INTRODUCTION

Lesions of the mouth and throat are common in children and can range from benign conditions that require no intervention to significant systemic illness requiring extensive treatment and support (Table 121-1). Making the distinction between these conditions can be difficult. Mouth pain secondary to viral infections of the oropharynx is one of the most common presenting complaints of pediatric patients; however, most patients require no treatment beyond supportive care and pain control. Bacterial infections of the mouth and throat, such as pharyngitis and uvulitis, cause local and systemic illness and rarely can lead to life-threatening complications. The management of dental injuries, whether from neglect or trauma, differs for primary and permanent teeth.

| Anterior | Posterior | Diffuse |

|---|---|---|

| Aphthous ulcers | Adenovirus pharyngitis | Autoimmune disease |

| Contact stomatitis | Coxsackie virus | Candidiasis (thrush) |

| Herpes simplex gingivostomatitis | Cytomegalovirus Epstein-Barr virus | Chemotherapy-related mucositis |

| Trauma | Streptococcal pharyngitis | Medication-related (phenytoin [Dilantin]) |

| Vincent’s angina | ||

Stevens-Johnson syndrome Varicella-zoster |

NORMAL VARIANTS

Epstein pearls are remnants of embryonic development that present as white, slightly raised nodules seen most commonly midline at the junction of the soft and hard palates of neonates. They are often seen incidentally during feeding and do not cause the child any pain or discomfort. Most resolve spontaneously.

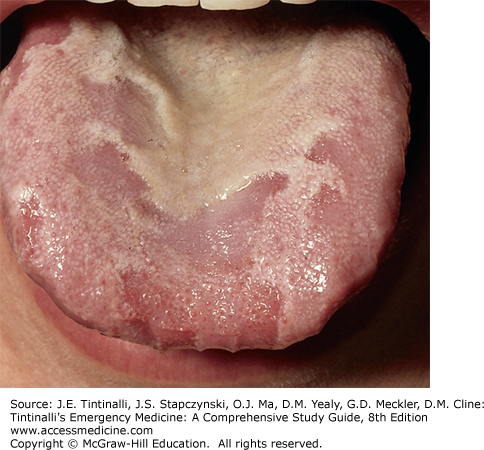

Geographic tongue or migratory glossitis (Figure 121-1) can be a source of great parental concern. It is a benign, asymptomatic condition and is often incidentally noticed by parents during another illness. Findings are an area of erythema and atrophy of the papillae of the tongue surrounded by a serpiginous, elevated white or yellow border usually located in the anterior two thirds. The lesions will improve and disappear gradually over time but tend to recur in other areas of the tongue. There is no known cause, although it has been associated with childhood allergies and atopy. No treatment other than reassurance is necessary.

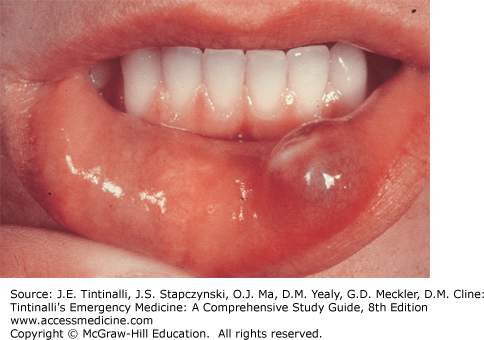

Mucoceles (Figure 121-2) and ranulas are lesions of the oral mucosa that present as small, bluish, discrete, mucosal swellings on the lower lip or sublingual areas.1 These are most often caused by minor trauma such as biting the lip.2 Intervention is needed only with disruption of feeding or development of speech. Adjacent salivary glands are usually removed in addition to the lesion to prevent recurrence.

Eruption cysts are smooth, painless bluish-black areas of swelling found over an erupting tooth that usually resolve with the eruption of the underlying tooth. Although these findings are frightening to the parent, they are benign in nature, often asymptomatic, and require no intervention.

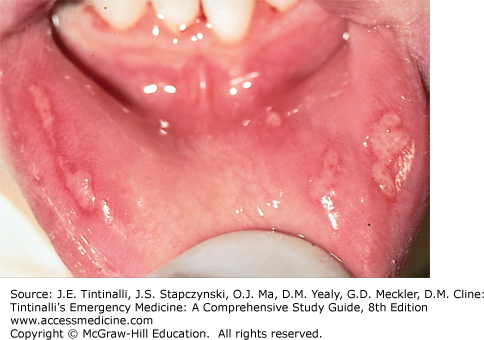

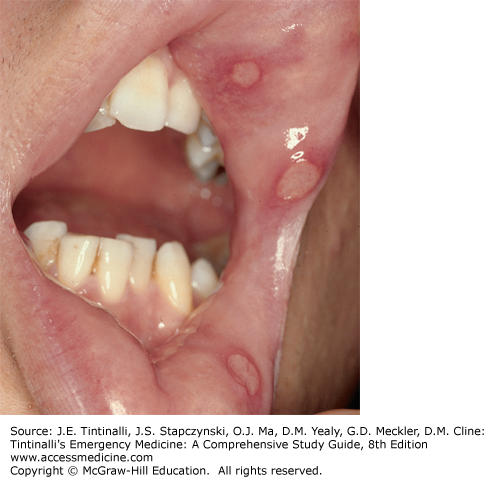

APHTHOUS ULCERS

Aphthous ulcers, also known as canker sores, are the most common form of recurrent oral ulcers, occurring in 5% to 25% of the general population.3 They present in children and adolescents as painful, shallow ulcers on the oral mucosa (Figures 121-3 and 121-4). The etiology of canker sores is unknown, but genetic factors, food allergies, local trauma, endocrine changes, stress, and anxiety are all thought to contribute to recurrence.4 They are found most frequently on the buccal and lingual mucosa. Spontaneous resolution after 7 to 10 days is the norm. Topical medications, such as antimicrobial mouthwashes and topical analgesics, can achieve the primary goal of reducing pain but do not hasten healing or improve recurrence or remission rates.

FIGURE 121-3.

Aphthous ulcers: Note the multiple ulcers of various sizes located on the lip and gingival mucosa. These lesions rarely occur on the immobile oral mucosa of the gingiva or hard palate. [Reproduced with permission from Knoop K, Stack L, Storrow A: Atlas of Emergency Medicine, 2nd ed. © 2002, McGraw-Hill, New York, Figure 6-33.]

FIGURE 121-4.

Aphthous ulcers: minor, multiple, very painful, gray-based ulcers with erythematous halos on the labial mucosa. [Reproduced with permission from Wolff KL, Johnson R, Suurmond R: Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas & Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology, 6th ed. © 2009, McGraw-Hill, New York, Figure 31-1.]

Less commonly, periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and cervical adenitis syndrome (PFAPA) can cause aphthous ulcers in children 2 to 6 years of age. Patients present with fever, malaise, exudative pharyngitis, cervical lymphadenopathy, and multiple oral ulcers lasting 4 to 6 days, often recurring multiple times a year. Recurrence is the key to diagnosis, as this constellation of symptoms is difficult to distinguish from viral infection, particularly in the ED where patient care is cross-sectional rather than longitudinal. The cause of PFAPA remains unknown, but most patients respond well to oral steroids, with resolution of symptoms within 24 hours. Some studies have also shown that tonsillectomy leads to complete resolution of symptoms and that vitamin D supplementation reduces number and duration of PFAPA episodes.5,6

STOMATITIS

The majority of infectious mouth and throat lesions are viral. Enteroviral infections commonly cause oral lesions with or without other physical findings such as fever, rash, abdominal pain, or diarrhea. Herpes viruses can cause oropharyngeal lesions that are extremely painful, may be recurrent, and are usually associated with high fever during primary infection. Adenovirus can cause acute pharyngitis in association with fever and tonsillar erythema. Exudative pharyngitis in association with fevers, fatigue, and malaise is frequent in infections with Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus.

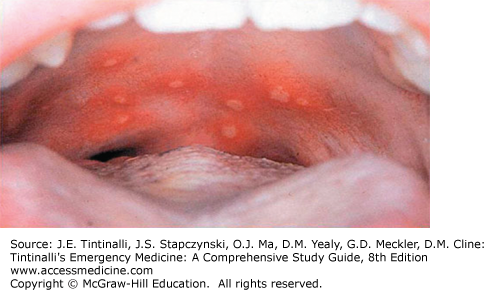

Herpangina is an enteroviral infection that causes a vesicular enanthem (Figure 121-5) of the tonsils and soft palate, affecting children 6 months to 10 years of age during late summer and early fall. It is primarily caused by Coxsackie virus A16 and human enterovirus 71, although other Coxsackie A and B genotypes are also common etiologic agents.7 These vesicles are often very painful and are accompanied by fever, difficulty swallowing, and dysphagia. Patients may complain of headache, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Diagnosis is primarily clinical. Viral culture is the gold standard for confirmation of infection; however, enteroviral polymerase chain reaction can detect enteroviral RNA from nasopharyngeal secretions, blood, urine, or feces much sooner and with higher sensitivity (87% to 100%; 95% from throat culture).8

Treatment is palliative because the symptoms are usually mild and lesions heal spontaneously after 3 to 5 days. Antipyretics and systemic analgesics aid with supportive care. Viscous lidocaine is generally not recommended for pain relief because it has no benefit over placebo in improving oral intake in affected children and also carries a risk of toxicity from lidocaine ingestion, with associated seizures.9,10 A mixture of diphenhydramine and Maalox applied orally in a swish-and-swallow fashion can provide local pain relief. When topical treatment does not suffice, systemic analgesics, including narcotics, may be necessary. Pay close attention to hydration status, because children can quickly become dehydrated, requiring admission for IV fluid replacement.

Hand, foot, and mouth disease is also seen with enteroviral infections.11 Coxsackie virus A16 is the most common cause, but A5, A9, A10, B2, B5, and enterovirus 71 subtypes have also been implicated.12,13 The disease is typically seen in children <5 years old but is most common in infants and toddlers. The infection has a seasonal distribution and primarily occurs in the spring and summer months.

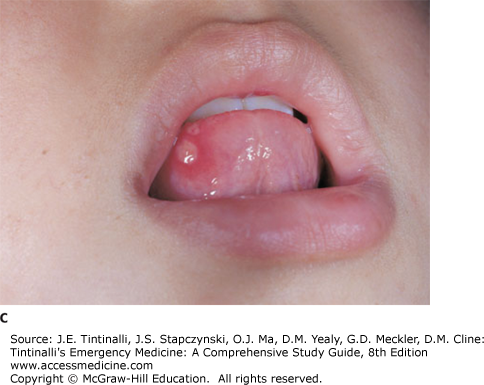

The illness generally follows a mild course, starting with a low-grade temperature lasting 2 to 3 days and associated with decreased appetite, malaise, vague abdominal pain, and mild upper respiratory symptoms. Children will then develop an enanthem of vesicles, followed by the exanthema, although both can occur simultaneously.

Oral lesions usually begin as erythematous macules and evolve into vesicles and ulcers over the course of 1 to 3 days, with new lesions appearing throughout the duration of illness. Lesions typically involve the palate, buccal mucosa, gingiva, and tongue. Pain from these ulcerations often leads to decreased oral intake and mild dehydration.

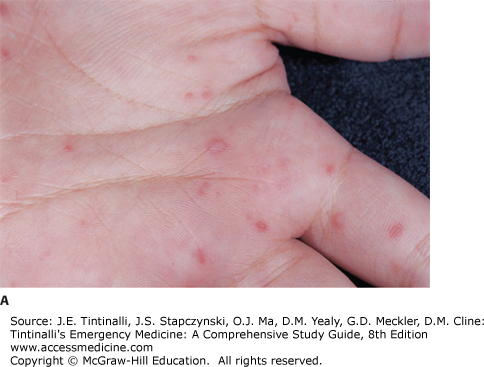

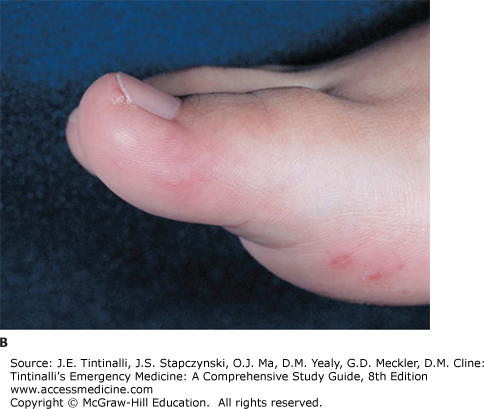

The associated rash appears on the palms of the hands, soles of the feet, and buttocks (Figure 121-6). Lesions begin as erythematous macules that later may develop into small nontender vesicles. The oral and skin lesions tend to resolve over 4 to 7 days.

Diagnosis is primarily clinical, although the virus can be isolated by viral culture or polymerase chain reaction from swabs of the vesicles and from stool specimens. Treatment involves supportive and symptomatic care with antipyretics, topical and oral analgesics, and oral rehydration. In rare cases, pain may lead to inadequate oral intake. Analgesics and IV fluids may be needed to treat dehydration. Rare complications of these infections include viral meningitis, meningoencephalitis, myocarditis, and sepsis.14,15 Diligent hand washing among children and caregivers is key to preventing spread.16

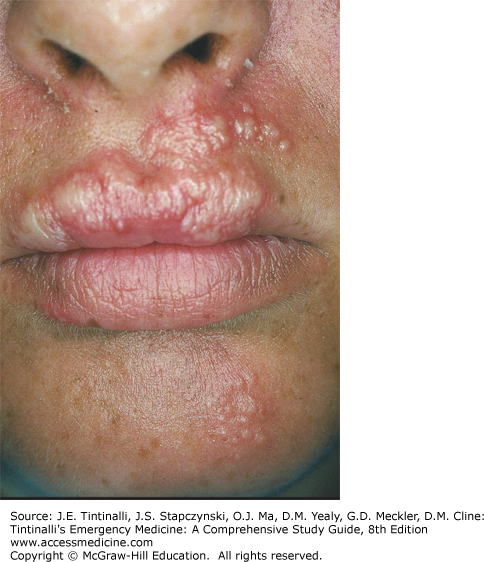

Herpes simplex virus can cause a variety of symptoms in the pediatric population. Infants and toddlers will often present with high fever, pharyngitis, and gingivostomatitis during their primary infection.17 Initial infection is often very difficult to distinguish from other viral etiologies. Most children go undiagnosed with herpes simplex virus until they later present with a more classic painful labial reactivation lesion.

Acute herpetic gingivostomatitis is the most common presentation of primary herpes infection in children18,19 (Figure 121-7). It usually presents at 6 months to 5 years of age, although primary herpes simplex virus infection may occur in older children and adults. Ninety percent of cases are due to herpes simplex virus type 1; however, herpes simplex virus type 2 has also been found to cause disease.20 Herpes transmission occurs via contact with infectious saliva, typically from caregivers who may be unaware of their infectious risk. The incubation period is 2 to 12 days, with a mean of 4 days.

Clinically, the disease presents with abrupt onset of high fever, irritability, decreased oral intake and drooling, and swollen, erythematous, friable gingiva. Physical findings include vesicular lesions in the oral cavity, ulcerations, and tender cervical lymphadenopathy. Symptoms may persist for up to 3 weeks, but more commonly last <1 week.21

Diagnosis is primarily clinical. Viral culture has been the gold standard of laboratory testing for years. However, the recovery of virus from lesions is low (7% to 25%). Herpes simplex virus polymerase chain reaction is a newer, more accurate assay with improved sensitivity in detecting infection from any lesions that are present.22 Tzanck smear of fluid from unroofed lesions 24 to 48 hours old showing multinucleated cells can also confirm the diagnosis but cannot differentiate infection between viruses within the herpesvirus family.

Treatment consists of supportive care with oral analgesics/antipyretics (acetaminophen or ibuprofen), topical analgesics, and systemic antiviral therapy for severe disease (acyclovir, 15 milligrams/kg PO divided five times a day for 7 days).23 Immunocompromised patients are at significantly higher risk for systemic dissemination, and hospitalization and treatment with IV acyclovir are recommended.

Prognosis of a primary herpes simplex virus infection beyond the fetal/neonatal period is usually very good. As the primary infection resolves, a lifelong latent residency of the virus within the trigeminal ganglion occurs, which may lead to less severe recurrences at the same site in the future.

PHARYNGITIS

It is important to distinguish between superficial and deep space infections of the mouth and throat. Deep space infections are discussed in chapter 123, “Stridor and Drooling in Infants and Children,” and are typically associated with toxic appearance, high fever, drooling, stridor, or changes in phonation, trismus, or torticollis. Simple pharyngitis, on the other hand, accounts for 1% to 2% of all visits to outpatient clinics and EDs, resulting in 7.3 million annual visits for children.24 Viral etiologies predominate in children with acute pharyngitis (Table 121-2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree