12 Neonatal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation

• In newborn resuscitation, simultaneous auscultative assessment of the heart rate and respirations should precede more advanced interventions.

• Because visual determination has been found to be unreliable, pulse oximetry with the minimal oxygen supplementation necessary to maintain adequate oxygen saturation should be used to assess newborns.

• Endotracheal intubation should be considered for tracheal suctioning of meconium, heart rates below 100 beats/min that do not respond to initial bag-valve-mask ventilation, prolonged bag-valve-mask ventilation or chest compressions, administration of medications, and other special considerations such as congenital diaphragmatic hernia and extremely low birth weight.

• If the heart rate remains below 60 beats/min despite respiratory support, chest compressions should be performed at a rate of at least 100 compressions per minute via the two-finger or chest-encircling technique. The chest-encircling technique is preferred for chest compressions. The ratio of compressions to ventilations should be 3 : 1, with 90 compressions and 30 breaths to achieve approximately 120 events per minute to maximize ventilation at an achievable rate. Each event will be allotted approximately  second, with exhalation occurring during the first compression after each ventilation.

second, with exhalation occurring during the first compression after each ventilation.

Perspective

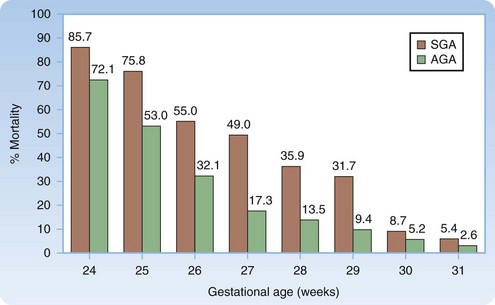

Approximately 10% of newborns require assistance after birth to achieve spontaneous breathing, and 1% need additional support. The likelihood of survival can be estimated from the gestational age and birth weight (Fig. 12.1).1

Survival with Comorbid Conditions

A 2001 study reviewing more than 700 neonatal intensive care unit admissions involving infants born at or before 25 weeks’ gestation found that survivors (63%) had a high incidence of chronic lung disease (51%), high-grade retinopathy of prematurity (32%), intraventricular hemorrhage (44%), nosocomial infection (38%), and necrotizing enterocolitis (11%).2

Anatomy

Anatomic considerations for the neonatal airway are similar to those discussed for pediatric patients (see Chapter 13), with the exception that the structures are even smaller and more anterior and superior, thus making visualization of the vocal cords an even greater challenge.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

“Yes” answers to the following three questions identify babies who do not require support after birth but can be dried, covered, and kept with the mother if desired.3

Interventions and Procedures: Resuscitation Steps

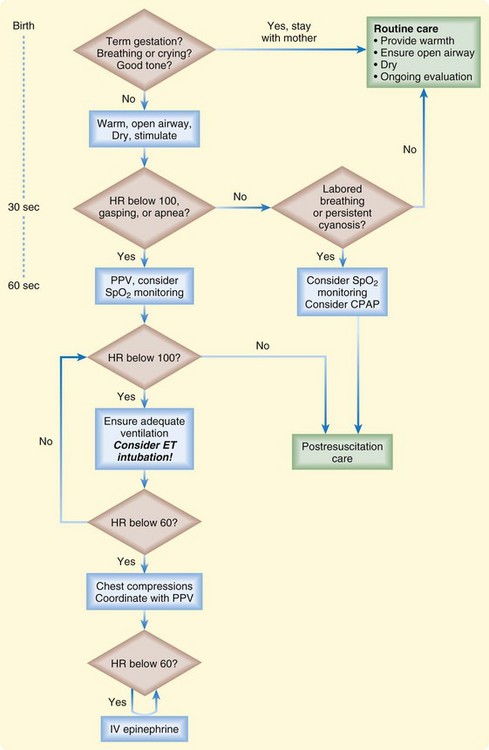

Figure 12.2 lists the steps in neonatal resuscitation.

Fig. 12.2 Newborn resuscitation algorithm.

(Modified from Kattwinkel J, Perlman JM, Aziz K, et al. Part 15: neonatal resuscitation: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation 2010;122:S909-19.)

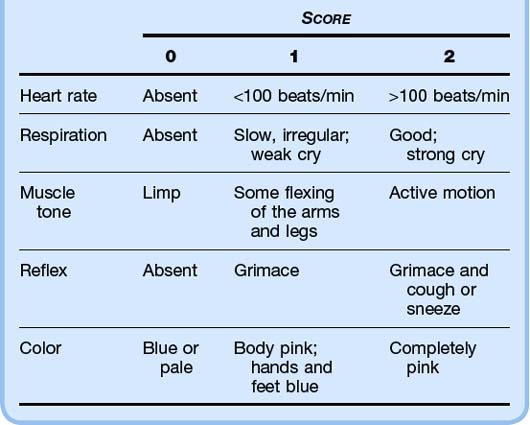

Apgar scores are measured at 1 minute and 5 minutes after delivery. These scores are used to (1) predict which infants will require resuscitation and (2) identify infants who are at higher risk for neonatal mortality. A score of 7 or higher is reassuring (Table 12.1).

Airway

The American Heart Association (AHA) no longer recommends routine intrapartum oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal suctioning because it has been shown to be associated with cardiopulmonary complications in healthy neonates. Oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal suctioning should be reserved for newborns with obvious upper airway obstruction and associated respiratory distress.3,4

Meconium-stained amniotic fluid occurs in up to 20% of deliveries, and as many as 9% of infants with meconium-stained amniotic fluid experience meconium aspiration syndrome (MAS), which carries a modern-day mortality rate of up to 40%.4

MAS occurs when the fetus aspirates meconium before or during birth, which leads to obstruction of the airways, atelectasis, severe hypoxia, inflammation, acidosis, and infection.5 The AHA guidelines regarding the management of a newborn with potential meconium aspiration make no distinction between thin and thick meconium because both have shown to lead to MAS.

In the absence of randomized controlled trials on routine tracheal suctioning of depressed infants born through meconium-stained amniotic fluid, the 2005 newborn resuscitation guidelines have not changed significantly. Thus, a nonvigorous newborn with meconium-stained amniotic fluid should not be suctioned on the mother’s perineum. Avoiding such suctioning prevents undue stimulation, which would lead to breathing and aspiration of meconium before endotracheal suctioning.6 Endotracheal intubation (ETI) and suctioning of meconium should be performed with a 10 French (F) to 14 F suction catheter and a meconium aspirator attached to an endotracheal tube. If intubation attempts are prolonged, bag-mask ventilation should not be delayed, especially when bradycardia is present.4

A vigorous neonate born with meconium-stained amniotic fluid does not require endotracheal suctioning for any level of meconium staining. Endotracheal suctioning has shown no benefit in this setting because the meconium has already caused irreversible damage to the lower airways. Vigorous is defined as having strong respiratory effort, good muscle tone, and a heart rate higher than 100 beats/min.7