NEUROTRAUMA

JULIE K. MCMANEMY, MD, MPH AND ANDREW JEA, MD

GOALS OF EMERGENCY THERAPY

Head injury is a common presentation in the pediatric emergency department. The challenge is to distinguish minor head trauma from clinically important traumatic brain injury (ciTBI). Identifying which children necessitate radiographic imaging and immediate recognition of ciTBI should be the goal of the evaluation. Management of the head-injured child should focus on stabilization, recognition of clinical deterioration, and early consultation of a neurosurgeon to decrease morbidity and mortality.

KEY POINTS

Headache is a common presenting symptom

Headache is a common presenting symptom

Most injuries are minor head trauma that do not necessitate clinical interventions

Most injuries are minor head trauma that do not necessitate clinical interventions

Infants with intracranial injuries may appear to be asymptomatic due to limitations in their neurologic examination

Infants with intracranial injuries may appear to be asymptomatic due to limitations in their neurologic examination

The most common cause of mortality from child abuse is head trauma

The most common cause of mortality from child abuse is head trauma

Cervical spine injury in children is rare but occur with TBI 20% of the time

Cervical spine injury in children is rare but occur with TBI 20% of the time

RELATED CHAPTERS

Resuscitation and Stabilization

• A General Approach to Ill and Injured Children: Chapter 1

• Approach to the Injured Child: Chapter 2

Signs and Symptoms

Clinical Pathways

Medical, Surgical and Trauma Emergencies

• Child Abuse/Assault: Chapter 95

• Spinal Cord Injury covered in this chapter

NEUROTRAUMA

Blunt Head Injury

CLINICAL PEARLS AND PITFALLS

• Infants with intracranial injuries may have limited neurologic examinations and appear asymptomatic

• Clinical assessment of infants may be challenging

• Index of suspicion for nonaccidental trauma should be low

Goal of Treatment

The primary goal in the evaluation of any patient who has sustained a blunt head injury is to determine the severity of the injury and identify ciTBI. As with all trauma evaluations, the initial goal of treatment is immediate stabilization.

Current Evidence. Neurotrauma is one of the most common reasons for emergency department evaluation with over 600,000 annual visits by children from birth to 19 years. Visits for younger children up to 4 years of age have increased significantly in the past several years, accounting for the highest rates of emergency department utilization. The age group with the highest number of fatalities continues to be adolescents ages 15 to 19. Common mechanisms of injury include falls, motor vehicle collisions either as a passenger or pedestrian struck by, bicycle accidents, sports-related, assaults and nonaccidental trauma. A detailed description of anatomy, pathophysiology, and causes of increased intracranial pressure (ICP) is included in Chapter 36 Injury: Head.

Briefly, the spectrum of traumatic brain injury (TBI) patterns ranges from minor head injury, concussion, skull fracture, pneumocephalus, intracranial hematoma, cerebral edema, diffuse axonal injury (DAI), cerebral herniation to death. Cerebral hematomas may be extra-axial, occurring in the epidural or subdural space or intra-axial, occurring within the parenchyma of the brain. Most recent studies have delineated other types of intracranial injury from ciTBI. The definition of ciTBI includes the presence of a depressed skull fracture necessitating surgical elevation, neurosurgical intervention including, but not limited to, invasive ICP monitoring, ventriculostomy, hematoma evacuation and/or decompressive craniectomy, endotracheal intubation for more than 24 hours, hospital admission for 48 hours or more, and death. Utilizing this definition, the overall incidence of ciTBI ranges from 0.02% to 4.4%.

TBI is the leading cause of acquired disability in children. Neurologic and cognitive deficits are related to patient age at time of injury, severity of injury, and degree of structural injury. Unique considerations should be given to children with shunt-dependent hydrocephalus and bleeding diatheses, platelet disorders, or coagulation disorders such as hemophilia.

Clinical Considerations (See Also Chapter 89 Head Trauma)

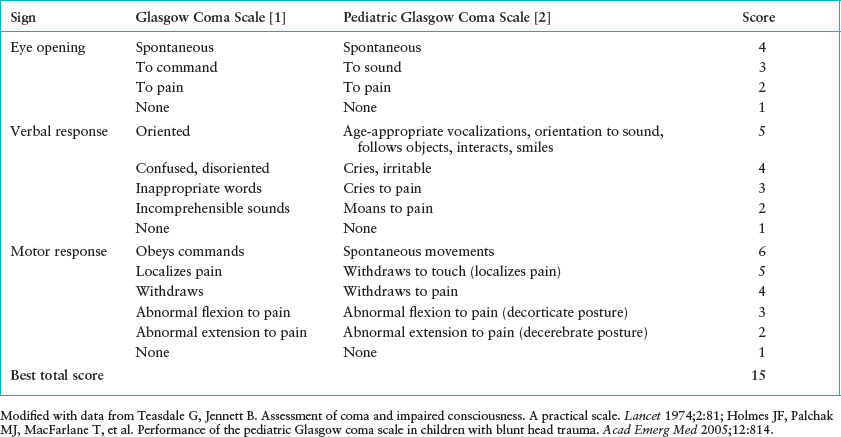

Clinical Recognition. The historical and physical features of TBI encompass a wide spectrum of signs and symptoms. For a detailed review of signs and symptoms, please review Chapter 36 Injury: Head. The presentation of infants may be nonspecific and include poor feeding, vomiting, irritability, a bulging anterior fontanelle, altered mental status defined as a pediatric Glasgow Coma Score of less than or equal to 14 (Table 121.1), lethargy, seizure, and presence of scalp hematoma and/or depression. Typical complaints in children include headache, progression of headache with increasing severity, vomiting, confusion, altered mental status defined as a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) of less than or equal to 14 (Table 121.1), seizure, lethargy, focal neurologic abnormality, obtundation, or signs of a basilar skull fracture, such as Battle sign, periorbital ecchymosis hemotympanum, and cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) otorrhea or rhinorrhea. Signs of impending cerebral herniation include altered mental status, pupillary changes, bradycardia, hypertension, and respiratory depression. Recent clinical decision rules to assist in the determination for emergent radiography have stratified ciTBI risk based on key historical and physical examination features. The clinical decision rules are applied to two separate patient populations, children less than 2 years of age and children 2 years of age and greater. Children less than 2 years of age provide a unique challenge to the clinician as they commonly present after minor trauma but may be asymptomatic or clinical assessment may be difficult. Additionally, the clinician must always have a low index of suspicion for nonaccidental trauma, as the incidence of child abuse in this age group is high. Head injury accounts for the highest mortality in nonaccidental or intentional injury. For a detailed review of inflicted injuries please refer to the Chapter 95 Child Abuse/Assault.

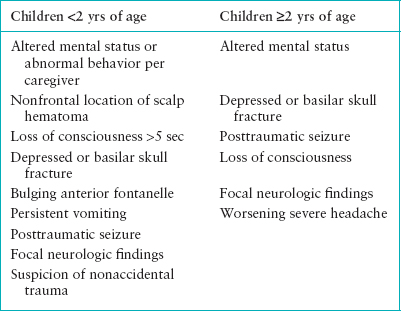

The features that place children less than 2 years of age at higher risk of having ciTBI include altered mental status, especially if the parent is concerned that the child is acting abnormally, parietal, temporal or occipital scalp hematoma, loss of consciousness >5 seconds, evidence of depressed or basilar skull fracture, bulging anterior fontanelle, persistent vomiting, posttraumatic seizure, focal neurologic examination findings, or suspicion of nonaccidental trauma. The features that place children 2 years of age and greater at higher risk of ciTBI include altered mental status, evidence of depressed or basilar skull fracture, posttraumatic seizure, prolonged loss of consciousness, worsening severe headache, and focal neurologic examination findings (see Table 121.2). Emergent neuroimaging should be performed for any child with one or more of these features. As certain features dictate the use of radiographic imaging, the absence of these features should compel the clinician to spare the patient unnecessary radiation exposure. Children less than the age 2 who have a normal mental status with normal behavior, lack a scalp hematoma or have a frontal scalp hematoma, without evidence of skull fracture and a normal neurologic examination should neither undergo radiographic imaging; nor should older children who have a normal mental status, no loss of consciousness, no vomiting, no severe headache, without evidence of a skull fracture and a normal neurologic examination.

The diagnostically challenging patient population is the children in the intermediate risk category. These are the children who may have isolated features indicative of ciTBI with resolution or improvement of symptoms and a normal neurologic examination. Observation for 4 to 6 hours after the injury may offer an alternative to emergent neuroimaging.

Diagnostic Imaging. Plain skull radiography has a limited role in evaluating blunt head injury as it cannot provide detail regarding intracranial injury. Because computed tomography (CT) is noninvasive and widely available, it is used for screening and diagnosis of intracranial injuries. Current generation 16-detector scanners are capable of rendering very high resolution images along with high speed data acquisition. CT imaging can detect mass lesions that may be surgical, early signs of cerebral edema including compression of the ventricular system and/or perimesencephalic cisterns, midline shift, or loss of grey to white matter interface. CT is preferred for detection of fractures and subarachnoid hemorrhage.

TABLE 121.1

GLASGOW COMA SCALE AND PEDIATRIC GLASGOW COMA SCALE

TABLE 121.2

CLINICAL FEATURES ASSOCIATED WITH HIGHER RISK OF CiTBI

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is more sensitive than CT as it provides greater anatomical detail of the brain and ventricles, but it can be less readily available and requires longer periods of time to obtain imaging. As an alternative, “fast” MRI techniques are being used to assess TBI. This option is not the current standard protocol in many facilities. MRI utilizing T1, T2, and fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images is more sensitive allowing delineation of the nature and timing of hemorrhage. Additionally, diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) outlines hypoxic-ischemic or DAI.

Management. As with any trauma evaluation, the initial assessment should focus on airway, breathing, circulation, disability and exposure per trauma guidelines. Please review the Chapters 2 Approach to the Injured Child and 89 Head Trauma for complete details as this is beyond the scope of this discussion. Management principles focus on airway management while maintaining cervical spine immobilization to provide adequate oxygenation and ventilation to prevent hypoxia and hypercarbia. Intravascular volume should be maintained to provide adequate cerebral perfusion pressure, thereby, preventing secondary brain injury. Certain adjuncts should be used in management of patients with suspected head injuries. Immobilization of the cervical spine should be maintained until it is determined that there is not a concomitant cervical spine injury (Spinal Cord Injury is covered in Chapter 120 Neck Trauma). This is accomplished with using the chin lift maneuver thus avoiding jaw thrust, application of semirigid cervical collar or inline manual stabilization. If intubation is determined to be necessary, endotracheal intubation is the preferred method. Evaluation by a neurosurgeon is preferred prior to intubation with neuromuscular blockade, but there should not be any delay in obtaining an advanced airway. Patients should be preoxygenated, and pretreatment medications that should be utilized are atropine, in all children less than 1 year of age, and lidocaine. Atropine at 0.02 mg per kg of weight with a maximum of 0.5 mg will help decrease the vagal response to intubation. Lidocaine at 1 to 2 mg per kg of weight with a maximum of 100 mg is used to prevent potential increased ICP by blunting airway reflexes. Rapid sequence intubation includes sedation and paralysis. Sedative medications should be used to decrease airway responses and keep the patient comfortable (refer to Chapter 3 Airway). Preferred medications for the child in whom a head injury is suspected include Etomidate and Midazolam. Neuromuscular blockade and paralysis may be achieved with Rocuronium or succinylcholine. There is no available outcome data regarding the use of sedatives and paralytic medications in children with ciTBI, and their use should be tailored to the individual patient.

Other noninvasive maneuvers should be a standard management to decrease ICP. The head of the bed should be elevated to 30 degrees, the head should be kept in a neutral position while maintaining cervical spine immobilization, ventilation to maintain PaCO2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree