MINOR TRAUMA

MAGDY W. ATTIA, MD, FAAP, FACEP, YAMINI DURANI, MD, AND SARAH N. WEIHMILLER, MD, FAAP, FACEP

GOALS OF EMERGENCY CARE

Each year an estimated 12 million wounds are treated in emergency departments (EDs) in the United States. The first priority is stabilization of these patients who have sustained trauma who may have associated significant injuries. The care of minor injuries focuses on addressing pain, evaluating associated injuries, and wound closure. The key drivers in optimal wound repair are aimed at obtaining hemostasis, preventing infection, and achieving the best long-term cosmesis. This is performed in the context of a focus on patient and parental satisfaction, which is driven in the short term by timeliness of care and length of stay, and in the long term by avoidance of complications, including infection, hypertrophic scarring or keloid formation, and poor cosmetic results.

KEY POINTS

Children with minor trauma should be assessed for any associated serious injuries and wound management should not preempt care of more life-threatening injuries.

Children with minor trauma should be assessed for any associated serious injuries and wound management should not preempt care of more life-threatening injuries.

A thorough evaluation includes learning the mechanism of injury, the age of the wound, determining if there is a retained foreign body, and a careful physical examination that includes assessing for any other associated injuries.

A thorough evaluation includes learning the mechanism of injury, the age of the wound, determining if there is a retained foreign body, and a careful physical examination that includes assessing for any other associated injuries.

All wounds should be examined before and after cleansing to determine the best plan for repair.

All wounds should be examined before and after cleansing to determine the best plan for repair.

All wounds heal by scarring but the goal is to minimize its appearance.

All wounds heal by scarring but the goal is to minimize its appearance.

The use of absorbable sutures in pediatrics is favored in certain situations, as it avoids an additional procedure of suture removal in children.

The use of absorbable sutures in pediatrics is favored in certain situations, as it avoids an additional procedure of suture removal in children.

The use of topical anesthetics, anxiolysis, child life specialists, and distraction techniques can all be helpful and effective to facilitate wound repair.

The use of topical anesthetics, anxiolysis, child life specialists, and distraction techniques can all be helpful and effective to facilitate wound repair.

Patient and parent satisfaction as they apply to timeliness of care and avoidance of complications such as infection and poor cosmetic results are important factors to consider when making decisions about wound care.

Patient and parent satisfaction as they apply to timeliness of care and avoidance of complications such as infection and poor cosmetic results are important factors to consider when making decisions about wound care.

RELATED CHAPTERS

Resuscitation and Stabilization

• A General Approach to Ill and Injured Children: Chapter 1

• Approach to the Injured Child: Chapter 2

Medical, Surgical, and Trauma

• Infectious Disease Emergencies: Chapter 102

• Genitourinary Trauma: Chapter 116

• Musculoskeletal Emergencies: Chapter 129

Procedures and Appendices

• Procedural Sedation: Chapter 140

GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF MINOR WOUND REPAIR

The goals of wound repair are to obtain hemostasis, prevent infection, and achieve optimal cosmetic outcomes.

Obtaining Hemostasis

Hemostasis is important not only to prevent ongoing bleeding but also for clear wound visualization prior to any repair. Application of direct pressure with gauze is the fastest and most commonly used technique to obtain hemostasis. If there is continued bleeding, applying a blood pressure cuff or tourniquet proximal to the wound for a short period is acceptable. Injecting a local anesthetic with a vasoconstrictor such as epinephrine can help with hemostasis but should be used with caution in areas of end organ blood supply, such as digits.

Prevention of Infection

A primary goal of closure of open wounds is to prevent infection. Bacteria inhabit normal intact skin. This is the usual source of infection when skin tissue is disrupted. The amount of bacteria on the skin varies by anatomic location. High counts of bacteria are in moist areas such as the axilla and perineum, as well as in areas of exposed skin such as hand, face, and feet. Low counts of bacteria exist in dry areas such as the back, chest, and abdomen. Areas colonized with high bacterial contamination are most prone to infection. Wounds in regions of high vascularity, such as the scalp and face, more easily resist bacterial infection despite the high bacteria count. Certainly, the oral cavity is highly contaminated with bacteria, and this is an important source of infection when a child sustains a bite wound.

Wounds inflicted by shearing forces with a sharp object such as a knife cause minimal devitalization of adjacent areas and thus are less likely to lead to infection. Wounds caused by a blunt object striking the skin at an angle of less than 90 degrees result in a tension injury such as an avulsion or flap. These injuries involve a larger force applied to the skin than that of a shearing injury, and frequently there is more devitalized tissue. They are more likely to become infected than shearing injuries and are often more difficult to repair. Finally, compression injuries from blunt trauma perpendicular to the skin cause the most tissue disruption and devitalization. These wounds are characterized by ragged edges, and lead to the highest infection rates and risk of scarring.

Cosmesis and Wound Healing

The final aim of wound repair is to optimize cosmesis. Normal skin is under constant tension due to high collagen content. Tension is also produced in part by underlying structures such as joints and muscles. The amount of tension varies by anatomic location and position of a body part. Lacerations that run parallel to joints and normal skinfolds usually heal more quickly and with better cosmetic results. Wounds under a large amount of tension, crossing joints, or perpendicular to wrinkle lines may heal with wide, more visible scars.

Lacerations regain about 5% of their previous strength 2 weeks after injury, 30% after 1 to 2 months, and full tensile strength 6 to 8 months after the original injury. Many factors, such as infection, tissue edema, and poor nutrition, may delay this progression.

All wounds deeper than the dermis have the potential for scar formation. Scar formation involves the laying down of collagen, which is a complex process essential in restoring tensile strength of the skin. Collagen synthesis begins within 48 hours of the injury and reaches a peak within the first week afterward. Anything that interferes with collagen synthesis, such as infection, may lead to wound dehiscence at this time. Tissue contraction is expected with all healing wounds through the action of fibroblasts. Therefore, eversion of suture lines is desired at the time of repair so the skin will contract to a flat surface after healing. Remodeling may occur for up to 12 months. The scar may fade and recede over the first 3 months, and the final appearance of the scar may not be apparent until 6 to 9 months after injury.

Parental Satisfaction

In general, there are many factors that influence parental and patient satisfaction with their ED experience. In the case of lacerations, as in any pain-inducing condition, parents are concerned that their child’s pain, both at presentation and during any repair, is addressed properly. Additionally, parents are almost always concerned about the cosmetic outcome of the wound, particularly in the case of facial lacerations. Communicating information about the healing process, the nature of the wound, and the expected cosmetic outcome, as well as the timeline for complete healing can prevent dissatisfaction later on.

Rate of Wound Infection after Repair

The rate of wound infection is reported between 2% and 10%. Decreasing the likelihood of infection can help prevent additional morbidity, and optimize cosmesis as wounds that are infected during the healing process are more likely to scar. Efforts to reduce the risk of infection can be achieved by proper techniques discussed throughout the chapter.

Current Evidence

Lacerations account for 30% to 40% of all injuries for which care is sought in a pediatric ED. Blunt trauma with sufficient force or contact with sharp objects causes the majority of lacerations. Animal bites account for the remainder. More than 40% of the wounds involve a fall. Boys are injured twice as often as girls. The mechanism of injury varies with the patient’s age. In younger children, falls and accidents are classic mechanisms; violent encounters are more likely to be the cause in older children.

Two-thirds of the injuries occur during warm weather months, although half of the injuries in an urban environment occur indoors. Deaths from minor lacerations are rare; however, complications occur in nearly 10%. Children are less likely to get wound infections compared with adults. In children, the infection rate is about 2% for all sutured wounds. The risk of infection increases if there is a delay in primary closure.

Absorbable sutures for the repair of facial lacerations in children can be used to avoid the need for suture removal. Data support that these sutures have equally acceptable cosmetic outcomes in facial lacerations.

In pediatrics, it is important to consider painless alternatives to sutures in some cases. These include tape strips and tissue adhesives (or skin glue). Tape has the advantage of not leading to marks in the skin, minimal tissue reaction, and fewer wound infections than with sutures. Multiple studies have demonstrated that the cosmetic results of skin glue are comparable to those of sutures.

The benefits of the use of routine prophylactic oral antibiotics to prevent wound infection have not been proven and their use is controversial. The risk of antibiotic use from allergic reaction to growth of resistant organisms may outweigh their benefits. Antibiotics are given for wounds with high risk of infection such as bites and heavily contaminated wounds.

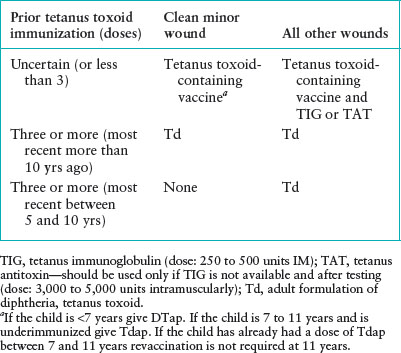

The immunization and tetanus status of a patient with a wound should always be obtained and protocol followed as per administration guidelines for tetanus prophylaxis, which is discussed later in the chapter (Table 118.1).

TABLE 118.1

TETANUS PROPHYLAXIS

Clinical Considerations

Triage Considerations

Children with minor trauma should be assessed for associated significant injuries. Injuries that compromise airway, breathing or circulation (systemically or locally, such as a limb) require immediate attention.

Wound management should not preempt care of more life-threatening injuries. If there are no significant injuries, the focus should move to addressing hemostasis and pain control. Application of topical anesthetics and administration of oral analgesics can be initiated at triage. Once these measures have been initiated, the emergency physician should aim for appropriate and timely wound repair.

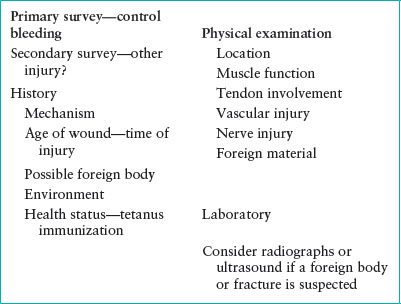

Clinical Assessment

History. In the evaluation of a laceration, it is important to learn the mechanism of the injury because this has a direct impact on management plans. For instance, if the wound was caused by an animal bite, the likelihood of infection and devitalized tissue is higher, thus wound closure may be avoided and healing by secondary intention may be preferred (Chapter 102 Infectious Disease Emergencies). Similarly, a wound caused by a blunt object may be associated with an underlying fracture or crush injury. These injuries are inherently more complicated and may require surgical consultation and hospital admission. A wound caused by a sharp or projectile object may cause deeper tissue or vascular injury. It is also important to determine the age of the wound, as well as the possibility of a foreign body in the wound, since these factors also determine the management of the wound repair.

The emergency physician should consider the location of the wound. If the wound is in the neck area, there may be possible extension through the platysma muscle, with potential for a serious injury to underlying structures. If the wound involves the chest, the clinician should look for crepitus in the subcutaneous tissue, suggesting injury to the underlying lung. An injury to the lower extremities is more likely to result in infection because of the relatively poor blood supply. Likewise, a wound overlying a joint space can be complicated if the joint cavity is violated. Injury to distal body parts such as the ears, nose, and fingers may threaten the viability of more distal tissues because of vascular compromise. Conversely, in areas where the vascular supply is robust, such as the face, scalp, and tongue, the infection rate is low regardless of the mechanism of injury.

Assess the environment in which the injury occurred. If the injury occurred on the street, it is possible that small particulate matter may be embedded in the wound. If this debris is left in place, tattooing of the skin could result, leaving an unfavorable appearance to the healed wound. Injuries that occurred in a field, farm, or a wet, swampy area may have high bacterial loads.

The patient’s health status and past medical history should be addressed to determine if there are additional risk factors for poor healing. If the patient has diabetes, immunosuppression, malnutrition, or other chronic conditions, such as cyanotic heart disease, chronic respiratory problems, or renal insufficiency, higher infection rates may be anticipated. Bleeding disorders and current medications should be determined because some drugs, such as ibuprofen and corticosteroids, may also have an impact on wound healing. A history of allergies to latex, antibiotics, and local anesthetics, as well as the child’s tetanus status should be determined.

Physical Examination. A careful physical examination is essential before giving local anesthesia. First, determine whether there is an associated injury distant from the obvious wound. It is important to assess the wound for vascular damage and to control bleeding if present. Brisk flow of blood may indicate injury to a major vessel. These vessels can usually be safely tamponaded and later ligated or sutured. The bleeding site must be identified, although it is often obscured by profuse bleeding. Pressure applied to the site or temporary use of a tourniquet or inflated blood pressure cuff (less than 2 hours) can help control hemorrhage and allow for identification of the bleeding vessel. Blind clamping of an artery should be avoided except in the scalp. Palpation of pulses and capillary refill distal to the site of injury must be checked.

Next, potential nerve damage must be assessed. For example, in a cooperative child, the physician should always test the median and ulnar nerve of an injured upper extremity. If a young child does not permit this, sensation may be tested with use of pinprick. Fortunately, when sensation is intact, motor function of the nerve is usually also intact.

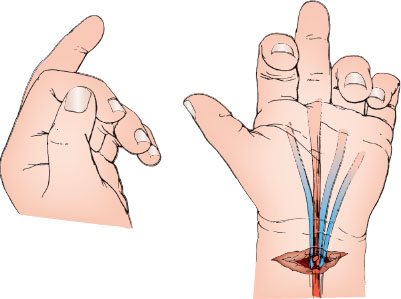

Next, the wound must be evaluated for possible tendon injury. The superficial location of extensor tendons of the dorsum of the hand predisposes them to injury. Tendon injuries are sometimes visible if the wound is wide and deep. For example, a torn tendon on the flexor surface of the forearm may be seen when the patient with a laceration to the wrist is asked to flex the hand and wrist. Unless the tendon injury is obvious, wounds over joints and tendons should be put through a full range of motion. A young patient may not be cooperative enough to flex and extend the fingers on command. Therefore, it is important to inspect the resting position of the injured hand in a young child to note a flexor tendon injury to the finger. One digit may be found extended at rest, while the other uninjured digits are flexed (Fig. 118.1). Applying a noxious stimulus and noting inability to withdraw the finger that is tested may show injury to the extensor tendons.

FIGURE 118.1 A seemingly superficial laceration at the wrist might be treated simply by closure of the subcutaneous tissue and skin, unless one appreciates the abnormal posture of a finger when the hand is at rest. The loss of normal flexor tone as a result of a divided superficial tendon results in the involved finger lying in a position of relative extension.

TABLE 118.2

WOUND ASSESSMENT—GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Role for Imaging. If the history or physical examination raises concern for possible foreign material in the wound, consider obtaining a radiograph or an ultrasound of the area. This is especially important in assessing a wound caused by glass. A deeply embedded piece of glass may be missed without radiographs or ultrasound. Some recommend obtaining plain radiographs in all cases in which glass is involved, except for the most superficial wounds. Ultrasound is more sensitive in detecting and localizing foreign bodies and can identify those that are nonradiopaque, such as plastic and wood, which will not be seen on plain films. It is a good idea to further inspect for foreign material after the wound is anesthetized.

Finally, bones nearby the wound should be palpated for crepitus, tenderness, or deformity, which may suggest a fracture. Obtain radiographs to confirm suspicious findings. Wounds overlying a fracture may constitute an open fracture and deserve consultation with an orthopedic surgeon for possible repair in the operating room. Table 118.2 summarizes general principles of wound assessment.

Patients found to have vascular, nerve, or tendon injury or deep, extensive wounds to the face merit consideration for consultation with a surgical specialist for possible repair in the operating room.

Management

Decision to Close the Wound. Most wounds may be closed primarily, meaning the wound edges are approximated as soon as possible after the injury to speed healing and improve the cosmetic result. If primary closure is delayed, the risk of subsequent infection increases. Some authors suggest that the “golden period” for wound closure is 6 hours. However, wounds at low risk for infection (e.g., a clean kitchen knife injury) can be closed even 12 to 24 hours after the injury.

Most wounds of the face are best closed primarily, even up to 24 hours after injury to achieve an optimal cosmetic effect. If the wound is extensive or has a high potential for infection (e.g., a dog bite on the face), thorough irrigation is essential, and in some cases, the operating room may be the best site for this repair. Conversely, wounds at high risk for infection such as those in anatomic locations with poor blood supply, contaminated or crush wounds, and those involving immunocompromised hosts should be closed promptly, within 6 hours of injury. Some contaminated wounds (e.g., animal or human bites or those occurring on a farm) in an immunocompromised host should not be sutured, even if the patient presents immediately for care. Some wounds should be allowed to heal by secondary intention (secondary closure), although scar formation may be more unsatisfactory. Infected wounds, ulcers, and many animal bites are best left to heal by granulation and reepithelialization. Human bites over the metacarpophalangeal joints (clenched-fist bites) are especially prone to infection and risk infection with primary closure. Puncture wounds to the foot, with only a small laceration and a low concern for cosmetic results, may also be left open. A small sterile wick of iodoform gauze may be placed inside the wound to keep the edges open. This gauze can be removed after 2 to 3 days, and the subsequent granulation tissue will aid healing.

If a wound is not closed initially, delayed primary closure (tertiary closure) can be considered after the risk of infection decreases, about 3 to 5 days later. This is recommended for selected heavily contaminated wounds and those associated with extensive damage. These uncommon wounds in pediatrics might include: high-velocity missile injuries, crush injuries, explosion injuries of the hand, industrial wounds, those occurring on a farm and perhaps bite wounds. The wound should be cleaned and debrided and covered at the time of initial presentation, then reassessed in a few days for infection. A contaminated but healing wound may gradually gain sufficient resistance to infection to permit uncomplicated closure at a later time. This approach may reduce discomfort and lead to a better cosmetic result than no repair. Tertiary closure is used rarely in pediatrics because children have few severely contaminated wounds.

Preparing the Child and Family. It is important to reassure the child and the family that everything will be done to care for the wound appropriately and to relieve the patient’s pain and anxiety. In many cases, early removal of blood and foreign material from the surface of the wound is reassuring. Also, carefully chosen words will reduce fear for the procedure. The physician must honestly warn the patient of an impending painful stimulus but may leave open the possibility that it may not hurt as much as the child thinks. Appearing unhurried and confident, giving the child some control of the situation, and explaining the upcoming procedure seems to help reduce anxiety and pain. The parent(s) and child should be informed that steps will be taken to make the procedure as quick and painless as possible, such as with the use of topical anesthetics. The clinician should provide an age-appropriate empathic explanation, to reduce anxiety. Prepare instruments that may be frightening, such as needles and scalpels, away from the child. Distraction techniques, such as allowing the child to listen to music or view age-appropriate, entertaining videos during the procedure can be quite effective (see Chapter 1 A General Approach to Ill and Injured Children). Child life specialists, if available, are also a good resource.

Inviting the parent to be in the room increases their level of confidence in the physician and can improve their overall satisfaction with the visit. Most parents want to be present during wound repair in the ED, and most can be a stabilizing force if properly oriented. The parent can reassure or distract the child with a story while maintaining physical contact under necessary drapes and restraints. It is usually best if the parent is sitting down and focusing on the child, rather than directly observing the procedure.

Appropriate use of sedation and local anesthetics is essential for successful repair of lacerations in some children. Some younger children can undergo repair after being placed in a restraining device, such as a papoose board, or wrapping the child securely but comfortably in a bedsheet for better immobilization. Restraint is needed to ensure the child’s safety and allow for more rapid completion of the procedure. Because the child may get excessively warm while being restrained, it is important to ensure proper ventilation and assess the child’s comfort during the restraint process. A caring, but firm nurse or assistant is often needed to further immobilize the injured body part and complete the procedure successfully. It is better to use such hospital personnel instead of parents to immobilize a child. A school-age child can usually cooperate without restraint. Some children may require procedural sedation and/or anesthesia depending on the type, extent and location of the wound, and the child’s age and level of development (see Chapter 140 Procedural Sedation). Some extensive wounds may warrant more significant repair that is best accomplished with surgical consultation and possible intraoperative repair.

Minimizing Risk of Infection. Hair near the wound usually creates minimal difficulty during repair. Shaving the hair in the area of the wound may damage hair follicles and increase risk of infection. If necessary to facilitate repair, the hair should be clipped with scissors. Alternatively, petroleum jelly can be used to keep unwanted scalp hair away from the wound while suturing. Hair over the eyebrows should never be removed because this may lead to abnormal or slow regrowth.

It is essential to clean the wound periphery at the time of wound evaluation. Povidone–iodine solution (a 10% standard solution) is often used because it is a safe and effective antimicrobial with little tissue toxicity. This solution may be diluted with saline 1:10 to create a 1% solution. Use of chlorhexidine or povidone–iodine surgical scrub preparations, hydrogen peroxide, or alcohol in the wound itself is not recommended. These may be irritating to tissues and may injure white cells, increasing the risk of infection.

Wound irrigation is extremely important to reduce bacterial contamination and prevent subsequent infection. It is often necessary to anesthetize the wound before thoroughly cleansing. Using universal precautions, the wound should be irrigated with normal saline, approximately 100 mL per cm of laceration. More may be needed if the wound is unusually large or contaminated. Use a large syringe (20 to 60 mL) with a splash-guard (commonly 20-gauge bore) attached to the end to reduce splatter during the irrigation. With the splash-guard just above the skin surface, the clinician should apply firm pressure to the plunger. This technique is usually capable of generating 5 to 8 lb per square inch (PSI) which is considered ideal pressure for wound irrigation. Some institutions may have splash-guards that attach directly to the bottle of saline. Consider warming the saline before irrigation because this may be more comfortable. Tap water has been used instead of saline, and is equally effective at irrigating wounds without increasing risk for infection. Soaking the injured body part should be avoided because this may lead to maceration of the wound and edema.

Scrubbing the wound should be reserved for particularly “dirty” wounds in which contaminants are not effectively removed with irrigation alone. Use topical or infiltrative anesthetics for pain control before scrubbing. It may be necessary to extract some foreign material with fine forceps if it remains adherent after copious irrigation. This will avoid tattooing of the skin and reduce the risk of infection.

In rare cases, the wound must be extended with a scalpel to allow proper exploration and cleaning. The physician should consider trimming small amounts of tissue in irregular lacerations and excising necrotic skin but should not make dramatic changes in the wound. Devitalized tissue should be removed only if it looks ischemic or is otherwise clearly indicated. If more extensive debridement is deemed necessary, consultation with a surgical specialist is recommended. Subcutaneous fat can be safely and easily removed if it interferes with wound closure. It is wise to remove such fat carefully, in small quantities, to avoid disruption of small vessels and cutaneous nerve branches. Avoid removal of facial fat because this may leave an unsightly depression. Debridement is advantageous because it creates well-defined wound edges that can be more easily opposed. However, excessive removal of tissue can create a defect that is difficult to close or may increase tension at the wound margin such that scarring is more likely.

Examine the wound further after cleansing and debridement. After exploration, it is wise to reevaluate the decision to close the wound primarily. When proceeding further, the emergency physician should wash hands before donning sterile gloves. Although some studies report no increased risk of infection with nonsterile gloves, most still recommend using latex free, nonpowder, sterile gloves for wound repair. Sterile masks do not reduce the risk of wound infections, but a facial splash-shield is useful to protect the clinician. The area surrounding the wound should be appropriately draped before wound repair. However, if a young child is particularly upset by facial drapes, they can be omitted. Proper cleaning of the wound is more important to uncomplicated healing than meticulous attempts to avoid introduction of small numbers of bacteria by preserving a sterile field.

Type of Suture/Equipment. Suture material must have adequate strength while producing minimal inflammatory reaction. Nonabsorbable sutures such as monofilament nylon (Ethilon) or polypropylene (Prolene) retain most of their tensile strength for more than 60 days and are relatively nonreactive. Thus, they are appropriate for closing the outermost layer of a laceration. With nylon, it is important to secure the knot adequately with at least four to five throws per knot. Polypropylene is useful for lacerations in the scalp or eyebrows because it has a blue color that is more visible and thus easier to remove, although it has memory and therefore is somewhat more difficult to control while suturing. Silk is rarely used because of increased tissue reactions and infection.

Absorbable sutures are also used in some wounds. Absorbable synthetic sutures such as dexon, monocryl, or vicryl should be used in deeper, subcuticular layers. These materials may elicit an inflammatory response and may extrude from the skin before they are absorbed if they are placed too close to the skin. When subcuticular sutures are used, they should be placed on the deeper surface of the dermis, and epithelial margins may be approximated with either tape strips or cuticular sutures. Synthetic absorbable sutures are less reactive than chromic gut and retain their tensile strength for long periods, making them useful in areas with high dynamic and static tensions. Absorbable sutures are also advantageous for intraoral lacerations. Some recommend using rapidly absorbable sutures (fast-absorbing gut) for skin closure of facial wounds in children to avoid the need for subsequent suture removal. Equally acceptable cosmetic results are found with absorbable sutures compared with nonabsorbable sutures in pediatric facial laceration repair. Some hand specialists also advocate for absorbable sutures for hand lacerations in young children since removing them can be quite difficult in uncooperative young patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree