Section VI Paula Snyder The performance of a thorough neurologic history and physical examination is of paramount importance and will enable the neuroscience team to diagnose the patient with neurologic disease rapidly and will expedite definitive treatment. An accurate history may be difficult to obtain because of the patient’s neurologic status. Family members or a significant other may need to be called on for the patient’s history. Old charts and records may also need to be consulted. A detailed history should include the chief complaint, a history of the present illness, and a past medical history. A chief complaint includes a brief statement or response to the question, What brought you to the hospital today? A history of the present illness includes a description of the signs and symptoms, onset, location, severity, duration, frequency, and aggravating and/or alleviating factors. The past medical history should include the patient’s medical and medication history, substance use and abuse, sexual history, and family and social history. The neurologic history should include assessment of pain, headaches, seizures, and changes in eating or sleeping patterns. It should attempt to derive answers to the following: It is important to ascertain the mechanism of injury in trauma patients. Acceleration-deceleration, rotation, flexion-extension, and axial loading may cause specific brain or spinal cord injuries. These injuries may include coup/contrecoup brain injury, diffuse axonal injury, and spinal injuries. “Down” times and extrication times are also important. When did the trauma occur? How long was it before medical assistance was given? Discerning the patient’s hypoxia or hypotension at the scene of the injury may give clues to its severity or long-term prognosis. Finding out if there was vomit at the scene, for example, or if the patient had gurgling respirations can alert you to whether or not the patient has been predisposed to respiratory complications such as aspiration pneumonia. The mental status exam is a brief assessment to test higher levels of cortical function. Asking simple questions regarding persons, places, time, and reason assesses orientation and attention. Is the patient able to answer questions during the interview, or is he or she distracted, needing to be redirected frequently? Assessment of remote and recent memory is tested with such questions as, What did you have for breakfast? and, Where did you grow up? or by asking the patient to recall three words told to him or her earlier in the exam. Have the patient name objects, such as a pen, paper clip, and comb, and their function or purpose. Have the patient read, write, and copy figures. Test abstract reasoning and judgment by asking the relationship between word pairs (cat-dog, comb-brush, hot-cold) or the meaning of a saying or proverb (e.g., “A stitch in time saves nine”). Refer the patient for neuropsychological evaluation if deficits are present. The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) is the most frequently used tool to assess the level of consciousness (LOC). The patient is scored on a scale of 3 to 15 in three areas based on his or her best responses (Table 29–1).1

Nursing Issues

29

Nursing Issues

Obtaining a Neurologic History

Obtaining a Neurologic History

Components of the Neurologic Exam

Components of the Neurologic Exam

Mental Status

Level of Consciousness

| Eye Opening | Verbal Response | Motor Response |

| 4: opens eyes spontaneously | 5: oriented | 6: obeys commands |

| 3: opens eyes to sound | 4: confused | 5: localizes to pain |

| 2: opens eyes to pain | 3: inappropriate words | 4: withdraws to pain |

| 1: no eye opening | 2: incomprehensible sounds | 3: flexes/decorticates to pain |

| 1: nonverbal | 2: extends/decerebrates to pain | |

| 1: no response to pain |

The patient should be approached quietly (not silently) when assessing for spontaneous eye opening. Several spheres should be checked when assessing for orientation (person, place, time, and reason). The patient should not be overly coached in his or her answers or motor responses. Time should be allowed for the patient to answer questions and follow commands. The same command should be simply repeated to avoid confusing the patient. When assessing pain response, central pain stimulation should be used. Nail bed pressure may elicit a spinal reflex and be confused with withdrawal by the examiner. A purposeful response can be differentiated from flexion by observing if the patient crosses the midline in response to pain.

A patient who is awake, alert, oriented, and obeying commands receives a GCS of 15. A patient who is completely unresponsive to painful stimulation receives a GCS of 3. Patients with a GCS score of 8 or less are comatose1 and are at high risk for respiratory compromise. These patients are usually intubated and cared for in the neurosurgical intensive care unit (NICU).

Care should be taken when using one-word descriptions of a patient’s LOC. It is best to describe the response to stimulation and the kind of stimulation needed to elicit the response (Table 29–2).

| Good | Better |

| Alert | Responds immediately |

| Confused | Disoriented to person/time/place/reason |

| Lethargic | Requires increased or frequent stimuli to be awakened |

| Obtunded | Minimal response to stimuli; one-word answers |

| Stuporous | Aroused only by vigorous, continuous stimuli |

| Comatose | No voluntary, purposeful response |

| Pupil | Reaction | Possible Causes |

| Pinpoint | None or minimal | Pontine injury or narcotic overdose |

| Midposition | Reactive | Normal response |

| Nonreactive | Midbrain injury | |

| Dilated | Reactive | Stimulant use, autonomic dysfunction |

| Sluggish/nonreactive | Unilateral: pressure, swelling, hemorrhage, tumor, herniation, aneurysm, or orbital trauma Bilateral: brain anoxia, herniation, or death |

Pupillary Assessment

Pupillary response is a function of the autonomic nervous system via cranial nerve (CN) III. Parasympathetic and sympathetic control causes the pupils to constrict and dilate. Before beginning the pupil exam, dim the room lights to prevent missing a minimal reaction.

The following steps are followed in a pupillary assessment:

- Direct light reflex: Shine the light directly into one eye. The pupil should immediately constrict to light. When the light is removed, the pupil should immediately dilate.

- Consensual response: Shine the light in one eye while watching for constriction of the opposite pupil. Observe for dilation when the light is removed (Table 29–3).

Speech and Language Assessment

Communication incorporates four functions: the ability to listen, read, speak, and write.1 Disturbances in these functions can be categorized as shown in Table 29–4.

| Type | Description |

| Aphasia | Inability to speak due to disturbances in the dominant hemisphere |

| Dysphasia | Difficulty in communication |

| Expressive aphasia (Broca’s) | Inability to correctly form thoughts and communicate information; comprehension is relatively preserved |

| Receptive aphasia (Wernicke’s) | Inability to correctly comprehend written (alexia) or verbal language |

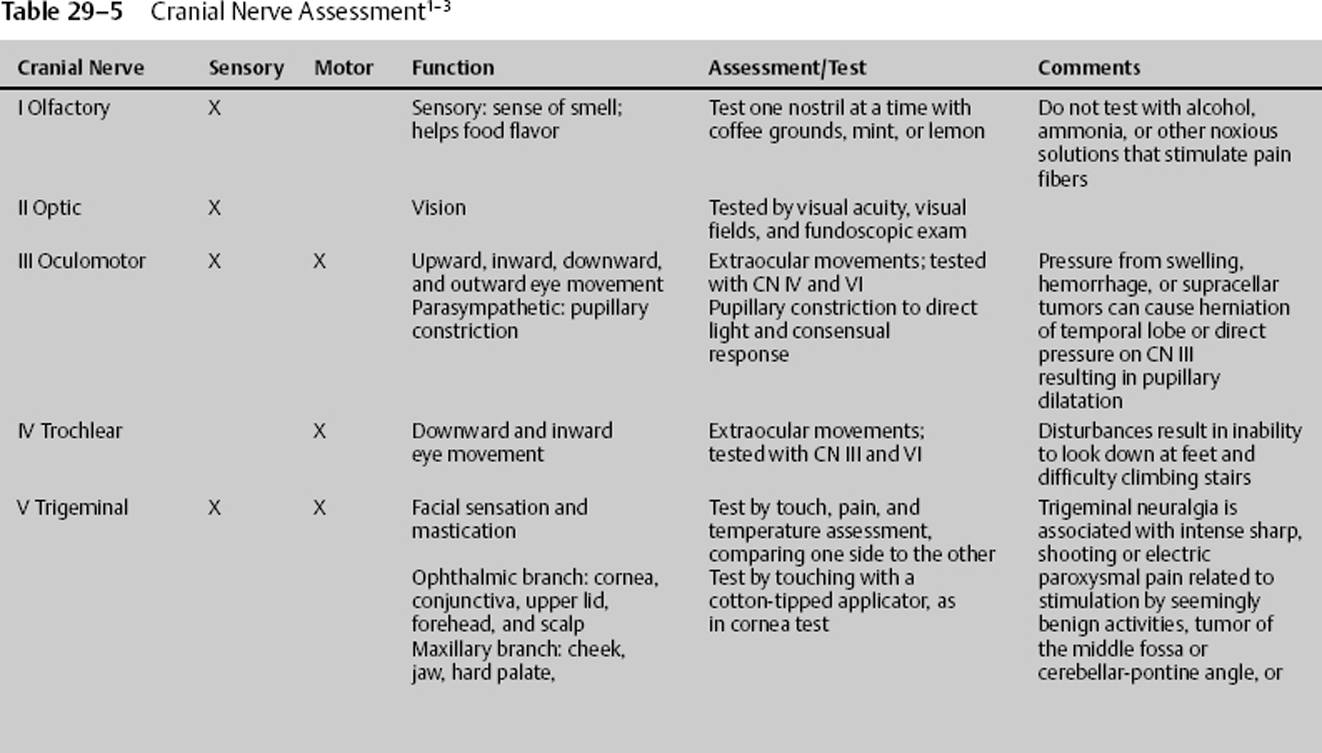

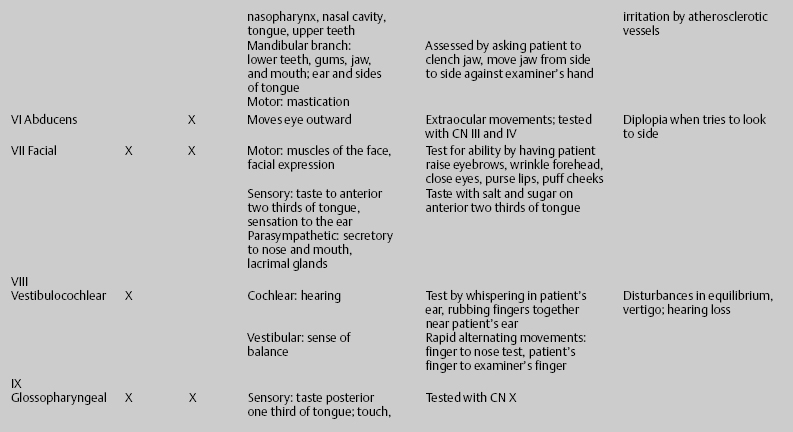

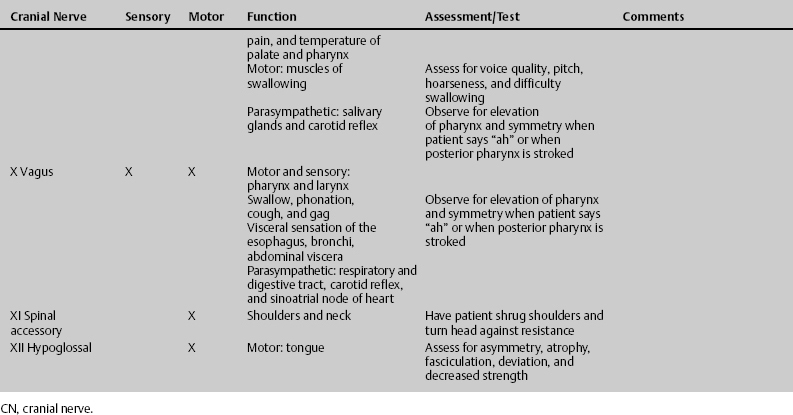

Cranial Nerve Assessment

There are 12 pairs of cranial nerves. The cranial nerves are numbered I to XII according to the order in which their nuclei connect to the brain (Table 29–5).

Motor Assessment

Motor assessment includes a general assessment of

- Symmetry

- Muscle bulk

- Atrophy

- Tone: spasticity, rigidity, and flaccidity

- Strength

- Reflexes

Muscle strength is graded on a scale of 0 to 5, as shown in Table 29–6.

The nurse should be vigilant in his or her assessments. Frequent neurologic assessment by the bedside nurse is imperative to detect subtle changes in LOC. It is helpful if nurses who are changing shifts assess the patient’s GCS, pupils, and a brief focused motor and sensory exam together. This will help decrease interrater variability and prevent missing significant neurologic changes.

Vital Signs

Vital signs should be documented at least hourly. Careful attention should be paid to trends or gradual changes in vital signs and neurologic responses. These changes may not be noticeable on an hourly basis, but they are significant over time. A decrease in GCS of 2 points is significant and should be reported to the attending physician, as it may signal increasing intracranial pressure (ICP) or tissue hypoxia. Other hourly observations should include pupillary responses, extraocular movements, focused motor and sensory exam, strict intake and output, blood pressure, heart rate and rhythm, temperature, central venous pressure, and pulmonary artery pressures when available.

Changes in vital signs are often late; earlier signs of neurologic deterioration are increasing headaches, agitation, nausea/vomiting, and a sense of impending doom. You may also see cranial nerve changes, such as facial drooping or asymmetry, dysconjugate gaze, and pupillary changes. There may be increasing pronator drift, muscle weakness, and posturing. Brainstem reflexes (gag, cough, and corneal reflexes) should be noted upon initial assessment and during interim assessments, every 4 hours or more often as indicated. Seizure may also indicate neurologic deterioration. Acute changes in LOC may be a sign of silent seizure and should be evaluated by electroencephalogram (EEG).

| Grade | Character |

| 0 | No muscle contraction |

| 1 | Trace contraction |

| 2 | Movement with gravity eliminated |

| 3 | Movement against gravity |

| 4− | Slight resistance |

| 4 | Moderate resistance |

| 4+ | Strong resistance |

| 5 | Normal/full strength |

Cushing’s Response

Cushing’s response is the body’s reaction to increased ICP and resulting cerebral ischemia. It is characterized by bradycardia, elevated systolic blood pressure (SBP), respiratory irregularities, and widening pulse pressure. As the pressure within the brain nears the cerebral arterial pressure, the vagal and sympathetic nerves are stimulated, resulting in increased cardiac output, bradycardia, and shunting of blood flow from other body organs to the brain. Arterial blood pressure rises in an attempt to restore cerebral perfusion. Cushing’s response is a late sign of increased ICP and is associated with irreversible brain damage. It may be transient or not be present in all patients experiencing neurologic deterioration.1

Patients who have suffered a direct injury or bleed to the brainstem may exhibit the same signs and symptoms found in increased ICP with normal ICP.2 Brainstem injuries carry a poor prognosis for recovery.1

Blood Pressure

Hypotension associated with head injury is usually a sign of a terminal event. In the NICU patient with signs of life, it is probably attributable to another cause, and it should be evaluated aggressively. In trauma patients, it may be caused by bleeding in the chest, abdomen, or pelvis, or associated with blood loss in long bone fractures, or it may be a result of spinal cord injury (SCI). Hypotension in high SCI is usually accompanied by bradycardia. Hypertension not associated with increased ICP may be caused by pain, fear, and anxiety. The patient may also have a known or unknown history of hypertension.

Heart Rate

Tachycardia in the neurosurgical or head-injured patient may be a result of injury to the hypothalamus or may signify a terminal neurologic event, such as brain herniation or death. Other causes of elevated heart rate may include fever, dehydration, hypotension, and shock. Agitation and pain may also cause tachycardia. A catecholamine “storm,” or stress response in a head injury, may also cause a high heart rate.1 The nurse must be a good detective when looking for the root cause of tachycardias. Just remember to keep the patient calm and comfortable.

Respirations

Respiratory changes may not be as evident in the NICU patient, who often comes to the unit already intubated on mechanical ventilation. Changes can still be observed, though. Respirations may become rapid and deep, as in central neurogenic hyperventilation. This type of hyperventilation serves to lower ICP by lowering partial pressure of CO2 (PCO2), thus causing cerebral vasoconstriction, but it may worsen tissue hypoxia. Cheyne-Stokes respirations may precede cerebral herniation. Agonal respirations often occur when death is imminent. Rapid respirations may result from hypoxemia. Inadequate oxygenation of the brain will result in secondary brain injury in the NICU patient. Respiratory monitoring should include continuous assessment of oxygenation status to prevent hypoxemia. The routine O2 titration order “keep SpO2 [pulse oxygenation saturation] greater than 97%” will not ensure optimum brain tissue oxygenation. SpO2 and partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood (PaO2) should be correlated with arterial blood gases.

Temperature

Fever should be prevented and treated promptly if it occurs. Cerebral metabolism is increased ~10% with each degree of Celsius temperature. Increased O2 consumption results in brain tissue hypoxia and secondary brain injury.1 Hypothermia occurs frequently in SCI patients due to loss of autonomic function and thermoregulation. They are poikilothermic, meaning their temperature changes with environmental temperature changes. The room, therefore, must be kept at a constant temperature. Injury to the hypothalamus may also cause hypothermia. Cooling and/or warming measures should be employed as appropriate.2 Remember that steroid use may inhibit a patient’s ability to mount a fever in the face of infection.

Imaging

Imaging

It is better to get a computed tomography (CT) scan than to guess whether or not a patient is deteriorating or just waxing and waning. Generally speaking, if the patient does not look as good postop as he or she did preop, you probably need to rule out postop bleeding. Do not just chalk up a change in neurologic status to the patient’s being “sensitive” to anesthesia. Subdurals do reaccumulate, epidurals do rebleed, and hematomas can develop in postop hematoma cavities. There may be delayed bleeding in trauma or stroke patients. Be aware and report changes to the physician promptly.

Intracranial Pressure Monitoring

Intracranial Pressure Monitoring

ICP should be monitored in patients with a GCS of 3 to 8 via a ventricular catheter. Guidelines set forth by the Brain Trauma Foundation3 discuss the high chance of having increased ICP in patients with severe head injuries and with a GCS of 3 to 8 and intracranial findings on CT or GCS of 3 to 8 and two of the following: >40 years of age, posturing, or SBp < 90 mm Hg.3 Those patients with a GCS of 3 to 8 and not meeting the above criteria still risk having an increased ICP. Some of the benefits of ICP monitoring with a ventriculostomy include the following:

- Allows identification of elevated ICP before clinical signs and symptoms appear

- Allows drainage of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) to treat or prevent increased ICP

- Allows identification of the patient’s tolerance to routine nursing and medical procedures

- Allows judgment of the patient’s response to therapeutic measures, treatments, and medications

Whether you are using the traditional gold standard external transducer system or a fiberoptic catheter for ICP monitoring, remember that it is a potential source for contamination. Strict aseptic technique should be observed when handling and changing tubing and drainage bags. CSF output is monitored every 1 to 2 hours for amount, color, and clarity.

Nursing management of increased ICP is directed toward prevention and early identification of factors that precipitate increased ICP. The simplest maneuver to lower ICP is to increase venous drainage from the brain. The best way to do this is to elevate the head of the bed. Use the reverse Trendelenburg’s position for those patients in spinal precautions. Keep the head in the midline position, with minimal or no hip flexion. Prevent abdominal distention by maintaining patency of gastric tubes and by monitoring feedings for high gastric residuals. Titrate sedation to prevent agitation, but by the same token do not oversedate NICU patients. Oversedation can confound the neurologic assessment. Sedation should be held each shift and periodically during the day to allow for neurologic assessment as long as ICP is responsive to resedation.

Stimulation and Family Interaction

Stimulation and Family Interaction

How much stimulation is too much? Is the patient’s ICP and tissue oxygenation stable while family members are visiting? Watch what they are saying to the patient. Instruct them to speak positively to the patient, with encouraging words. Ask them to tell the patient about things that are important to him or her. Let the patient know that the children and pets are safe and well cared for. Warn the family against telling the patient to “fight,” as this may cause increased agitation in the patient. Instruct them not to ask questions when the patient is intubated and/or unable to speak, unless the patient is able to nod his or her head in response; even then, questions should be limited to “yes” “no” types. Music, taped voices of children, get well cards, and pictures may help with the patient’s recovery. A few personal items from home also may help comfort the patient.

Recruit the patient’s family members. Make them your allies. Teach them the basics of patient care, and involve them in their loved one’s daily routine. When the patient has a neurologic disease or injury, he or she is probably going to need family assistance for activities of daily living, at least on a short-term basis, if not for the long term. Teaching family members early will help in their transition to caregivers. An added benefit is that they will not be calling you to the bedside constantly because they are anxious about every gurgle or alarm. Families are often the best alternative to restraint use in agitated patients. However, you must first observe the interaction between the family members and the patient. Do they have a soothing effect on the patient? Are they responsible and attentive to the patient? If they are, you may be able to reduce restraint use while improving the patient’s comfort level.

Family members need some distraction when their loved one is in the hospital. After the patient has passed the critical phase of his or her NICU stay, it is a good time to ask the family to begin compiling a “memory book” for the patient. It should include clearly labeled photos of family members, friends, pets, home, cars, and anything else of importance to the patient. This will help the patient remember and/or relearn who was in his or her life and what his or her life was like.

Mobility

Mobility

It is important to mobilize the patient as soon as possible. Sit the patient up in bed as soon as you can get an okay from the physician. Let the patient dangle his or her legs from the bed. The longer a person lies on his or her back, the harder it will be to move him or her. Use elastic support hose, and change positions slowly to help prevent orthostatic hypotension. Abdominal binders may also be helpful in SCI patients. Involve physical therapists as soon as the patient has passed the initial critical phase of his or her hospitalization. In the meantime, turn the patient frequently (every 2 hours or more frequently). If the patient is on prolonged bed rest, suggest some form of rotational therapy bed.

Discharge Planning

Discharge Planning

References

- Barker E. Neuroscience Nursing: A Spectrum of Care. 2nd ed. St. Louis, MO: CV Mosby; 2002

- Hickey JV. The Clinical Practice of Neurological and Neurosurgical Nursing. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003

- Guidelines for the Management of Severe Traumatic Brain Injury. New York: Brain Trauma Foundation; 2000

- Hickey JV. The Clinical Practice of Neurological and Neurosurgical Nursing. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003

< div class='tao-gold-member'>