INTRODUCTION

Care for combat casualties is somewhat different from care for civilian trauma casualties, even though many civilian trauma management principles apply, and conversely, some military techniques have been adapted to the civilian sector. The principles of military medical care are applicable to care in civilian mass casualties, in remote settings, for tactical medicine, and in bioterrorism incidents. Civilian emergency medicine should regularly follow military medical advances and adapt as appropriate.

Advanced trauma life support approaches are well applied in a hospital setting, but in combat, how do you function without ancillary staff? What do you do without ready access to a surgical team? How will you manage in the dirt, at night, while engaged with enemy forces? Simple tasks such as obtaining vital signs or auscultating lung sounds are very challenging. Chapters 7, “Bomb, Blast, and Crush Injuries,” 8, “Chemical Disasters” and 9, “Bioterrorism,” discuss many conditions relevant to the combat situation. Table 302-1 lists the roles of medical care for combat casualties.

| Role 1: self/buddy aid, nonmedical unit level combat lifesaver, medic or corpsman aid up to battalion aid station |

| Role 2: brigade or division level, medical companies/battalions, support battalions, forward surgical teams, PRBCs, limited x-ray and lab capability, damage control care for evacuation to next role |

| Role 3: corps level, combat support hospitals, in-theater military treatment facility (MTF), comprehensive stabilizing care for evacuation out of theater |

| Role 4: definitive care, ultimate treatment capability, full rehabilitative care, tertiary care MTF, typically located in continental United States or comparable out-of-theater safe havens |

EQUIPMENT

Combat situations require a properly supplied aid bag. A blood pressure cuff and central-line kit have little use on the battlefield. Pack one item that serves multiple purposes, rather than two or three items with limited applications. For example, a cravat can be used as a standard field dressing, pressure dressing, or tourniquet or to hang an IV bag, cover a face as a dust mask, protect against sun exposure on head or neck, filter parasites from water, or even clean weapons.

See Tables 302-2 and 302-3 for examples packing list for aid bags. Not all items will be needed or packed in one bag; the nature of the mission, duration, terrain, weather, and other factors guide the packing list. Consider maintaining two or more different packing lists for different purposes (i.e., one for battle injuries and one for nonbattle injuries).

| Combat Application Tourniquet (Composite Resources, Rock Hill, SC) or equivalent (× 4–5) or Delfi EMT tourniquet (Delfi Medical Innovations, Inc., Vancouver, Canada) (× 1) | 3-inch self-adherent elastic roll dressing × 4 (open package and pre–dog-ear exposed end for rapid utilization) |

| Examination gloves, heavy duty, four pairs | Hemostatic bandage (4 × 4 bandage) × 4 |

| Protective ballistic eye wear | Large abdominal dressing (can also be used to stabilize flail chest segments) |

| Cervical collar, adjustable | Surgical skin stapler† (for rapid hemostasis of scalp lacerations) |

| Nasopharyngeal airway with water-based lubricant packet × 2 | IV fluid administration kits × 2–3 |

| Hypothermia prevention and management kit | 500 mL Hextend × 2 |

| Cricothyrotomy kit* | 500–1000 mL colloid or crystalloid IV solution (250–500 mL bags) |

| Betadine swab | 16-, 18-, and 20-gauge IV catheters |

| No. 20 scalpel | IV administration set, 10 drops per mL |

| Tracheal hook | Penrose drain or other tourniquet |

| No. 5 or 6 Shiley tracheostomy tube | Betadine wipe × 2 |

| Securing tape or strap | Benzoin swab × 2 (aids dressing adherence in the presence of sweaty or bloody skin) |

| Endotracheal intubation kit† | |

| AA battery laryngeal scope handle | 1-inch tape, short roll |

| Physician’s preference of laryngeal scope blade | Clear IV site dressing (Tegaderm) |

| 7.5-mm endotracheal tube | 2 × 2-inch gauze |

| Stylette | 5-mL syringe (for external jugular vein placement) |

| 10-mL syringe | Saline lock |

| Carbon dioxide colorimetric indicator or esophageal bulb indicator | 1 m of string, 550 paracord or cravat prefolded and taped (to expediently hang IV bag) |

| Carabiners/D ring × 2 | Thermal angel or equivalent fluid warmer |

| Benzoin swabs | IO infusion system (sternum IO device) |

| 1-inch tape | Pressure infuser bag |

| Oropharyngeal airway | Combat wound prophylaxis kit (3 medication pack) |

| Skin marker (to mark centimeters at the teeth on cheek to confirm tube placement during transport) | Wound antibiotic of choice × 3 doses (see section on antibiotics for options) |

| 10-mL sterile water or normal saline vial × 3 | |

| Adult bulb suction device such as Suction Easy (Remote Medical International, Seattle, WA) | 10-mL syringe × 3 21-gauge needle 1.5 inch long × 3 |

| Adult bag-valve mask | Gatifloxacin, 400-milligram tablets × 6 |

| 3 inch long 12-gauge catheter × 2 (decompressing tension pneumothorax in large adults) | Rocephin, 1-gram vial × 1 (CNS wound prophylaxis) Combat wound pain control kit |

| Adhesive one-way flutter valve/seal × 2–4 with benzoin swabs (sucking chest wound dressing with valve) | Cartridge unit (syringe holder to create a drug delivery system) Morphine, 10-milligram cartridge ampules × 5–10 |

| Finger pulse oximeter | Nalbuphine hydrochloride, 10-milligram cartridge ampules × 3† |

| Stethoscope | 19-gauge filter needles × 3† |

| Trauma shears | 1-mL syringes × 3† |

| Field tube thoracostomy kit† | 21-gauge needle 1.5 inch long × 3† |

| 1% lidocaine with epinephrine, 10-mL vial | Acetaminophen, 500-milligram capsules × 10 |

| 10-mL syringe | Narcotics accountability paperwork with pen |

| 1.5-inch 21-gauge needle | Cravat bandage × 3 |

| Sterile gloves | SAM (structural aluminum malleable) splint (SAM Medical Products, Portland, OR) × 2 |

| Betadine swab × 3 | 4-inch elastic wrap × 2 |

| No. 10 scalpel | Gastric sump tube with water-based lubricant packet |

| Large curved Kelly forceps | 60- or 35-mL syringe |

| 32F–36F thoracostomy tube | Light-emitting diode headlamp with green lens filter (red filter will “wash out” blood) |

| Heimlich chest drain valve (or Penrose drain) | Mass casualty patient cards |

| 0 silk (30 inches long) on a straight needle (needle driver not required to secure tube) | Red, green, blue, yellow safety light sticks (five of each) |

| 3 × 18-inch Vaseline gauze | Fine-point indelible marker |

| 4 × 4-inch gauze × 2 | Fox eye shield |

| Benzoin swabs | Small sharps container |

| 3-inch 3M Soft Cloth Surgical tape (3M, St. Paul, MN), one roll (appears to stick to bloody, sweaty patients better than most) | Large burn dressing (consider a roll of plastic cling wrap) Compact casualty blanket |

| 6-inch Israeli Battle Dressings (First Care Products, Lod, Israel) × 4 | Folding litter† |

| Kerlix large roll dressing (Covidien, Mansfield, MA) × 4–8 | Compact traction splint† |

Light-emitting diode headlamp with green lens filter Combat Application Tourniquet (Composite Resources, Rock Hill, SC) or equivalent × 2 Examination gloves heavy duty (one pair) Nasopharyngeal airway 32F Compact percutaneous cricothyrotomy device (Lifestat device; French Pocket Airway, Inc., New Orleans, LA) Trauma shears or rescue knife Adhesive one-way flutter valve/seal × 2 with benzoin swabs 12- or 14-gauge 3 inch long catheter 6-inch Israeli Battle Dressing × 2 Kerlix Large Roll dressing (Covidien, Mansfield, MA) × 2 3-inch 3M self-adherent elastic roll dressing (open package and pre–dog-ear exposed end) 1-inch medical tape, one roll 9-line medical evacuation card |

Have a copy of the nine-line medical evacuation request secured to the radio, train on your personal equipment, maintain it, and pack smartly to ensure easy access to critical items.

TACTICAL COMBAT CASUALTY CARE

The body of highly developed, standardized, prehospital combat trauma guidelines designed to address prevenTable causes of death is known as Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC), which is organized into three phases of care: care under fire, tactical field care, and casualty evacuation.

This first phase of care occurs when the patient and care provider are under effective enemy fire. The medical actions taken are extremely limited: protect the casualty and move him or her to safety. The urge to tend to a casualty must be tempered by situational awareness: return fire, and secure the site before tending to casualties. The application of a tourniquet for massive bleeding is the only intervention typically performed in this phase (also see “Tourniquets,” in chapter 254, “Trauma in Adults”). Needle decompression, fluid resuscitation, and cervical spine immobilization are not performed when under fire.

With massive hemorrhage in a combat setting, a tourniquet is the first-line intervention.

Casualties with tourniquets applied before the onset of shock have a survival rate of 94%, but those with tourniquets applied after shock develops have a survival rate of 17%.1,2

There are a number of basic considerations for tourniquet application.3 A wide tourniquet (at least 1.5 inches wide) causes less soft tissue damage and is more comforTable for the patient. To control hemorrhage from a large vessel, a tourniquet must have a windlass to gain a mechanical advantage when tightening. Tourniquets without a windlass cannot attain sufficient force to stop arterial bleeding. In combat, we use a tourniquet that can be applied with one hand for self-treatment.

Place the tourniquet about 2 inches proximal to the wound. Tighten to greater than arterial pressure, because tightening that exceeds venous but not arterial pressure may increase bleeding. Apply the tourniquet until the distal pulse disappears. If no distal pulse is present on initial evaluation, apply the tourniquet with a force estimated to be greater than the systemic blood pressure. If placement of a single tourniquet does not control bleeding, place a second tourniquet immediately adjacent and proximal to the first.

The U.S. Army Institute of Surgical Research (http://www.usaisr.amedd.army.mil) has identified three 100% effective tourniquets4: the Combat Application Tourniquet® (CAT) (Composite Resources, Rock Hill, SC), the Delfi EMT Pneumatic Tourniquet (EMT) (Delfi Medical Innovations, Inc., Vancouver, Canada), and the Special Operations Forces Tactical Tourniquet (SOFTT). The CAT and SOFTT are both strap tourniquets that use a built-in windlass as the mechanism for tightening (see Figures 254-1 and 254-2). Of these two strap-type tourniquets, the CAT is less painful, easier to use, smaller, and lighter than the SOFTT (59 grams vs 160 grams). The EMT (see Figure 254-3) is wider, less painful, and less likely to induce nerve damage than the strap tourniquets. The EMT weighs 215 grams and, when packaged, is similar in size to the SOFTT. The CAT tourniquet is standard issue to U.S. military personal. The EMT tourniquet is issued for medical evacuation vehicles and role I to III medical facilities. All of these tourniquets are available through the military medical supply system (http://www.usamma.army.mil/).

The safe time limit for tourniquet application and the point at which limb loss becomes ineviTable have not been determined. Tourniquets are routinely left in place for up to 2 hours in the operating room, and this is the basis for the recommendation to remove a tourniquet within 2 hours, situation permitting. It is certain that for every minute of tourniquet application time, the greater is the chance for permanent damage.5 At 6 hours with a tourniquet in place, it is probably best not to remove it; at this point, the release of potassium, lactate, myoglobin, and other toxins from a severely acidotic limb into the circulation would likely cause more systemic harm than benefit. There are, however, several cases of limb salvage with tourniquet times greater than 6 hours.6 Additionally, keeping a limb with tourniquet cool, but not freezing, may extend the safe application time substantially.

A tourniquet is a temporizing measure. The next step is to convert the tourniquet to an effective pressure dressing, using direct pressure and a basic gauze roll and elastic wraps and/or hemostatic agents, if required. A knee or hand can apply additional pressure to the bleeding site. Once an effective pressure dressing is applied, release but DO NOT REMOVE the tourniquet. If no bleeding occurs, leave the tourniquet in place but with all pressure released. If bleeding recurs, retension the tourniquet to control bleeding.

This phase begins once the patient and provider are no longer under effective enemy fire. Conduct a complete primary survey and perform life-saving interventions.

Combat medicine deviates from the universally accepted airway, breathing, and circulation (ABC) algorithm. Massive hemorrhage is the most common correcTable cause of death on the battlefield, and lethal exsanguination can occur in minutes. Airway compromise accounts for relatively few combat deaths, and respiratory difficulties typically progress over time. This is the reason that TCCC recommends the modified primary survey algorithm of MARCH:

Massive hemorrhage

Airway

Respiratory

Circulation

Hypothermia prevention/Head injury

After hemorrhage control, the algorithm mirrors the ABC algorithm, with the additional consideration of a closed head injury and hypothermia prevention as primary survey responsibilities. If a problem is noted during any part of the algorithm, it is addressed before moving further down the algorithm.

In a tactical setting, simple parameters such as level of consciousness and pulse strength are indicators of peripheral perfusion. Is the casualty verbally responsive? If yes, you have already gathered critical information: the blood pressure is strong enough to provide a modest level of cerebral perfusion, and the airway is patent. If the soldier’s peripheral pulse is weak or absent, level of consciousness is altered, or if not verbally responsive, then immediate intervention is needed before moving down the algorithm.

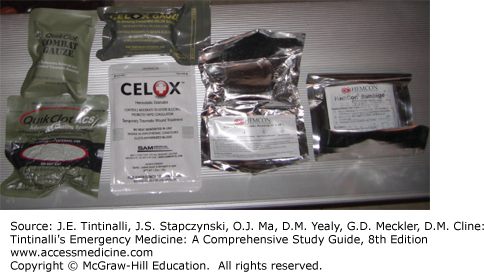

Topical Hemostatic Agents If the wound is not amenable to tourniquet use and a pressure dressing is inadequate, use a hemostatic agent (Figure 302-1). The TCCC Committee recommends the following agents: Combat Gauze, Celox Gauze, and ChitoGauze. Combat Gauze (Z-Medica Corporation, Wallingford, CN) uses a zeolite compound impregnated into surgical gauze, which can be easily shaped into any wound. Celox Gauze (Medtrade Products LTD, Electra House, Crewe, UK) is a chitosan-impregnated gauze, as is ChitoGauze (HemCon Medical Technologies, Portland, OR).

To apply any of these gauze-like hemostatic agents, prepare the wound by evacuating excess blood, taking care to preserve any clot that may have formed around the damaged vasculature; pack the hemostatic gauze directly over the site of the most active bleeding; repack or adjust the gauze for optimum placement; use additional hemostatic agent as required. Hold direct pressure for a minimum of 3 minutes, then reassess for bleeding and repack as needed. Secure the hemostatic agent in place with a pressure dressing.

Junctional Hemorrhage Junctional hemorrhage (from the “junctional” anatomic area between the limbs and intracavitary areas of the abdomen or thorax) is difficult to control. Hemorrhage in the axilla and groin is not amenable to tourniquet application and hemostatic agents.7 Specialized junctional tourniquets may be beneficial in certain cases. Presently these include the Abdominal Aortic Tourniquet,8 the Combat Ready Clamp,9 the Junctional Emergency Tourniquet Tool,10 and the SAM Junctional Tourniquet. Each product has specific directions for application.

Systemic Hemorrhage Control: Tranexamic Acid Tranexamic acid decreases mortality in trauma.11 It is recommended for use in all casualties that require significant fluid or blood products. Tranexamic acid is most effective when given within 1 hour of injury and must be given within the first 3 hours. The dose is 1 gram of tranexamic acid in 100 mL of normal saline.12

Prior to the Clinical Randomization of an Antifibrinolytic in Significant Hemorrhage (CRASH) study and introduction of tranexamic acid, recombinant factor VIIa was considered for use by some special operations forces.13 The advent of tranexamic acid, with its ease of administration, efficacy, and improved safety profile (the risk of systemic hypercoagulability has always been a concern), has limited the use of recombinant factor VIIa to very specific intraoperative clinical scenarios.

Airway intervention during the primary survey is similar for both combat and civilian casualties. Less than 1% of combat trauma requires lifesaving airway intervention in the prehospital setting.14,15

Lack of spontaneous respirations is a grievous prognostic sign. If there are no spontaneous respirations after opening the airway, the casualty is triaged to the expectant category (expected to die) in a mass casualty (MASCAL) situation (defined as more casualties than resources available); if the situation and resources allow, perform advanced airway techniques including cricothyrotomy,16 supraglottic airway17 intubation, and mechanical ventilation. If space is limited, cricothyrotomy equipment is the most important.31 The threshold for performing a cricothyrotomy during combat should be low. It is critical to confirm placement and firmly secure the airway.

Tension Pneumothorax The nearly universal use of body armor in present combat operations provides critical protection to the chest and upper abdomen, as evident in the 5% to 7% thoracic wound rate, the lowest in U.S. military conflicts.18 Many combatants are alive today because of the proper use of body armor.

In a tactical setting, the threshold to perform a needle decompression is very low, as most casualties with penetrating chest trauma will have some degree of hemo-/pneumothorax, and even in the absence of tension pneumothorax, needle decompression is unlikely to cause harm. Use the largest and longest catheters available, because catheters are apt to kink or occlude, and the needle will have to penetrate through several inches of muscle and soft tissue to enter the thorax. The TCCC minimum standard is the 14-gauge 3 inch long needle, as any shorter length will often not penetrate through a muscular chest.19 Also, there are 10- and 12-gauge catheters available in 3-inch lengths that are highly recommended over the standard, universally available 14-gauge catheters because they are even less likely to kink or occlude with patient movement. Two locations are recommended: (1) the second intercostal space, midclavicular line; or (2) the anterior axillary line at the fourth to fifth intercostal space (see chapter 68, “Pneumothorax,” for further discussion).20

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree