Obstetric and Fertility Patients

Any critical illness may complicate pregnancy, or the postpartum period; especially sepsis and thromboembolic disease. Pregnancy-related illnesses may also require critical care intervention, including: pre-eclampsia and eclampsia, the HELLP syndrome, major haemorrhage, and anaphylactoid syndrome of pregnancy (amniotic fluid embolism). As with any critical illness, life-threatening problems are identified and treated first.

Fetal well-being relies upon successful maternal resuscitation. Treating the maternal critical illness takes precedence, both in terms of investigations and therapies required. Occasionally it may be necessary to deliver the fetus so as to optimize maternal resuscitation (usually only after 20 weeks as caval compression becomes significant from this gestation).

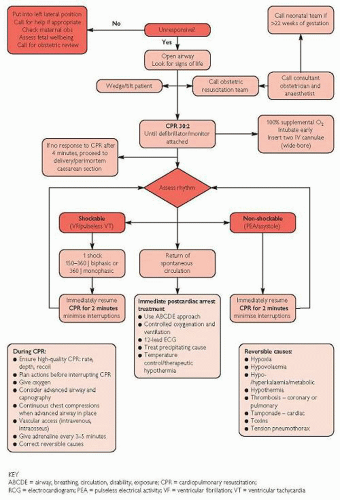

In cardiac arrests, emergency Caesarean section should take place alongside CPR.

Assessment (physiological changes of pregnancy)

The physiological changes that occur in pregnancy must be considered when assessing and treating pregnant women, these are:

Cardiovascular:

Plasma volume increases steadily up to 34 weeks’ gestation, in late pregnancy a haematocrit of 30-35% is not uncommon

Significant blood loss may occur without apparent maternal compromise (fetal distress may still occur)

Maternal heart rate may be ↑ by 25% in late pregnancy with a resultant increase in cardiac output of up to 1.5 L/minute

Supine positioning reduces venous return and cardiac output in the second half of pregnancy due to significant aorto-caval compression

Blood pressure typically falls by 5-15 mmHg during the 2nd trimester, returning to normal levels in the 3rd trimester

Respiratory:

Inspiratory capacity increases, FRC decreases; overall respiratory reserve reduces with pregnancy

Minute volume increases with ↑ tidal volume, leading to hypocapnia (PaCO2 ˜4 kPa) and compensated respiratory alkalosis

Oxygen consumption increases during pregnancy which, combined with the decrease in FRC, leads to rapid desaturation in the event of significant airway/breathing difficulties

Renal:

Glomerular filtration rate and renal plasma flow increase during pregnancy; serum urea and creatinine levels decrease (by up to 50% of normal)

GI tract:

Gastric emptying is delayed leading to ↑ risk of aspiration

Drug handling:

Maternal drug handling may be altered by changes occurring in pregnancy (e.g. serum albumin levels fall to levels of 20-30 g/L)

Teratogenic/harmful effects of drugs to the fetus must be considered at different stages of the pregnancy

Immediate management

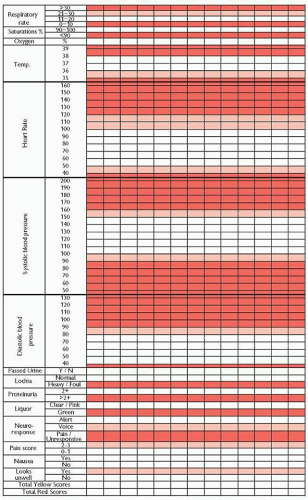

The use of an early warning scoring system, modified for obstetric patients, may facilitate the early detection of critical illness (Fig. 13.1;  p.428).

p.428).

p.428).

p.428).A multidisciplinary approach should be adopted with input from senior critical care/anaesthetic, obstetric, and midwifery disciplines.

Give O2 and support airway, breathing, and circulation as required.

If endotracheal intubation is required a rapid sequence intubation will be needed to minimize the risk of aspiration:

If endotracheal intubation is becoming increasing likely consider giving prophylactic ranitidine 150 mg PO, or equivalent (sodium citrate 30 ml PO can be used but may increase maternal nausea)

The incidence of difficult intubation increases in late pregnancy, especially in patients with pre-eclampsia; immediate availability of intubation adjuncts and familiarization with difficult airway protocols is required ( p.24)

p.24)

Rapid desaturation at induction is likely (mentioned earlier)

Mechanical ventilation may be difficult in heavily pregnant individuals; PEEP will be required to avoid further loss of FRC.

Aggressive fluid resuscitation and/or inotropes may be required:

In a pregnant patient a right-sided wedge, or even lateral positioning, will decrease the effects of aorto-caval compression (even in the early stages of pregnancy)

Manual displacement of the uterus may useful in an emergency

In cases of critical illness where pre-term delivery (23-34 weeks) is likely to occur, maternal steroids may improve fetal lung function post delivery (2 doses of betamethasone 12 mg 24 hours apart).

Further management

The incidence of thrombotic events increases in pregnancy, thromboprophylaxis should be instituted where possible.

It may be possible to facilitate the baby visiting the mother whilst she is in a critical care environment; this should be encouraged.

Breastfeeding is more likely to succeed if established early, and where appropriate it should be encouraged within critical care.

Drugs which are expressed in breast milk should be avoided if possible.

Routine pre- or postpartum examinations by obstetricians or midwives should still be conducted in patients in critical care settings.

Anti-D Rhesus immunization should be given to at-risk mothers.

Pitfalls/difficult situations

Consider the possibility of epidural complications or local anaesthetic toxicity in the differential diagnosis.

The management of patients with severe coexisting disease, particularly congenital cardiac abnormalities, will require specialist advice.

Fig. 13.1 Obstetric early warning scoring system. Contact doctor for early intervention if patient triggers 1 red or 2 pink scores at any one time.

Prophylaxis against potentially severe complications (e.g. anti-epileptic medications) should not be withheld unless absolutely necessary.

If delivery is expected in a critical care patient paediatric support will be required to assess and resuscitate the new-born.

Further reading

Neligan PJ, et al. Clinical review: special populations – critical illness and pregnancy. Crit Care 2011; 15: 227.

RCOG. Antenatal corticosteroids to reduce neonatal morbidity and mortality. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, Green-top Guideline No. 7, 2010.

RCOG. The use of anti-D immunoglobulin for Rhesus D prophylaxis. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, Green-top Guideline No. 22, 2011.

RCOG. Reducing the risk of thrombosis and embolism during pregnancy and the puerperium. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, Green-top Guideline No. 37a, 2009.

RCOG. Maternal collapse in pregnancy and the puerperium. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, Green-top Guideline No. 56, 2011.

Singh S, et al. A validation study of the CEMACH recommended modified early obstetric warning system (MEOWS). Anaesthesia 2012; 67: 12-18.

Pre-eclampsia (or pre-eclamptic toxaemia, PET) occurs after the 20th week of pregnancy, and can occur into the postpartum period. It is defined as pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH) with a systolic BP >140 mmHg and/or diastolic BP >90 mmHg (on 2 separate occasions); with proteinuria of 0.3 g in a 24-hour period.

Severe pre-eclampsia is defined as pre-eclampsia with a systolic BP >160 mmHg or diastolic BP >110 mmHg and/or symptoms (e.g. altered neurology), and/or biochemical/haematological impairment. Death occurs as a result of CVA, hepatic failure, cardiac failure, or pulmonary complications.

Eclampsia is the occurrence of major seizure activity in the presence of pre-eclampsia (38% occur antepartum, 18% intrapartum, 44% postpartum). It may occur before the signs of hypertension or proteinuria.

Causes

Risk factors for pre-eclampsia include:

First pregnancy.

Pre-eclampsia in a previous pregnancy.

Diastolic BP >80 mmHg at booking.

Obesity.

Increasing maternal age.

Multiple pregnancies or polyhydramnios.

Underlying medical conditions:

Previous hypertension

Diabetes mellitus

Renal disease

Autoimmune disease such as SLE or antiphospholipid antibodies

Presentation and assessment

Pre-eclampsia, even when severe, may be asymptomatic and only discovered by routine blood pressure screening, or when complications such as eclampsia occur.

Signs and symptoms, when they occur, consist of:

Neurological:

Headache and/or visual disturbance (cerebral oedema)

Hyper-reflexia/clonus (≥3 beats)

Seizures

Papilloedema

Respiratory:

Dyspnoea on exertion

Pulmonary oedema

Cardiovascular: hypertension (>140/90 mmHg).

GI:

Nausea and vomiting;

Epigastric discomfort (hepatic engorgement/ischaemia)

Renal: proteinuria, marked oliguria (often <0.25 ml/kg/hour).

General:

Peripheral oedema

Facial and laryngeal oedema (this may result in difficulty in endotracheal intubation)

Investigations

FBC (thrombocytopaenia may be seen, platelets <100 × 109/L).

Blood film (if TTP suspected).

Coagulation studies, including fibrinogen (DIC may occur with raised PT and APTT, thrombocytopaenia, hypofibrinogenaemia).

U&Es (may be deranged as AKI can occur, a creatinine >80 µmol/L is likely to be abnormal, depending on maternal size).

Serum glucose (hypo/hyperglycaemia may be present).

Serum urate is no longer recommended as a diagnostic test but may still be tested in some centres (previously thought to be associated with pre-eclampsia: >10 × the gestational age in weeks in µmol/L, or >360 µmol/L, or >6 mg/dL).

Urinalysis, options include:

Urine dipstick (proteinuria: ≥++ seen; severe proteinuria: ≥+++ seen); ≥+ proteinuria seen requires further investigation

Spot protein: creatinine ratio (PCR) >30 mg/mmol

24-hour collection (proteinuria: ≥0.3 g/24 hours; severe proteinuria: >1 g/24 hours)

Blood, urine, and sputum cultures (if infection is suspected).

US of the fetus, to examine for fetal well-being.

Differential diagnoses

Seizures or altered neurology:

Epilepsy (prior history of seizures)

Encephalitis/meningitis (signs of sepsis)

Hypertension:

Pre-existing hypertension (prior history)

Pain/agitation

Immediate management

A multidisciplinary approach should be adopted with input from senior critical care/anaesthetic, obstetric, and midwifery disciplines

Give O2 and support airway, breathing, and circulation as required.

Overall aims include stabilization of BP, prevention of eclamptic seizures, and opportune delivery of the baby.

Hypertension treatment

The aim should be to reduce diastolic BP to around 90-100 mmHg, precipitous drops in BP should be avoided.

There is no consensus as to what constitutes first- or second-line therapy, a reasonable approach might be:

First-line treatment: labetalol 200 mg PO, repeated after 30 minutes if required; if oral labetalol is ineffective consider labetalol 50 mg IV repeated every 5 minutes to a maximum of 200 mg, followed by infusion at 5-50 mg/hour

Second-line: if labetalol is not tolerated or contraindicated (e.g. in asthmatics) give nifedipine 10 mg PO, which can be repeated after 30 minutes if required (nifedipine should not be given sublingually)

Third-line: hydralazine 5-10 mg by slow IV bolus, repeated after 15 minutes, followed by an infusion at 5-15 mg/hour (consider a bolus of ≤500 ml crystalloid before, or at the same time as hydralazine given in the antenatal period)

Atenolol, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and diuretics should be avoided

Treatment and/or prevention of eclamptic seizures

Magnesium sulphate IV 4 g (16 mmol MgSO4) over 5-10 minutes, followed by an infusion of 1 g/hour (4 mmol/hour) for at least 24 hours:

A further dose of magnesium sulphate 2 g (8 mmol MgSO4) over 15-20 minutes can be given if further seizures occur; or the infusion rate ↑ to 2 g/hour

Close observation for evidence of magnesium toxicity is essential (see p.224).

p.224).

Second-line eclampsia treatments are only rarely required if BP control and magnesium have been used, but may include:

Induction of anaesthesia with endotracheal intubation and ventilation (the presence of upper airway oedema suggests difficult intubation will be more likely)

The definitive treatment for severe pre-eclampsia/eclampsia is delivery of the baby:

The decision to deliver must weigh up the needs of the mother against the maturity of the baby

Seizures and other symptoms should be controlled prior to proceeding to delivery/Caesarean section if possible

Patients may be transferred to critical care for enhanced monitoring and vital organ support pre- or post-delivery

Further management

The role of CVP monitoring is unclear, it can aid fluid management, but is not always required if urine output/fluid balance is strictly monitored; it is more difficult in the presence of agitation, dyspnoea, oedema, and coagulopathy.

There is no evidence of benefit from fluid expansion and a fluid restriction regimen is associated with good maternal outcome:

Limit maintenance fluids to 80 ml/hour unless there are other ongoing fluid losses, such as haemorrhage

There is no evidence that maintenance of a specific urine output is important to prevent renal failure (which is rare).

Pitfalls/difficult situations

Endotracheal intubation may cause a profound hypertensive surge; short-acting IV

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

p.161

p.161 p.427

p.427