remains the initial care priority and provides the fetus with the best possible chance of survival. Virtually all diagnostic procedures and interventions routinely employed in the care of the trauma patient are equally appropriate for management of the pregnant patient, with the addition of a few diagnostic procedures, modifications, and simple safety measures.

Assessment of the Obstetric Trauma Patient

Primary Assessment

The primary assessment of the pregnant trauma patient is conducted in the same manner and sequence as that of any other patient (see Chapter 35, Assessment and Stabilization of the Trauma Patient). Evaluation of airway, breathing, and circulation occurs simultaneously with interventions when a potentially life-threatening condition is identified. Importantly, the changes of pregnancy can mask normal physiologic responses to trauma, and these alterations must be considered carefully when managing the gravid patient. Table 43-2 summarizes the effects of these changes on the traumatized gravid patient.

TABLE 43-2 THE IMPACT OF NORMAL PHYSIOLOGIC CHANGES OF PREGNANCY ON THE TRAUMA PATIENT

HCO3, bicarbonate; PaCO2, partial pressure of carbon dioxide; PaO2, partial pressure of oxygen.

Data from Criddle, L. (2009). Trauma in pregnancy. American Journal of Nursing, 109(11), 41–47.

Airway and Breathing

• Decreased functional residual capacity and increased oxygen demands leave the pregnant patient vulnerable to hypoxia, especially during endotracheal intubation.6

• Maternal oxygen supplementation is the only effective way to improve fetal oxygen levels.5 The normal fetal PaO2 is only 32 mm Hg, so any drop from this already marginal level is poorly tolerated by the fetus.

• Once the patient’s spine has been cleared, raise the head of her bed to reduce diaphragm compression by the gravid uterus.

Circulation

• Mild hypotension (systolic blood pressure <100 mm Hg) and heart rate elevation (>100 beats per minute) are expected findings during pregnancy.2,6

• Central venous pressure is unaffected by pregnancy (except during delivery) and therefore serves as an indicator of maternal volume status.7

• A dramatic increase in circulating volume (starting at the tenth week of pregnancy) provides a significant maternal buffer against shock but masks gradual blood losses of 30% to 35% (approximately 1500 mL) or the acute loss of 10% to 15%.4

• As a result of shunting blood from the fetus, placenta, and uterus, signs of hemorrhage in the pregnant patient are often absent until volume deficits are severe.6,8

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree