INTRODUCTION AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

Neck masses are common in childhood, and although most are benign, malignancy is always a primary consideration. Correct diagnosis is challenging, but differentiating neck masses into inflammatory, congenital, or neoplastic categories is the first step toward diagnosis.

In patients referred to tertiary centers for surgical excision of a cervical lesion, 90% to 96% of lesions are benign and are predominantly congenital.1,2

GENERAL APPROACH

A thorough history and physical examination will narrow the broad differential for cervical lymphadenopathy. The acuity and laterality of node swelling are helpful for diagnosis. Typically, acute bilateral lymph nodes are due to a viral cause, acute unilateral nodes are due to a bacterial cause, and subacute/chronic nodes (>4 to 6 weeks) are due to granulomatous bacteria or noninfectious causes. This framework is most effective for diagnosis when combined with the general and specific features of different causes (Tables 122-1 and 122-2). Carefully record the features of all head and neck masses for future comparison. Lymph node location and characteristics give clues based on lymphatic drainage patterns. Look for systemic disease by assessing for generalized lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, testicular masses and/or enlargement in males, and the child’s overall condition.

| Historical Feature | Associated Etiology |

|---|---|

| Duration >4-6 weeks | Granulomatous lymphadenitis, congenital lesions, malignancies |

| Rate of growth | Fluctuating → inflammatory Progressive → malignancy |

| Pain | Infectious, or infected congenital lesion |

| Recent illness | Viral URTI → Reactive lymphadenopathy Pharyngitis → EBV, GAS |

| Neonatal period | Group B Streptococcus |

| Pain with meals | Sialoadenitis |

| Tuberculosis exposure (travel or sick contacts) | Tuberculosis mycobacteria |

| Undercooked meat or unpasteurized milk exposure | Toxoplasmosis |

| Cat exposure | Cat-scratch disease or toxoplasmosis |

| Animal exposure (including rabbits) | Tularemia, cat-scratch disease, toxoplasmosis |

| Mass since birth | Congenital |

| Birth trauma, forceps delivery | Fibromatosis colli |

| Constitutional symptoms (fever, weight loss, night sweats) | Tuberculosis mycobacteria, malignancy |

| Recent blood transfusions | EBV, CMV, HIV |

| Recent immunizations (DPT, polio, typhoid) | Reactive lymphadenopathy |

| Medications | Phenytoin, carbamazepine, isoniazid, hydralazine, and others |

| Physical Examination Finding | Associated Etiology |

|---|---|

| Laterality | Bilateral → viral Unilateral → bacterial |

| Size | >3 cm more likely congenital or malignant; fluctuations in size more likely infectious |

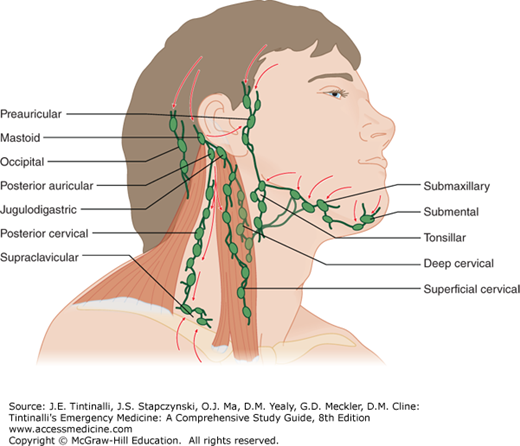

| Location | Depends on lymph drainage pattern (Figure 122-2) |

| Hard, rubbery, fixed, matted nodes | Possibly malignant |

| Signs of inflammation (tenderness, erythema, warmth) | Bacterial lymphadenitis or infected congenital lesion |

| Fluctuance | Abscess, often due to Staphylococcus aureus, or GAS |

| Difficulty swallowing or drooling | Deep space infection—retropharyngeal abscess |

| Viral URTI (cough, rhinorrhea, conjunctivitis) | Reactive lymphadenopathy |

| Pharyngitis | EBV mononucleosis, GAS |

| Periodontal disease | Anaerobic bacteria |

| Purulent salivary duct drainage | Sialoadenitis |

| Crossing jaw—suggests parotid involvement | Sialoadenitis, mumps, salivary gland malignancy |

| Violaceous skin change | Granulomatous lymphadenitis (TbM, NTM, CSD, tularemia) |

| Cold node | Granulomatous lymphadenitis or malignancy |

| Midline, moves with swallowing or tongue protrusion | Thyroglossal duct cyst |

| Transillumination | Lymphangioma (cystic hygroma) |

| Torticollis, laterally mobile, vertically immobile | Fibromatosis colli |

| Supraclavicular mass | Lymphoma, or less likely metastatic node |

| Midline mass | Thyroid cancer, thyroglossal duct cyst, dermoid cyst |

| Posterior mass | Rubella, toxoplasmosis, nasopharyngeal cancer |

| Hepatosplenomegaly | Malignancy, mononucleosis, systemic disease |

| Wasting or cachexia | Malignancy |

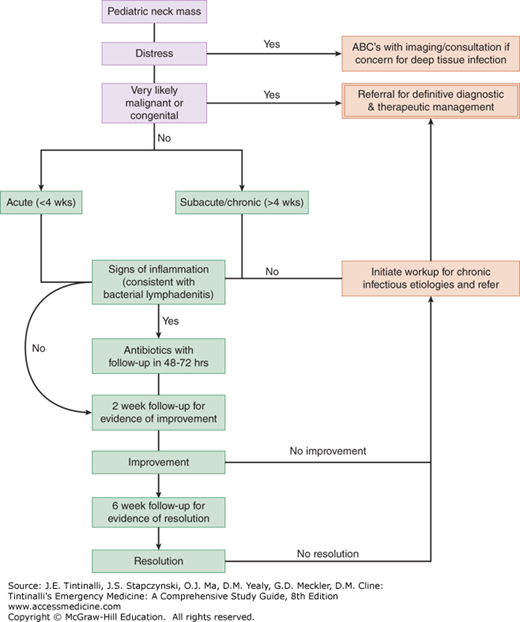

Ideally, the treatment of a childhood neck mass is directed at the specific cause; however, due to the many etiologies, this is not always obvious at first presentation. The majority of presentations are benign; however, the priority of childhood neck masses is to correctly identify those that are neoplastic. The algorithm in Figure 122-1 provides an approach to management based on suspected etiology and should be adapted to the individual patient. Follow-up of patients who are treated with antibiotics is necessary at 48 to 72 hours; if improvement of symptoms is not seen, then expanded coverage to include periodontal flora or MRSA is encouraged, and aspiration of fluctuant nodes for culture may be considered. Most lymphadenopathy will improve after 2 weeks of observation or antibiotics; however, all cases require 6-week follow-up to ensure resolution.

INFLAMMATORY NECK MASSES

The most common pediatric neck mass is an enlarged lymph node caused by infection. Be careful to consider masquerading lesions such as salivary gland infections, acutely infected congenital lesions, and, most importantly, malignancies.

Cervical lymph nodes drain the skin of the head and neck as well as the entire nasal, oral, and pharyngeal mucosa (Figure 122-2). Submandibular and cervical nodes are most common because they drain much of the oropharynx, including the adenoids and tonsils.3,4 Supraclavicular lymphadenopathy is suspicious for metastasis because it drains the abdomen and thorax.4

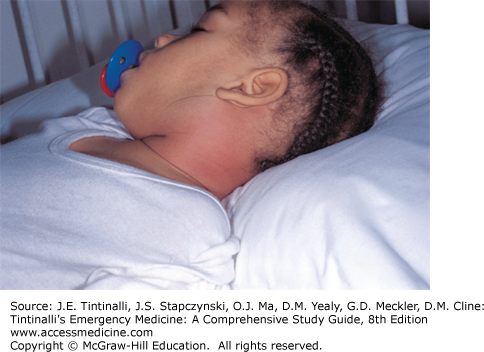

Palpable cervical lymph nodes are found in about 28% to 44% of healthy infants and children, with the incidence peaking in early childhood.3,5,6 Lymph nodes ≤1 cm in children <12 years old are considered normal.7,8 Most lymphadenopathy represents nonspecific reactive hyperplasia, often due to a viral upper respiratory tract infection.9 Lymphadenitis is lymph node inflammation (swelling, tenderness, warmth, erythema) and is most commonly due to viral or bacterial causes. Infection with a pyogenic organism may lead to liquefactive necrosis (suppuration) and abscess formation (Figure 122-3). If the immune system is unable to eradicate a particular organism, macrophages will attempt to contain it, forming a chronic granulomatous lymphadenitis.

Acute bilateral lymphadenopathy is usually due to viral infection and is self-limited. Common viruses include rhinovirus, parainfluenza, influenza, respiratory syncytial virus, coronavirus, reovirus, and adenovirus.10 Treatment is symptomatic and expectant.

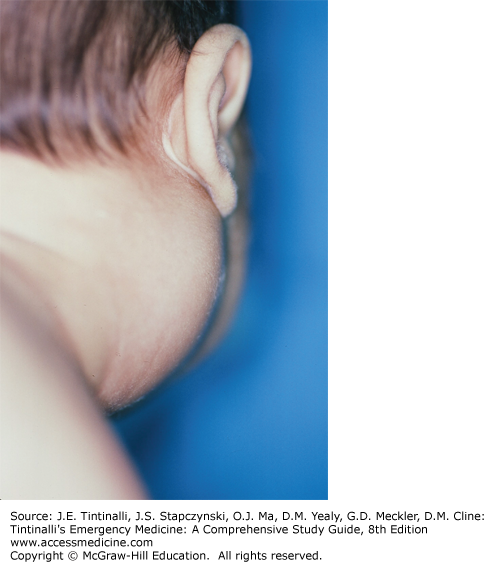

Alternative viral causes include infectious mononucleosis, characterized by fever, exudative pharyngitis, and significant lymphadenopathy (Figure 122-4). Heterophile antibodies or Epstein-Barr virus–specific immunoglobulin M confirms the diagnosis, and in immunocompetent patients, treatment is symptomatic. The classic viral exanthems associated with lymphadenopathy are measles (Koplik spots, conjunctivitis, and a descending rash) and rubella (associated with Forchheimer spots, rash, and polyarthritis). Acute bilateral lymphadenopathy and oral lesions may also be due to herpes simplex virus (gingivostomatitis) or coxsackie virus (herpangina). Pharyngitis caused by group A Streptococcus is accompanied by cervical lymphadenopathy.11 Bilateral swelling that extends over the jaw suggests parotid gland involvement due to mumps and may be associated with orchitis and a rash.

FIGURE 122-4.

Infectious mononucleosis typically presents with bilateral lymphadenopathy. A 6-year-old girl demonstrating bilateral lymphadenopathy. [Reproduced with permission from Shah BR, Lucchesi M: Atlas of Pediatric Emergency Medicine. © 2006, McGraw-Hill Education, New York, NY, Figure 11-14.]

Acute unilateral lymphadenopathy is most often due to bacterial lymphadenitis (Figure 122-5) caused by Staphylococcus aureus and group A Streptococcus.12 Lymph nodes will likely have signs of inflammation, and if an abscess has developed, fluctuance may be appreciated. Often the source of group A Streptococcus is the pharynx, whereas S. aureus originates from a break in the skin. Careful examination of the head, neck, throat, skin, and ears may identify a source that can be cultured.

Generally, lymph nodes <1 cm are normal and do not need treatment. If lymphadenitis measures between 1 and 3 cm, appropriate antibiotics treating group A Streptococcus and Staphylococcus for up to 2 weeks should lead to complete resolution.13 Nodes >3 cm raise suspicion for malignancy, but if the nodes are acute and inflammatory, a course of antibiotics and observation is reasonable.

Due to increasing β-lactamase–resistant Staphylococcus, first-line oral antibiotic choices are first-generation cephalosporins, cloxacillin/dicloxacillin/oxacillin, or clindamycin.12,14,15 If the child is unwell or immunocompromised, treat with IV cefazolin, nafcillin, or clindamycin. Reassess in 48 hours, and if no improvement is appreciated, consider changing antibiotics to treat methicillin-resistant S. aureus.16,17

Fluctuance of the node suggests abscess formation due to pyogenic bacteria, with the source often from the tonsils.15 Fluctuant nodes typically respond to antibiotics alone, but needle aspiration after local anesthesia may be helpful to avoid incision in cosmetically important areas.15 If a superficial abscess is pointing or not resolving within 2 weeks of antibiotics, then evaluation by US and incision and drainage may be necessary.18 When associated with torticollis or trismus, suspect a retropharyngeal abscess, and obtain imaging and/or surgical consultation (see chapter 123, “Stridor and Drooling in Infants and Children”).

Infants have a higher incidence of infection with group B Streptococcus rather than S. aureus or group A Streptococcus. Group B streptococcal infection can be associated with bacteremia, pneumonia, and meningitis.19,20

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree