INTRODUCTION AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

Mushrooms are a common toxic exposure, with >6600 poisonous mushroom exposures and six deaths reported to poison control centers in 2012 and more than half occurring in children <6 years of age.1

Fortunately, the majority of reported mushroom exposures have a benign outcome.2,3 To prevent mushroom poisoning, avoid eating wild mushrooms. There are no easily recognizable differences between nonpoisonous and poisonous mushrooms. Mushroom toxins are not heat labile and so are not destroyed or deactivated by cooking, canning, freezing, drying, or other means of food preparation.

Depending on the type of mushroom, adverse effects from ingestion range from mild GI symptoms to major cytotoxic effects resulting in organ failure and death. Toxicity varies based on the amount ingested, the age of the mushroom, the season, the geographic location, and the way in which the mushroom was prepared prior to ingestion. One person may show significant effects, whereas others may be asymptomatic after ingesting the same mushroom (Table 219-1).

| Symptoms | Mushrooms | Toxicity | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| GI symptoms | |||

| Onset <2 h | Chlorophyllum molybdites Omphalotus illudens Cantharellus cibarius Amanita caesarea | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea (occasionally bloody) | IV hydration Antiemetics |

| Onset 6–24 h | Gyromitra esculenta Amanita phalloides, Amanita bisporigera | Initial: nausea, vomiting, diarrhea Day 2: rise in AST, ALT levels Day 3: hepatic failure | IV hydration, glucose; monitor AST, ALT, bilirubin, BUN, and creatinine levels, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time For Amanita: activated charcoal Consider penicillin G, 300,000–1,000,000 units/kg/d Silymarin, 20–40 milligrams/kg/d Consider cimetidine, 4–10 grams/d Consider hyperbaric oxygen therapy |

Muscarinic syndrome Onset <30 min | Inocybe Clitocybe | SLUDGE syndrome (salivation, lacrimation, urination, defecation, GI hypermotility, and emesis) | Supportive; atropine, 0.01 milligram/kg, repeated as needed for severe secretions |

CNS excitement Onset <30 min | Amanita muscaria Amanita pantherina | Intoxication, dizziness, ataxia, visual disturbances, seizures, tachycardia, hypertension, warm dry skin, dry mouth, mydriasis (anticholinergic effects) | Supportive; sedation with diazepam, 0.1 milligram/kg IV for children; diazepam, 2–5 milligrams IV, or phenobarbital, 30 milligrams IV for adults |

Hallucinations Onset <30 min | Psilocybe Gymnopilus | Visual hallucinations, ataxia | Supportive; sedation with diazepam, 0.1 milligram/kg or 5 milligrams IV for adults, or phenobarbital, 0.5 milligram/kg or 30–60 milligrams IV for adults |

Disulfiram reaction 2–72 h after mushroom, and <30 min after alcohol | Coprinus | Headache, flushing, tachycardia, hyperventilation, shortness of breath, palpitations | Supportive; IV hydration β-Blockers for supraventricular tachycardia Norepinephrine for refractory hypotension |

Dermatitis 1–2 d after ingestion | Shiitake | Whip-like, linear, erythematous wheals, blanching erythematous patches, scattered petechiae, pruritus | Oral antihistamines, 0.1% triamcinolone ointment twice daily; spontaneously resolves within 1–3 wk |

Mushroom toxicity is divided into early toxicity (within 2 hours after ingestion) and delayed toxicity (6 hours to 20 days later).

Mushroom poisoning occurs in four main groups of individuals: young children who ingest poisonous mushrooms inadvertently, wild mushroom foragers, individuals attempting suicide or homicide, and individuals looking for a hallucinatory “high.” Identification of the mushroom ingested may be difficult and time consuming. Very often, foragers mix different species of mushrooms together, so it is not always clear that the species being identified is the same one that was ingested. Therefore, direct treatment by a patient’s symptoms rather than by attempts at mushroom identification. Treatment for mushroom poisoning is based on case reports and small series.3

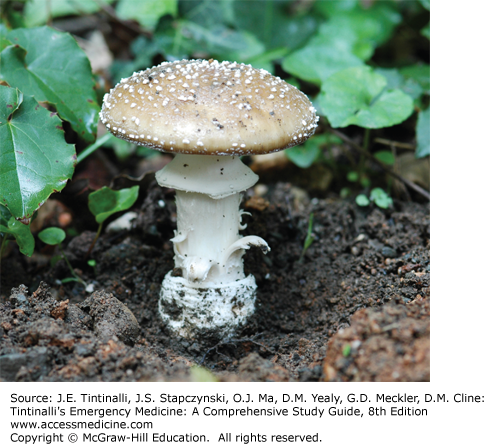

Nearly all fatalities in the United States and Europe occur from ingestion of mushrooms of the Amanita species (Amanita phalloides, Amanita virosa, and Amanita bisporigera).4 If Amanita ingestion is suspected, identification of the species may be helpful but is difficult because there are many Amanita mushrooms that are nontoxic. Amanita species generally have warts on the cap (remnants of the membrane covering the emerging mushroom), which give it a spotted appearance. The gills are “free,” ending before the stem begins. The stem characteristically has a membrane ring around it and widens as it enters the soil. In most cases, the stem of the mushroom is contained in a cup or volva, which may be underground (Figures 219-1, 219-2 and 219-3).

EARLY-ONSET GI SYMPTOMS

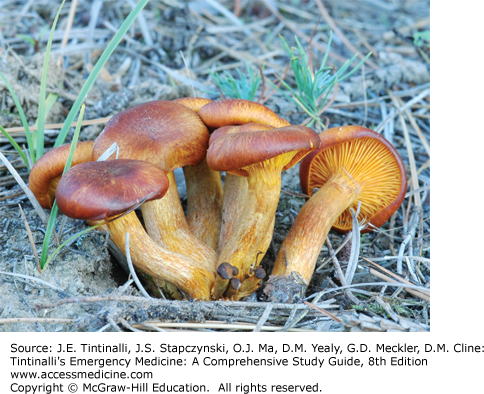

Most wild mushroom ingestions cause mild GI irritation, and mushrooms that cause GI irritation can be of many types. In North America and in almost every country, Chlorophyllum molybdites is particularly common and is sometimes mistaken for an Amanita.3 Many little brown mushrooms found commonly in lawns, and often accidentally ingested by children, are in this category. Omphalotus, Boletus, Entoloma, Gomphus, Hebeloma, Lactarius, and Verpa genera are other examples for this group (Figure 219-4). The actual toxin varies with the species of mushroom, but most toxins are poorly described.

The majority of mushroom-induced intoxications are mild and do not prompt a visit to the ED. C. molybdites, however, is an exception that may cause severe symptoms.5 Typically, patients present with acute onset of vomiting and diarrhea <2 hours after ingesting the mushroom. There may be intestinal cramping, chills, headaches, and myalgias. Diarrhea is usually watery, but occasionally bloody with fecal leukocytes. Most commonly, symptoms are mild and self-limited. Symptoms usually resolve within 24 hours but may last up to several days. Vomiting and diarrhea can cause dehydration and electrolyte imbalance. The presentation may be confused with acute gastroenteritis or acute food poisoning if the patient does not offer the history of mushroom ingestion.

Treat symptomatic toxic mushroom ingestion with activated charcoal 0.5 to 1.0 gram/kg, PO or by nasogastric tube. There is no role for prophylactic decontamination therapy of asymptomatic patients.6 Other treatment is largely supportive and includes IV fluid and electrolyte replacement when necessary. Antiemetics can be given, but do not give antidiarrheal agents, because they may prolong exposure to the toxin.2 In most cases, symptoms are self-limited, resolving within 12 to 24 hours. Some cases of Amanita smithiana ingestion present with early GI symptoms (between 30 minutes and 12 hours) and can progress to renal failure within 3 to 5 days.7

Once vomiting has subsided and the patient is tolerating oral fluids, discharge from the ED is safe. Rarely, symptoms may persist and hospitalization may be needed for fluid and electrolyte replacement. Recommend outpatient follow-up within 5 days, and provide return precautions (urinary changes, lumbar or flank pain).7

EARLY-ONSET NEUROLOGIC SYMPTOMS

Several classes of mushrooms can cause neurologic symptoms. These include the hallucinogenic mushrooms (“magic mushrooms”) that contain the chemical psilocybin, which is rapidly dephosphorylated by alkaline phosphatase to the more psychoactive chemical psilocin.8 Psilocin acts on serotonergic neurons in the CNS, causing effects similar to those of lysergic acid diethylamide. Mushrooms of the Psilocybe genus, which are the most commonly ingested in this class, are small brown or gold mushrooms that commonly grow on dung in warmer climates throughout the Pacific Northwest and southeastern United States as well as warm regions of Central America, South America, Asia, and Australia.9 They characteristically turn a greenish blue when bruised or cut. They may also be cultivated at home from purchased spores. Nontoxic mushrooms may also be laced with phencyclidine or lysergic acid diethylamide and sold as hallucinogenic mushrooms.

Mushrooms containing the isoxazole derivatives ibotenic acid and muscimol also possess neurologic effects, which are thought to be mediated by γ-aminobutyric acid and anticholinergic activity. Amanita muscaria is the principle representative of this group of mushrooms and is easily identified (Figure 219-1). It has an orange or red cap with white warts (remnants of the universal veil present in young specimens), as well as a ring (annulus) and cup (volva) on the stem. Amanita pantherina, another member of the group, is 5 to 14 cm in length and diameter, with a white to brown cap, and has the ring and cup on the stem (Figure 219-2). Both specimens grow under trees in woodlands throughout North America.

Symptoms typically develop within 2 hours of ingestion of hallucinogenic mushrooms. Euphoria, a heightened imagination, a loss of the sense of time, and visual distortions or hallucinations are common. Tachycardia and hypertension may be noted because of the presence of phenylethylamine in psilocybin-containing mushrooms.10 Fever and seizures have been reported in rare cases. Symptoms generally last 4 to 6 hours but can persist up to 12 hours.11 There are infrequent reports of flashbacks for up to 4 months after ingestion, particularly in association with other substances that alter cognition such as alcohol or marijuana.9

Patients ingesting isoxazole-containing mushrooms usually present with symptoms within 30 minutes of ingestion. Signs of muscarinic poisoning are the first apparent (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, vasodilation, diaphoresis, salivation). These are replaced by an atropine-like symptom complex about 30 minutes after ingestion (mydriasis, xerostomia, elevated temperature, increased blood pressure), along with drowsiness, amentia, dizziness, photosensitivity, euphoria, motor hyperactivity, ataxia, muscle jerking, hallucinations, and delirium with difficulty with perception of size, time, and place. Seizures have been reported in children. Symptoms are typically self-limited, resolving within 4 to 6 hours after ingestion. Headache and fatigue are reported to occur the day following ingestion, with headache lasting up to a few weeks.9

Treatment for ingestion of hallucinogenic mushrooms is largely supportive. Place the patient in a darkened, quiet room, devoid of visual stimuli, and provide reassurance. If sedation is required, benzodiazepines such as diazepam or lorazepam are preferred. Do not give anticholinergic agents because they may aggravate delirium.

Treat symptomatic ingestion of isoxazole-containing mushrooms with activated charcoal. Do not give syrup of ipecac because of the potential for CNS depression and seizures, which place the patient at risk for aspiration. In patients with severe vomiting and diarrhea, replace fluids and electrolytes. Appropriately restrain patients who are agitated, and provide sedation as necessary with benzodiazepines (diazepam or lorazepam). Treat seizures with benzodiazepines.

Consider treatment with physostigmine only for patients with severe anticholinergic symptoms. Physostigmine can produce bradycardia, hypotension, and seizures, so administration should be reserved for severely symptomatic patients. The dose is 1 to 2 milligrams IV in adults and 0.5 milligram IV in children, administered slowly. Monitor continuous cardiorespiratory effects and blood pressure during administration. Base the decision to discharge from the ED on duration of symptoms and need for ongoing pharmacologic sedation or intubation.

EARLY-ONSET MUSCARINIC SYMPTOMS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree