Introduction

The word “mentor” comes from Homer’s Odyssey, in which Troy—bound Odysseus entrusts his young son to the care of his close friend, Mentor. Mentor, a transitional figure in the youth’s growth, acts as the son’s guardian and wise advisor, and through their mutual relationship, the son develops his own identity. Ancient history is filled with examples of the importance of mentoring. Tradesmen in the Middle Ages were principally trained by dedicated mentors within their guilds. Chinese kings employed Shang Jang—literally, “the enlightened stepping aside to create room in the center for the next deserving person to step in and take charge”—to pass the crown to a successor.

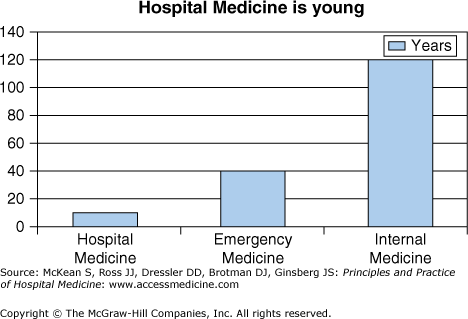

Mentoring has been vital to the art and practice of medicine since Hippocrates. Good mentors have played key roles in the history of medicine and discovery, in the development of young doctors, and in the institutions that train physicians. Today’s health care leaders point to the importance of mentoring in choice of career as well as career advancement and productivity. Yet, the available evidence shows that fewer than 50% of third- and fourth-year medical students and in some fields fewer than 20% of faculty members had a mentor.1 Academic hospitalists in particular, but also hospitalists in the community, not only serve as mentors to trainees but also to other members of the multidisciplinary team. Because Hospital Medicine is a young specialty, peer mentorship is crucial to the success of the specialty (Figure 39-1).

|

The Value of Mentoring in Medicine

Just as Mentor in the Odyssey helped the son recognize a disguised Odysseus returning from Troy, a modern day mentor can recognize previously unseen qualities in the mentee or help open doors to unnoticed opportunities. Surveys of faculty and health care leaders and one recent systematic review identified several potential benefits of mentoring in medicine. Mentoring influences career choice, including medical students’ specialty selections; promotes career advancement; increases academic productivity; develops physicians’ leadership skills; shapes professional ethics; fosters development of academic departments, institutions, and professional societies; and increases career satisfaction. Clinician-educators who receive mentoring may be more likely to stay in an academic position and view the mentoring relationship as important to academic development and promotion. The strongest evidence in support of mentoring has been demonstrated for clinician-scientists, who positively associated mentorship with scholarly productivity.

For house officers, mentoring has been promoted as one way to enhance resident satisfaction, improve career planning and readiness for future careers, and reduce stress and burnout. Medical residents clearly value mentoring. In one survey of 329 Internal Medicine house staff, 93% felt that mentoring helped in professional development, career advice, clinical assistance, research, and finding a job after residency (Table 39-1).

Benefits to the Mentee

|

Benefits to the Mentor

|

Benefits to the Department

|

While most studies have focused on half of the mentorship pair, the mentee, available literature identifies potential benefits to the mentor.

Faculty members derive personal and professional satisfaction from mentoring residents. Mentoring residents may count toward promotion, result in special awards, and possibly advance scholarly productivity.

Despite consistent reports of potential benefits of mentorships, data show that fewer than 50% of third- and fourth-year medical students and in some fields fewer than 20% of faculty members have a mentor. Clinician-educators are much less likely to identify a mentor than clinician-scientists and also less likely to serve as mentors. Despite their numbers among medical school faculty, clinician-educators account for only 28% of general internal medicine mentors. Most clinician-educator mentors volunteer for this activity and they say they already have as many mentees as they can handle. Unlike the situation for faculty researchers, objective criteria for academic advancement as a clinician-educator are wanting, and the contributions of clinician-educators have been lacking at many universities. Faculty cite competing time pressures, inadequate faculty development around mentoring, and lack of recognition of mentoring by promotions committees as factors dampening their willingness to mentor residents.

Junior hospitalist clinician-educators often worry about identifying a niche of expertise and securing time and financial support for nonclinical activities. Hospitalists have championed many aspects of the inpatient arena, including patient safety, quality improvement, resource utilization, transitions of care, surgical comanagement, and ward teaching. This jack-of-all-trades approach, while valuable to the field, can be viewed on the individual faculty level by promotions committees as “master of none.” A second tension exacerbates this problem. Hospitalist clinician-educators often cannot generate enough revenue from clinical duties to support unfunded nonclinical work, making it hard to secure protected time and financial compensation to develop expertise in education, scholarly activity, or administration.

To become more promotable, clinician-educators must ramp up their productivity during nonclinical time. The traditional clinician-educator paradigm—periods of active clinical work along with more relaxing nonclinical time—must be rethought. To paraphrase one department chair, just as diastole is now recognized as an active time of the cardiac cycle, so too must one view the nonclinical duties of clinician-educators. In some instances, clinical and nonclinical duties may overlap and provide a “two-for-one” opportunity; examples include teaching and clinical work as a ward attending, or committee work interspersed with clinical duties. For academic promotion, however, clinician-educators may need dedicated protected time and funding to support these interests. Grant funding for education research and medical school remuneration for course leadership or administrative roles provide limited support. When these resources fall short, hospitalists often turn to their division leaders for support, who in turn need to convince hospital leadership to support non-clinical activities of hospitalists.

Recent surveys at several U.S. and Canadian medical schools highlight that lack of mentoring is a powerful predictor of delays in academic advancement. Special academies in academic medicine and transparent advancement criteria for clinician-educators have recently been established to promote academic medicine as a desirable career path. Despite the benefits to faculty and trainees, less than half of internal medicine residents in 1 large survey established a mentoring relationship with a faculty member, and minority residents established mentorships much less often. House officers feared approaching senior faculty, failed to identify a mentor with similar personal or professional interests, and lacked awareness that residents could seek out mentors; only a minority felt they did not need a mentor.

Meaningful definitions of mentoring identify core elements and specific behaviors of a successful mentoring relationship while honoring the intimate and unique aspects of a given mentoring pair. A useful definition states that mentoring is a protected relationship occurring between a more advanced career incumbent (mentor) and a younger novice (mentee). Jacobi defined key elements in such a relationship.2 A mentoring relationship (1) focuses on achievement or acquisition of knowledge; (2) consists of 3 components: emotional and psychological support, direct assistance with career and professional development, and role modeling; (3) is personal in nature, involving direct interaction; (4) emphasizes the mentor’s greater experience, influence, and achievement within an organization; and (5) is reciprocal, designed to enrich the professional and personal lives of both mentor and mentee. Importantly, mentorship is not just for the most junior in the medical profession; advancing career levels present different learning needs that can be addressed through ongoing mentorship.

While most interactions occur within the workplace, many find that meals, social events, shared hobbies, and professional meetings provide additional opportunities for career guidance. The effective mentoring relationship assumes an always professional and nonsexual, rather than personal, focus; mutual trust and respect allow for disagreement. Table 39-2 illustrates the key qualities of a good mentor.

|

The best way to pair mentors with mentees is unknown. Mandatory mentor assignments engage all mentees in some form of advising, thus addressing vexing gaps in mentoring among physicians. There may be other advantages of formal mentoring programs over informal mentoring. More effective and enduring mentor-mentee relationships may result from independent partnerships.

Mentoring models include: (1) the traditional model of mentorship as a one-to-one relationship spanning an entire professional career at one academic institution, (2) collaborative group mentoring, (3) mentorship between one mentee and multiple mentors, (4) integrated peer mentoring, (5) networking at annual society meetings, (6) mentoring from a distance (telementoring), and combinations thereof. Table 39-3 reviews mentoring models and the strengths and weaknesses of each.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree