EPISTAXIS

Epistaxis occurs most frequently in children under 10 years old and in those over 70 years old.1 Local causes of epistaxis include digital trauma, a deviated septum, dry air exposure, rhinosinusitis, neoplasia, or chemical irritants such as inhaled corticosteroids or chronic nasal cannula oxygen use. Systemic factors that increase the risk of bleeding include chronic renal insufficiency, alcoholism, hypertension, vascular malformations such as hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, or any kind of coagulopathy, including warfarin administration, von Willebrand’s disease, or hemophilia.2

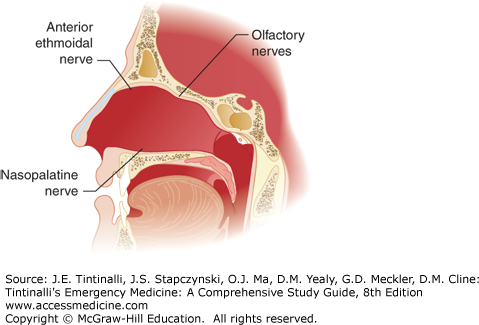

The superior labial branch of the facial artery joins the anterior ethmoidal and terminal branch of the sphenopalatine artery to form Kiesselbach plexus on the anterior nasal septum, which is the source of 90% of nosebleeds and can usually be visualized with anterior rhinoscopy (Figure 244-1). The most likely source for posterior bleeds is the sphenopalatine artery, which is a terminal division of the internal maxillary artery (branch of the external carotid system). Endoscopic or open surgical techniques are needed to visualize the vessel.2,3 Sensory innervation is detailed in Figure 244-2.

A directed history and physical examination is usually sufficient to identify the source of acute epistaxis. Ask about prior or recurrent epistaxis, duration and severity of the current episode, and laterality. Ask specifically about nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, warfarin, heparin, or aspirin use. Alcohol or cocaine abuse, trauma, prior head and neck procedures, and a personal and family history of coagulopathy should be assessed.

Make preparations for nasal examination and tamponade. The ED should have a preprepared, readily available epistaxis kit or cart. The kit should include a nasal speculum, bayonet forceps, headlamp, suction catheter, cotton pledgets, 0.05% oxymetazoline and 4% lidocaine solutions, silver nitrate swabs, and some combination of absorbable and nonabsorbable materials for anterior and posterior packing.

Assemble a good light source, suction, and a nasal speculum. Have the patient seated and in the “sniffing” position. The sniffing position is achieved by having the patient flex and extend the head while keeping the base of the nose straight ahead. With the patient in this position, brace the speculum by resting the index finger on the tip of the nose and insert the speculum with the handle parallel to the floor. Open the blades in a cephalad-to-caudad direction to visualize the bleeding site and facilitate the performance of direct hemostatic techniques.

Differentiating an anterior versus posterior source of bleeding is important for treatment and disposition; failure to identify the source of bleeding is associated with rebleeding and return for treatment.4 The division between anterior and posterior bleeding in the ED is often based on the ability to visualize the site of bleeding with a light source and a nasal speculum.5 Generally, the diagnosis of posterior hemorrhage is only made in the ED once measures to control anterior bleeding have failed. Clinical features suggestive of a posterior source include elderly patients with either inherited or acquired coagulopathy, a significant amount of hemorrhage visible in the posterior nasopharynx, hemorrhage from bilateral nares, or epistaxis uncontrolled with either anterior rhinoscopy or an anterior pack.6 Laboratory evaluation or other ancillary studies are not required unless management of comorbid illness requires it or the hemorrhage is poorly controlled. In the latter case, collect blood for CBC, type and cross-match, and coagulation studies if coagulopathy is suspected.

Initial ED management for epistaxis begins with a rapid primary survey addressing potential airway or hemodynamic compromise. Obtain IV access in patients with severe bleeding, and request cross-matched blood if there is hemodynamic instability. The need for transfusion is more common in patients with posterior epistaxis and those on anticoagulants.7 Reversal of coagulopathy with blood products can be considered based on clotting studies and individual patient context. Rapid reduction of blood pressure during an episode of acute epistaxis is generally not advised.8 For uncontrolled epistaxis requiring packing or surgical intervention, gentle reduction of persistent hypertension reduces hydrostatic pressure and thereby may aid clot formation.8

First, ask the patient to blow the nose to expel clots to prepare mucosa for topical vasoconstrictors. Instill a topical vasoconstrictor such as oxymetazoline or phenylephrine. The patient should lean forward in the “sniffing” position and pinch the soft nares between the thumb and the middle finger for a full 10 to 15 minutes, breathing through the mouth. If the patient is uncooperative, fashion a hands-free pressure device made from two tongue depressors that are taped together between halfway and two thirds of the way up the depressors. Place the device on the nose and leave it undisturbed for 10 to 15 minutes. These initial measures are often sufficient to achieve hemostasis and facilitate further examination by anterior rhinoscopy.

If two attempts at direct pressure have failed, chemical cauterization with silver nitrate is the next appropriate step for mild bleeding. Before cautery, anesthetize the nasal mucosa using three cotton pledgets soaked in a 1:1 mixture of 0.05% oxymetazoline and 4% lidocaine solution.2 Do not attempt chemical cautery unless the bleeding vessel is visualized. Electrical cautery should be left to the otolaryngologist due to the risk of septal perforation.

After visualizing the (anterior) bleeding site, silver nitrate sticks may be judiciously placed just proximal to the bleeding source on the anterior nasal septum. Silver nitrate requires a relatively bloodless field, as the chemical reaction leading to precipitation of silver metal and tissue coagulation cannot proceed in the setting of active hemorrhage due to washout of substrate. Once a relatively bloodless field is achieved, gently and briefly (a few seconds) apply silver nitrate directly to the bleeding site. Chemical cautery should never be attempted on both sides of the nasal septum. Subsequent attempts on the same side of the nasal septum should be separated by 4 to 6 weeks to avoid perforation.9

Thrombogenic foams and gels are a good option, and they may be considered after attempts at chemical cautery have failed and before insertion of nasal tampons. Gelfoam® and Surgicel® (oxidized cellulose) are effective hemostatic agents that can be placed simultaneously on visualized bleeding mucosa, and they are bioabsorbable, so removal is not needed. FloSeal®, a hemostatic gelatin matrix that is mixed in a syringe with thrombin and injected into the nasal cavity, may decrease episodes of rebleeding and the need for specialty follow-up compared to other agents.10 A 2013 randomized controlled trial involving 216 patients demonstrated that 5 mL of the injectable form of tranexamic acid, equal to 500 milligrams, applied topically to the nasal mucosa using a 15-cm piece of cotton pledget, stopped anterior epistaxis in 70% of patients, compared to a 31% success rate in those who received anterior packing alone.11 There were no adverse events. Topical use of injectable tranexamic acid may prove to be a valuable procoagulant.

Anterior nasal packing can be placed if direct pressure, vasoconstrictors, or chemical cautery are unsuccessful in controlling epistaxis and if thrombotic foams and gels are not available. A variety of nasal balloons or sponges are available, or an anterior pack created by layering ribbon gauze in the nasal cavity can be used.

Anterior epistaxis balloons (Rapid Rhino®) are easy to use and more comfortable for the patient than layered strip gauze or nasal sponges. Anterior epistaxis balloons are available in different lengths and are coated with cellulose or other materials that promote platelet aggregation. Soak the balloon with water, insert it gently along the floor of the nasal cavity, and inflate slowly with air until the bleeding stops. Stop inflation if the patient develops discomfort. Do not inflate with saline; if a saline-filled balloon ruptures, aspiration could result. Read specific insertion instructions for each product before use. If there is a drawstring at the distal end, tape the drawstring to the face to secure the balloon in place.

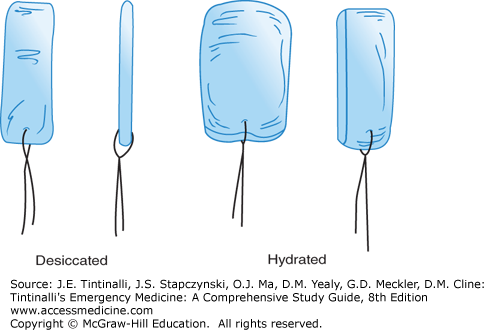

Preformed nasal tampons or sponges are made of synthetic material that expands after hydration (Figure 244-3). These devices are commercially available in 5- and 10-cm lengths, for anterior and posterior packing, respectively. One product is Merocel®, a compressed dehydrated polyvinyl acetate sponge. Coat the sponge with water-soluble antibiotic ointment and insert it gently along the floor of the nasal cavity. If the tampon has not expanded within 30 seconds of placement, gently irrigate it (while in place) with 5 mL of normal saline to promote expansion. An alternative method is to cut the Merocel® pack lengthwise in two equal halves, and coat each half with lubricating ointment. Insert the two halves parallel to each other and parallel with the nasal septum; irrigate each half with about 2 mL of normal saline. This method may provide better compression of septal bleeding.12 Whichever method is used, tape the drawstring to the face (Figure 244-3) to secure the tampon in place and prevent inadvertent aspiration. Merocel® nasal packs work effectively but sometimes cause more pain than balloons with removal.13

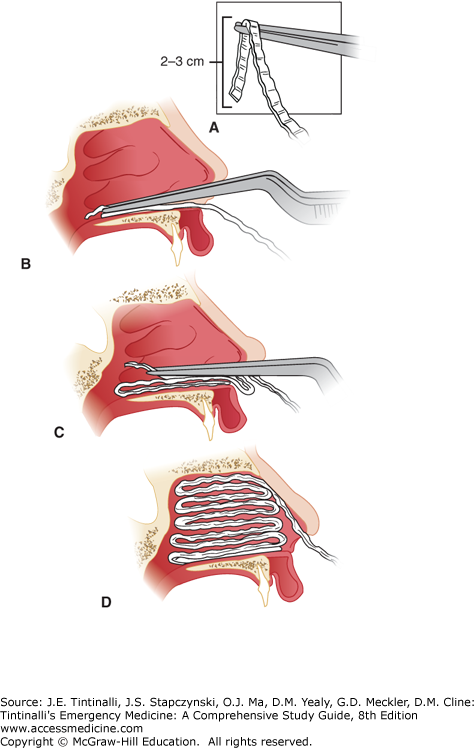

If the preceding devices are unavailable, ribbon gauze packing can be placed to control epistaxis (Figure 244-4).

FIGURE 244-4.

The key to placement of an anterior nasal pack that will control epistaxis adequately and stay in place is to lay the packing into the nasal cavity in an accordion-like manner so that part of each layer of packing lies anteriorly, preventing the gauze from falling posteriorly into the nasopharynx. A. The first layer of ¼-inch petrolatum-impregnated gauze strip is grasped approximately 2 to 3 cm from its end. B. The first layer is then placed on the floor of the nose through the nasal speculum (not pictured here). The bayonet forceps and nasal speculum are then withdrawn. C. The nasal speculum is reintroduced on top of the first layer of packing, and a second layer is placed in an identical manner. After several layers have been placed, it is often useful to reintroduce the bayonet forceps to push the previously placed packing down onto the floor of the nose, making it tighter and more secure. D. A complete anterior nasal pack can tamponade a bleeding point anywhere in the anterior nasal cavities and will stay in place until removed by the provider or patient.

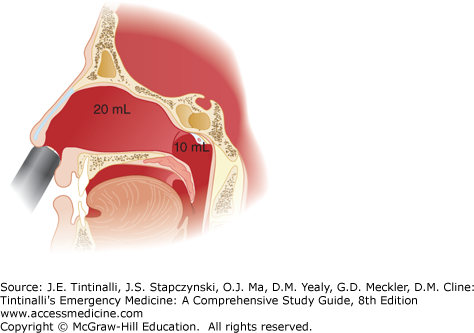

Failure to control hemorrhage after direct pressure, optimal use of vasoconstrictors, cautery, and anterior packing suggests (but is not diagnostic of) posterior bleeding. Bilateral anterior packing may help augment tamponade of the nasal septum. If that is not successful, the previously mentioned devices are usually available in longer lengths to provide posterior packing. If longer posterior-length packs do not work, ear, nose, and throat (ENT) consultation and assistance are needed. Posterior packing is associated with higher complication rates, including pressure necrosis, infection, hypoxia, and cardiac dysrhythmias, especially in patients with underlying cardiopulmonary disease, and thus, posterior packing is generally applied as a temporizing measure while awaiting ENT support. A formal nasal block may be required for analgesia, as posterior packing is often quite uncomfortable for the patient, but topical anesthesia may be sufficient if applied properly. The Rapid Rhino® has both an anterior (5.5 cm) and posterior (7.5 cm) balloon that can be inflated as required to tamponade bleeding. Figure 244-5 shows the placement of a dual balloon catheter. All posterior packing should be accompanied by an anterior pack.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree