Chapter 40 Musculoskeletal Trauma

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, approximately 53% of all hospitalized injuries are because of fractures.1 Trauma to the bony skeleton produces pain, affects a person’s ability to do activities of daily living, and in some cases can be life threatening or limb threatening. The goals of caring for any trauma patient are to prioritize care to protect life, preserve function, and reduce long-term disability. All trauma patients should have a primary assessment to rule out problems with airway, breathing, circulation, and disability before attention is focused on injury-specific conditions. See Chapter 35, Assessment and Stabilization of the Trauma Patient, for a description of the primary assessment of the trauma patient. The purpose of this chapter is to provide an overview of initial and specific assessments and emergency care for musculoskeletal injuries.

Initial Assessment

Focused History

• The history helps the health care provider do a more thorough assessment by following a general rule as stated below. Always examine the joints above and below the obvious injury.

• Ask the patient to identify areas of pain, altered nerve function, and loss of extremity motor function.

• Mechanism of injury is used to direct primary and secondary assessments. It is important to distinguish low-energy forces (e.g., falls from level heights) from high-energy forces (e.g., motor vehicle crashes, falls from distance, high-velocity gunshots). In the latter, the force from the point of impact can be transmitted to distal structures and produce patterns of multiple injuries.

Inspection

Inspect the injured extremity for general appearance, deformity, and motion.

• Skin signs suggestive of a musculoskeletal injury include ecchymosis, pallor, dusky color, edema, and any open soft tissue wounds.

• Always examine the joints above and below the obvious injury.

• Note obvious deformities such as changes in size, shape, or alignment. It is helpful to compare an injured extremity with the uninjured one. Observe hand position in patients with hand injuries and decreased level of consciousness. Turn hand with palm up and note if all fingers are flexed in a gentle cascade. If any one finger remains extended, suspect tendon injury.2

• Loss of range of motion and subtle signs and symptoms suggestive of an extremity injury include the person favoring or hesitating to move the extremity (e.g., limping, holding the injured part).

Palpation

• Determine skin temperature, which is a rough estimate of arterial perfusion. Compare an injured extremity to the uninjured extremity.

• Put the extremity through active range of motion. Check motor strength distal to the injury, rating it on an objective scale and comparing it to the uninjured side. This allows for more consistent interrater assessments and identification of subtle changes.

• Palpate the limb or joint for tenderness and crepitus.

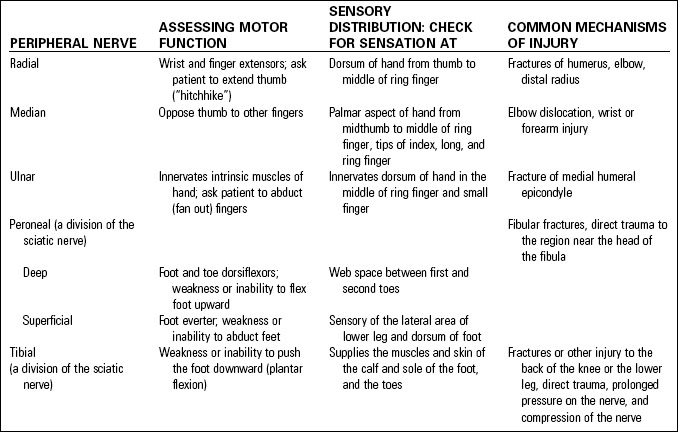

Assessing Neurovascular Status

• Assess function at the time of admission, after any manipulation, when the injured part is immobilized, and at intervals until after swelling has minimized.

• Check the patient’s ability to feel light touch in the injured extremity. It may be necessary to check for two-point discrimination. Assess response to pain if the patient has decreased level of consciousness.

• Assessment includes inspecting and palpating the involved structures. Significant findings are known as the Six P’s:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree