MINOR LESIONS

SARITA CHUNG, MD

GOALS OF EMERGENCY CARE

A variety of minor lesions in children may prompt an emergency department (ED) visit. Most visits are the result of acute injury, infection, or combination of the two mechanisms (e.g., hair tourniquet, felon paronychia). Some formerly quiescent abnormalities (e.g., thyroglossal duct cyst, pyogenic granuloma) become clinically apparent after rapid enlargement secondary to infection or direct trauma. Alternatively, asymptomatic minor lesions (e.g., lipoma, pilomatrixoma) may be noted during the evaluation of an unrelated complaint. Regardless of the presentation, a systematic approach is necessary for proper diagnosis and subsequent management of these lesions. Although most “lumps and bumps” in children have a benign cause, the examiner should bear in mind the possibilities of associated systemic illness and future complications.

RELATED CHAPTERS

Signs and Symptoms

Medical, Surgical, and Trauma Emergencies

• Dermatologic Urgencies and Emergencies: Chapter 96

• Endocrine Emergencies: Chapter 97

• Infectious Disease Emergencies: Chapter 102

• ENT Emergencies: Chapter 126

HAND AND FOOT LESIONS

CLINICAL PEARLS AND PITFALLS

• Herpetic whitlow involving a finger is sometimes mistaken for a paronychia

• Consider hair tourniquets in the crying infant

• Ganglion cysts should not be ruptured in the ED but may require outpatient excision if painful or cosmetically concerning

• Trephination is treatment of choice for uncomplicated subungal hematomas with intact nail margins regardless of the size of the hematoma

Eponychia and Paronychia

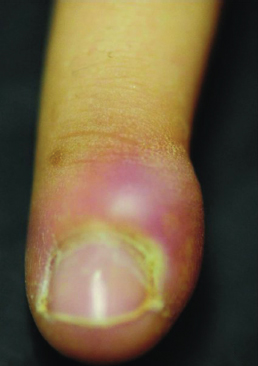

Infections and/or minor trauma of the digits are the major etiologies of hand lesions in the emergency department (ED). The most common infections of the digits involve the eponychium (cuticle) as a result of a breakdown of the epidermal border due to trauma such as a traumatized hangnail or, particularly in children, finger sucking or nail biting. In its initial stage, the infection consists of a superficial cellulitis that remains localized to the cuticle and is termed an eponychia. Symptoms include erythema and localized pain at the nail margin. With progression, pus collects in a single thin-walled pocket under the cuticle, forming an acute paronychia (Fig. 128.1). Patients typically present with localized tenderness and have an area of fluctuance and purulence around the nail margin. This may progress, extending under the skin at the base of the nail, and along the nail fold. Less commonly, the pus burrows beneath the proximal nail, forming an onychia or subungual abscess. Causative organisms include Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, and anaerobic species. Chronic paronychia can be seen in patients repeatedly exposed to water or moist environments. Symptoms are present for weeks and are similar to those with acute paronychia. Eventually, the nail may become thickened and discolored. Candida albicans is the most frequent organism seen with chronic paronychia.

Treatment of a simple eponychia involves frequent warm soaks and attention to local hygiene. Topical antibacterial ointments may hasten resolution. Treatment of an acute paronychia is incision and drainage (Chapter 141 Procedures). If an onychia has formed, removal of the proximal portion of nail overlying the abscess is essential to ensure adequate drainage and prevent destruction of the germinal matrix. When an onychia forms under the anterolateral aspect of a nail, treatment consists of elevation and excision of the overlying portion of the nail. The role of oral antibiotics after incision and drainage has not been clearly established but does represent common practice. If the infection is due to finger biting or sucking, antibiotics providing coverage against anaerobes should be considered. Oral antimicrobial therapy is indicated for patients with associated lymphangitis. Coverage for methicillin-resistant S. aureus should be considered if there is clinical suspicion, high rate in the community or the infection is not improving. Treatment of chronic paronychia consists of topical steroids and/or antifungal agents.

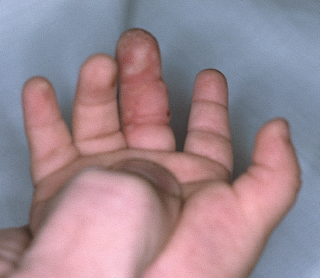

Herpetic Whitlow

A herpetic whitlow involving a finger is sometimes mistaken for a paronychia and is the major differential diagnostic consideration. The majority of cases are in children younger than 2 years. Clinically, this lesion is characterized by the appearance of multiple, painful, thick-walled vesicles on erythematous bases most commonly located at the pulp space of the digits but can also occur around the nail folds and lateral aspects of the digit. During the ensuing few days, vesicles begin to coalesce and their contents become pustular (Fig. 128.2). A Gram stain of pustular fluid is negative for bacteria. If a Tzanck prep of scrapings from the base of a lesion is performed, it will reveal multinucleated giant cells. Subsequently, ulceration and crusting occur. The process initially results from inoculation of herpes simplex virus into a small break in the skin. The source may be a parent with herpes labialis, or a child with herpetic gingivostomatitis or herpes labialis may inoculate his or her own finger. With primary infection, fever and regional adenopathy are seen. With recurrences, these findings are usually absent.

FIGURE 128.1 Paronychia of the finger. (From Salimpour RR, Salimpour P, Salimpour P. Photographic Atlas of Pediatric Disorders and Diagnosis, 1st ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2013.)

The course is usually self-limited. However, oral acyclovir may be given in the first few days of the infection to shorten the course. For the immunocompromised patient, parenteral acyclovir should be considered to prevent dissemination. A complication of herpetic whitlow is bacterial superinfection.

FIGURE 128.2 Herpetic whitlow. (From Fleisher GR, Ludwig W, Baskin MN. Atlas of Pediatric Emergency Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004.)

Felon

A felon consists of a deep infection of the distal pulp space of a fingertip. Felons are caused by introduction of bacteria into the pulp space, usually by punctures (which may be trivial) or splinters. Causative organisms are similar to those found in eponychial infections. A felon typically presents as an exquisitely tender and throbbing fingertip that is swollen, tense, warm, and erythematous. However, its evolution is usually relatively slow, beginning with mild pain and minimal swelling that progress over a few days. This process is in part caused by the anatomy of the pulp, which consists of multiple closed spaces formed by fibrous septae that connect the volar skin to the periosteum of the distal phalanx. With progression of infection, pressure buildup within these small compartments may cause local ischemia. In some cases, organisms may spread to invade the phalanx, resulting in osteomyelitis. In others, the process may point outward to the center of the touch pad, where the septae are least dense, producing an obvious area of fluctuation. Because the deep septal attachments are distal to the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint and flexor tendon sheath, there is less risk of spread to these structures.

Treatment consists of incision, blunt dissection, and drainage. Digital blocks are favored for analgesia. A longitudinal incision over the area of maximal tension or fluctuance is the procedure of choice. If swelling is greatest laterally, an incision along the ulnar surface of the second through fourth digit or radial side of pinky or thumb may be preferred. Care should be taken to extend the incision past the DIP joint to prevent formation of a flexion contracture (see Chapter 141 Procedures). After drainage, a course of oral antibiotics is indicated. Close follow-up is essential to assess response to therapy and identify complications, such as septic arthritis and suppurative tenosynovitis. A hand specialist should be consulted for patients presenting with fever, lymphangitis, or evidence of osteomyelitis for admission, parenteral antibiotics, and definitive care.

Subungual Hematoma

A subungual hematoma is a collection of blood located under a nail that arises after trauma to the nail bed, typically due to a crush injury. Because this mechanism is also a common cause of phalangeal fractures, radiographs are advisable. The patient experiences throbbing pain that worsens with increasing pressure as more blood collects. If the subungual hematoma involves more than 50% of a nail surface, is associated with a distal phalanx fracture, or the nail or its margins are disrupted, the presence of a significant nail bed injury should be suspected. Nail trephination provides drainage with relief of pressure and pain. This procedure also reduces risk of secondary infection. This treatment alone suffices for uncomplicated subungual hematomas with intact nail margins, regardless of size of the hematoma. The trephined opening should be large enough (larger than 3 to 4 mm) to allow for ongoing drainage without risk of closure by a new clot. Sometimes producing two openings in the nail will promote more complete drainage (see Chapters 117 Hand Trauma and 141 Procedures). When the nail or its margins are disrupted and/or a displaced phalangeal fracture is present, the nail should be removed and the nail bed repaired. Antimicrobial prophylaxis for these injuries remains a source of controversy but is often prescribed for patients with underlying fractures and those with severe soft-tissue injuries.

Subungual Foreign Body

Foreign bodies such as a wood splinter or metallic shaving become embedded under the nail and may be the source of pain and/or infection. When the foreign body is only partially embedded, the nail can be trimmed close to the nail bed, and the object’s projecting end grasped with splinter forceps and gently extracted. If a portion remains or the foreign body is deeply embedded from the outset, a digital block should be performed. Then the part of the nail overlying the object can be shaved down with a scalpel until the foreign body is exposed. Alternatively, the nail can be lifted and the object removed (see Chapter 141 Procedures). After splinter removal, the finger should be soaked in warm, soapy water, and an antibiotic ointment and protective dressing applied. Soaks should be repeated three times daily at home for the ensuing 3 to 5 days. In the unusual case of a child with multiple subungual splinters or fragments, it is best to remove the nail, clean out the foreign material, irrigate thoroughly, and then replace the nail (after trephining it to allow drainage).

Hair Tourniquet

A hair tourniquet injury is unique to pediatrics. It involves strangulation of a digit (or occasionally genitalia) by a hair or fine thread. It is seen most commonly in young infants and can be the cause of unexplained irritability or crying. The mechanism involves entwinement of the hair around an infant’s digit. This may occur during a bath, or as a result of wiggling of the toes in a sock, bootie, or mitten that inadvertently has a hair or loose thread in it. A hair shed from a parent during diapering is the probable source of penile tourniquets. As the hair or thread becomes more tightly entwined, it produces a tourniquet effect, impairing blood flow with resultant ischemic pain and distal swelling. When noted early, the hair is often visible in a crease just proximal to the swollen area. If seen later, the hair may have cut through the skin, making it difficult to visualize (Fig. 128.3). In rare cases, frank ischemic necrosis of the distal digit may be seen on presentation. Removal requires a fine-tipped forceps and the aid of a thin loupe or probe that is inserted proximally under the constricting hair. Usually the hair can be unwound from the digit intact or cut with scissors. When the hair is deeply embedded or there is any question of a remaining constricting band, a nerve block should be performed and a perpendicular incision made over the hair. To avoid damage to neurovascular structures, such an incision should be made on the lateral or ulnar aspect of a finger or toe at 3 or 9 o’clock or at 4 or 8 o’clock along the penile shaft. When the entire hair cannot be removed with certainty, consultation with a plastic surgeon is indicated.

FIGURE 128.3 Hair tourniquets. (From Fleisher GR, Ludwig S, Baskin MN. Atlas of Pediatric Emergency Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004.)

Ganglion

A ganglion is a cystic outgrowth or protrusion of the synovial lining of a tendon sheath or joint capsule. Common locations of ganglions include the dorsal or volar surface of the wrist (usually on the radial side), the dorsum of the foot, and near the malleolus of an ankle (Fig. 128.4). Occasionally, a flexor tendon sheath ganglion may present on the palmar surface of the hand at the base of a digit. The cause is believed to involve prior trauma that causes partial disruption of the synovium and subsequent herniation of synovial tissue. The cysts are soft, slightly fluctuant, and transilluminate. Most are painless or only mildly uncomfortable. However, those on the foot or ankle may cause pain when shoes are worn. Elective surgical excision with obliteration of the base is indicated only if function is impaired or the lesion is of cosmetic significance. Even then, up to 20% recur. Striking the cyst with a heavy object, an old fashion folk remedy, should be strongly discouraged because the cystic fluid may be dispersed through the surrounding soft tissue, inciting diffuse scar formation.

FIGURE 128.4 Ganglion cyst. (From Salimpour RR, Salimpour P, Salimpour P. Photographic Atlas of Pediatric Disorders and Diagnosis. 1st ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2013.)

FACE AND SCALP LESIONS

CLINICAL PEARLS AND PITFALLS

• Epidermal inclusion and dermoid cyst are slow-growing nonmalignant painless lesions

• Superinfected cysts or congenital lesions may undergo incision and drainage and are treated with antibiotics before complete excision is recommended

Epidermal Inclusion Cyst

Among the most common postpubescent skin lesions is the epidermal inclusion cyst (EIC). These have also been termed epithelial, sebaceous, and pilar cysts. Most result from occlusion of pilosebaceous follicles, although some stem from inoculation of epidermal cells into the dermis via needlestick or other trauma. A few may arise from epidermal cells that become trapped along embryonic lines of closure. Lesions consist of firm, slow-growing, 1- to 3-cm, round nodules. Most are solitary lesions found about the scalp and face, although they also may be located on the trunk, neck, and scrotum. Histologically, these dermal and subcutaneous nodules consist of epidermally lined keratin-filled cysts. Presentation is that of a slow-growing painless lump that may provoke concerns of malignancy. At times, these cysts become acutely infected, and the patient complains of pain, erythema, and sudden increase in size. Infected cysts should be incised and drained, as well as treated with oral antibiotics before elective excision. Noninflamed cysts can be referred for elective excision that must include the entire sac to prevent recurrence.

When a patient presents with multiple large EICs, Gardner’s syndrome should be suspected. This autosomal dominant disorder is characterized by multiple EICs, intestinal polyposis, desmoid tumors, and osseous lesions. Early diagnosis is especially important because of a 50% risk of malignant transformation of the intestinal polyps.

Dermoid Cyst

Dermoid cysts are congenital, subcutaneous nodules derived from ectoderm and mesoderm. There is a male predominance. They, too, are lined with epithelium, but unlike EICs, they may contain multiple adnexal structures such as hair, glands, teeth, bone, and neural tissue, as well as keratin. The cysts usually present as solitary, round, firm nodules with a rubbery or doughy consistency on palpation, a smooth surface, and normal overlying skin. Lesions tend to grow slowly, and malignant transformation is rare. Whereas some dermoids may be mobile, many are fixed to overlying skin or underlying periosteum. Occasionally, dermoids may have deeper attachments extending intracranially or intraspinally, along with an accompanying sinus. Because these cysts form along areas of embryonic fusion, common sites include the nasal bridge, midline neck, or scalp; the lateral brow (Fig. 128.5); anterior margin of the sternocleidomastoid; and midline scrotum or sacrum. An external ostium may or may not be visible. A small percentage of patients with dermoid cysts may have other craniofacial abnormalities. Because the sinus tract can serve as a conduit for spread of secondary infection, all midline lesions should have appropriate imaging (computed tomography [CT] and/or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) followed by elective excision.

Nasal Bridge Lesions

Midline nasal masses in infants and children may be acquired (e.g., EIC) or congenital, the latter stemming from improper embryologic development (e.g., dermoid cyst, encephalocele, glioma).

FIGURE 128.5 Dermoid cyst abscess. (From Fleisher GR, Ludwig W, Baskin MN, eds. Atlas of pediatric emergency medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004. Reprinted with permission.)

Dermoids are the most common embryologically derived midline nasal lesions (see previous discussion). Clinically, a firm, round, subcutaneous mass is seen in the midline over the dorsum of the nose. Some have an overlying dimple, which may have an extruding hair (Fig. 128.6). Its attachment may extend only to the nasal septum or may go deeper through the cribriform plate into the calvarium. Because of their proximity to the nasopharynx, these dermoids are particularly prone to secondary infection and fistula formation. Hence, prompt excision is indicated after careful MRI or CT.

Gliomas are benign growths composed of ectopic neural tissue. The lesion usually consists of a firm, gray, or red–gray nodule, ranging in size from 1 to 5 cm and can be mistaken for a hemangioma. Most are extranasal (60%), occurring on the bridge of the nose. The remainders are either solely intranasal masses (30%) or have both intranasal and extranasal elements (10%). By definition, they do not have intracranial communication. They are composed of neural and fibrous tissue, covered by nasal mucosa. There is a male predominance. To prevent possible distortion of surrounding bone and cartilage, surgical excision is the treatment of choice.

FIGURE 128.6 Preauricular surface pit. (Courtesy of David Tunkel, MD. In: Chung EK, Atkinson-McEvoy LR, Lai NL, et al., eds. Visual Diagnosis and Treatment in Pediatrics. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health, 2014.)

Encephaloceles consist of neural tissue that has herniated through a congenital defect in the midline of the calvarium, and thus, always have an intracranial communication. Lesions appear as soft, at times pulsatile, compressible masses that enlarge with crying or straining. Compression of the jugular veins (Furstenberg test) may also cause the mass to expand in size. Some infants with nasal encephaloceles are born with overt craniofacial deformities and a rounded swelling at the base of the nose, whereas in others, the mass is confined to the nasopharynx, and external facial features are normal. The latter may present with signs of persistent nasal obstruction. In these patients, a grapelike mass is found on nasopharyngoscopy. MRI is the modality of choice for differentiating encephaloceles from other midline nasal masses and for determining their size and extent. Neurosurgical evaluation and management is indicated for all encephaloceles.

Preauricular Lesions

Preauricular lesions, located just anterior to the tragus, may be the result of imperfect fusion of the first two branchial arches (sinus tract, pit) or may consist of first arch remnants (cutaneous tag). They may be unilateral or bilateral, single or multiple. Usually, they are seen as isolated minor anomalies, but on occasion they can be found in association with other developmental anomalies involving the first branchial arch or in infants with chromosomal disorders. Most lesions are evident shortly after birth. Some individuals simply have a surface pit or dimple, whereas in others, the overlying dimple represents the entrance to a sinus tract or blind pouch with a small cyst at its base (Fig. 128.6). The latter may contain hair and other epidermal elements. Sinuses are prone to infection and abscess formation, whereupon the child presents with sudden enlargement of a painful preauricular mass and overlying erythema. When this occurs, the patient should be treated with appropriate antimicrobial therapy before elective excision of the cyst and fistula tract. Cutaneous tags, also called accessory auricles, are flesh-colored pedunculated lesions that may or may not have a cartilaginous component (Fig. 128.7). Some with narrow bases may simply be tied off with silk sutures. Those with wider bases and those containing cartilage can be referred for elective excision for cosmetic reasons.

NECK LESIONS

CLINICAL PEARLS AND PITFALLS

• Parotitis is most commonly viral, and treatment involves supportive care including (citric or sour) food to facilitate salivary flow.

• Avoid incision and drainage of facial abscesses near the ramus of the mandible, as they may represent an infected first branchial cleft remnant.

• When torticollis is associated with a neck mass, sternocleidomastoid tumor (fibromatosis colli) should be considered in infants.

• Posterior triangle and supraclavicular masses carry a much higher risk for neoplasm than do anterior triangle masses.

• Consider treatment for methicillin resistant S. aureus in acute lymphadenitis if the infection is not improving after treatment or there is a high prevalence in the area.

• Consider an evaluation for pyriform sinus fistulas in children with acute suppurative thyroiditis.

FIGURE 128.7 Multiple preauricular skin tags. (Courtesy of David Tunkel, MD.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree