INTRODUCTION

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are among the most widely used class of drugs in the United States, and all share inhibition of the cyclooxygenase enzyme as a mechanism of action. NSAIDs are effective antipyretics, analgesics, and anti-inflammatory agents. Because of their large therapeutic window, acute ingestion with overdoses rarely produces serious complications.1,2 The morbidity from NSAIDs in acute overdose is far overshadowed by complications of NSAIDs at therapeutic doses, which include GI bleeding, drug-induced renal failure, and atherosclerotic heart disease.3,4,5,6 Due to their increased risk for cardiovascular disease, rofecoxib and valdecoxib were withdrawn from the U.S. market in 2004 and 2005, respectively.

PHARMACOLOGY

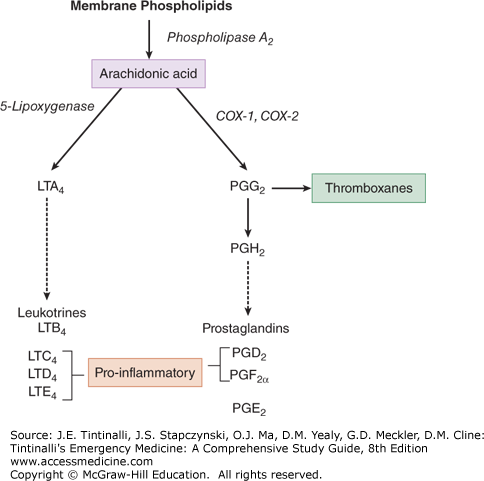

NSAIDs are structurally varied compounds with common therapeutic effects (Table 191-1). NSAIDs reversibly inhibit the enzyme cyclooxygenase, which is responsible for the production of prostaglandins from arachidonic acid (Figure 191-1). The anti-inflammatory effect of NSAIDs is through the inhibition of prostaglandin production, and they may also inhibit neutrophil migration via unclear mechanisms. NSAIDs are antipyretics through inhibition of prostaglandin E2 in the hypothalamus. NSAIDs attenuate prostaglandin-mediated hyperalgesia and local pain fiber stimulus.

| Class and Agent | Half-Life with Therapeutic Doses of Standard Oral Tablets or Capsules* (h) |

|---|---|

| Nonselective NSAIDs | |

| Salicylates | |

| Aspirin | 6 (salicylic acid) |

| Diflunisal | 8–12 |

| Salsalate | 16 |

| Acetic acids | |

| Diclofenac | 2 |

| Indomethacin | 4–5 |

| Ketorolac | 5 |

| Meclofenamate | 1–2 (15†) |

| Mefenamic acid | 2 |

| Nabumetone | <1 (22–26†) |

| Sulindac | 8 (16†) |

| Tolmetin | 5 |

| Propionic acids | |

| Fenoprofen | 3 |

| Flurbiprofen | 6–8 |

| Ibuprofen | 2 |

| Ketoprofen | 2–4 |

| Naproxen | 12–17 |

| Oxaprozin | 16–45 (38–57‡) |

| Pyrazolones | |

| Phenylbutazone | 72 |

| Oxicams | |

| Piroxicam | 50 |

| Partially selective COX-2 inhibitors | |

| Etodolac | 6–8 |

| Meloxicam | 20–24 |

| Selective COX-2 inhibitors | |

| Celecoxib | 11 |

| Rofecoxib | 17 |

| Valdecoxib | 8–11 |

FIGURE 191-1.

The arachidonic acid cascade is the primary pathway for the formation of arachidonic acid within cells from which inflammatory mediators—prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and thromboxanes—are generated. NSAIDs target this cellular mechanism to produce their anti-inflammatory effect. COX = cyclooxygenase; LT = leukotriene; PG = prostaglandin.

Two isoforms of cyclooxygenase (abbreviated COX-1 and COX-2) vary in presence and distribution.7 COX-1 is present with steady level of activity and is found primarily in blood vessels, kidneys, and stomach. In contrast, COX-2 is not normally found to a significant degree in human tissue with the possible exception of the brain and kidneys, unless its production is induced by local inflammation.

Cyclooxygenase inhibitors can be categorized as nonselective, partially selective, or selective regarding their inhibition of COX enzyme isoforms (Table 191-1). Most NSAIDs nonselectively inhibit both COX-1 and COX-2. COX-1 inhibition is responsible for most of the unwanted GI side effects of NSAIDs. Drugs, such as etodolac and meloxicam, were created to inhibit preferentially COX-2, theoretically reducing the unwanted GI effects. Unfortunately, the COX-2–selective compounds do not appear to be more effective mediators of inflammation or analgesia and are still associated with GI side effects in addition to usually being more expensive.8,9

All NSAIDs are rapidly absorbed from the GI tract, and most achieve peak serum levels within approximately 2 hours. They are highly protein bound in the plasma, have low volumes of distribution (approximately 0.2 L/kg), and cross the blood–brain barrier. NSAIDs undergo metabolism mainly in the liver via glucuronic acid conjugation or via liver enzymes before elimination in the urine or feces. Plasma half-lives of NSAIDs range from 2 hours for ibuprofen to greater than 50 hours for the long-acting agents piroxicam and phenylbutazone (Table 191-1). Creation of active metabolites may prolong the therapeutic effect beyond that of the parent compound.

Ingestion of large amounts of some drugs, such as ibuprofen and naproxen, exhibits slower absorption, taking 3 to 4 hours to achieve peak plasma levels. As greater amounts of NSAIDS are absorbed in large overdoses, greater fractions of free drug become available for toxicity in a nonlinear manner because protein binding is limited.

Topical NSAIDS are well absorbed through the skin and reach therapeutic levels in synovial fluid. They provide good pain relief for osteoarthritis, with very low blood levels and no toxic effects described to date.10,11

Daily aspirin therapy reduces the incidence of recurrent myocardial infarction and stroke via impairment of platelet aggregation. Ibuprofen administered three times per day competitively inhibits this aspirin effect on platelets via its interaction with the thromboxane pathway, undermining its cardioprotective effect. This observation may extend to other NSAIDs but not to diclofenac or the COX-2 inhibitors.12

NSAIDs can decrease the effectiveness of some antihypertensives including angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, diuretics, and α- and β-adrenergic antagonists. Inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis is believed to be a central mechanism for these effects. Lower prostaglandin levels result in alterations in the renin-angiotensin system causing decreased renal sodium clearance, water retention, and changes in vascular tone.13

Warfarin and NSAIDs have several important interactions that may increase the risk of bleeding.14 Some NSAIDs may displace warfarin from plasma proteins, but the effect is small and does not lead to increased anticoagulation. The selective COX-2 inhibitors at therapeutic doses also elevate prothrombin times, likely through decreased elimination of warfarin. Other nonselective NSAIDs have not been reported to change warfarin protein binding or elimination, but their use is not recommended in warfarin users because they inhibit platelet aggregation and can significantly increase the risk of bleeding.

NSAIDs may also decrease renal clearance via inhibition of renal prostaglandin synthesis, decreasing their vasodilatory effect, causing a decrease in renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate, and ultimately decreasing the rate of elimination of certain drugs. Therefore, NSAID use can lead to increased concentrations of consequential drugs such as lithium, methotrexate, and metformin. NSAIDs are a potential risk factor in the development of metformin-associated lactic acidosis, a rare complication of metformin therapy with a high mortality.15

CLINICAL FEATURES

NSAIDs are generally safe drugs but have a number of well-reported side effects at therapeutic doses (Table 191-2). It is generally believed that indomethacin and other long-acting agents, such as piroxicam, are responsible for a greater proportion of side effects, whereas the propionic acid agents, such as ibuprofen, are responsible for fewer side effects.

| Organ System | Clinical Toxicity |

|---|---|

| CNS | Behavioral changes, cognitive difficulties, headache, psychosis, aseptic meningitis |

| Cardiovascular | Increased risk of myocardial infarction and risk of sudden death following myocardial infarction |

| Pulmonary | Bronchospasm, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, pulmonary edema |

| GI | Dyspepsia,* nausea,* heartburn,* gastritis, gastric and duodenal erosions, mucosal bleeding,* gastric and duodenal perforation |

| Hepatic | Spectrum of hepatic injury ranging from asymptomatic elevation of serum transaminases to fulminant hepatic failure |

| Renal | Sodium and water retention,* hyperkalemia, azotemia,* acute tubular necrosis, interstitial nephritis, renal failure |

| Hematologic | Increased risk of bleeding, bone marrow suppression, aplastic anemia, agranulocytosis, red cell aplasia, hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia |

| Dermatologic | Maculopapular rashes, photosensitivity reactions, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis |

| Bone | Delayed wound and fracture healing |

| Reproductive | Slowed uterine contractions, premature closure of ductus arteriosus, fetal intracranial hemorrhage, necrotizing enterocolitis, oligohydramnios |

CNS adverse effects at therapeutic doses include headache, cognitive difficulties, behavioral change, and aseptic meningitis.16,17 Acute psychosis has been reported with indomethacin and sulindac use, which is hypothesized to result from the structural similarity of these NSAIDs to serotonin.

Patients with NSAID-induced aseptic meningitis may experience symptoms of headache, fever, and neck stiffness occurring within hours of a therapeutic dose.16,17

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree