Key Clinical Questions

What symptoms are consistent with oropharyngeal versus esophageal dysphagia?

What etiologies and mechanisms lead to dysphagia?

What tests and studies are useful to evaluate dysphagia, based on symptoms and signs?

What treatments are available for each etiology of dysphagia?

What is the long-term prognosis and follow-up for dysphagia, based on the diagnosis?

Introduction

Dysphagia is caused either by lack of coordination of the muscles required to transfer food material from the mouth to the stomach or by a fixed obstruction between the mouth and the stomach.

Dysphagia is a common complaint, especially in the elderly. Fifteen percent of people older than 60 years who live independently complain of dysphagia, whereas 30–60% of residents in institutional settings experience dysphagia. Incidence and prevalence also varies according to underlying neurological problems. Various neurological disorders have increased risk of dysphagia (Table 153-1). Furthermore, dysphagia is associated with high mortality and morbidity. Patients with stroke who have dysphagia are twice as likely to die as patients without dysphagia. Several studies have also demonstrated that patients with dysphagia have higher incidence of aspiration pneumonia, longer length of hospital stay, as well as more severe levels of disability years after their stroke.

| Neurological Disorder | Incidence/Prevalence of Dysphagia |

|---|---|

| Acute cerebral infarct | 5–60% develop dysphagia acutely, but 86% of them recover after acute phase |

| Bulbar poliomyelitis | 60% have persistent long-term dysphagia |

| Parkinson disease | 15–20% have clinical symptoms of dysphagia, but 95% have silent aspiration |

| Myotonic dystrophy | 50%, have clinical symptoms of dysphagia, but 95% have silent aspiration |

| Myasthenia gravis | 30–40% have prominent dysphagia |

Pathophysiology

Swallowing is divided into three phases: the oral preparatory phase, the pharyngeal phase, and the esophageal phase. Oral preparatory phase starts with the food bolus being placed in the mouth and being chewed with the help of the muscles of mastication. From the oropharynx, the food bolus is propelled by the back of the tongue and other muscles into the pharynx, with voluntary elevation of the soft palate in order to prevent food from entering the nose. The cranial nerves involved in this stage of swallowing include the trigeminal, facial, and hypoglossal nerves.

The pharyngeal phase starts as the bolus reaches the pharynx. Special sensory receptors activate this involuntary phase of swallowing. The reflex, which is mediated by the swallowing center in the medulla, causes the food to be further pushed back into the pharynx and esophagus by rhythmic, involuntary contractions of several muscles in the back of the mouth, pharynx, and esophagus.

The esophageal phase begins with the opening of the upper esophageal sphincter. The lower esophageal sphincter relaxes and food passes into the stomach. The passage of food through the esophagus during this phase requires the coordinated action of the vagus nerve, the glossopharyngeal nerve, and nerve fibers from the sympathetic nervous system.

Dysphagia can occur when there is an abnormality in any of these phases. Based on the presenting symptoms and signs, the specific pathophysiology can be determined (Table 153-2).

| Case Presentation | Analysis | Differential Diagnosis | Pathophysiology |

|---|---|---|---|

| A 60-year-old man with past medical history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus presents to the ED with sudden onset of inability to use right arm and leg. He also has slurring of speech with difficulty swallowing. | Sudden onset of symptoms suggest a central nervous system acute event. | Cerebrovascular accident involving either MCA territory or extracranial ICA territory, multiple sclerosis, Guillain-Barre syndrome and polio | Oral preparatory and pharyngeal phases involved |

| A 45-year-old woman presents with gradual onset of difficulty swallowing. The symptoms occur a few minutes after swallowing. It is accompanied by nasal regurgitation and change in tone of her voice. She also coughs every time she tries to eat. Symptoms are preceded by difficulty climbing stairs and combing her hair. | Gradual onset of dysphagia with symptoms of muscle weakness is suggestive of an underlying myopathic cause of dysphagia. | Connective tissue disorders like dermatomyositis and polymyositis, sarcoidosis, paraneoplastic syndromes, and myasthenia gravis | Oral preparatory, pharyngeal and esophageal phases involved |

| A 30-year-old man presents with difficulty swallowing for both solids and liquids over several months. He has complaints of significant weight loss and regurgitation of undigested food several hours after eating the meal. He also has history of recurrent pneumonias. | Gradual onset of dysphagia for solids and liquids in a young individual is suggestive of esophageal dysmotility. | Diffuse esophageal spasm, ineffective esophageal motility, scleroderma, lupus, mixed connective tissue disorders, and achalasia | Esophageal phase involved |

Diagnosis

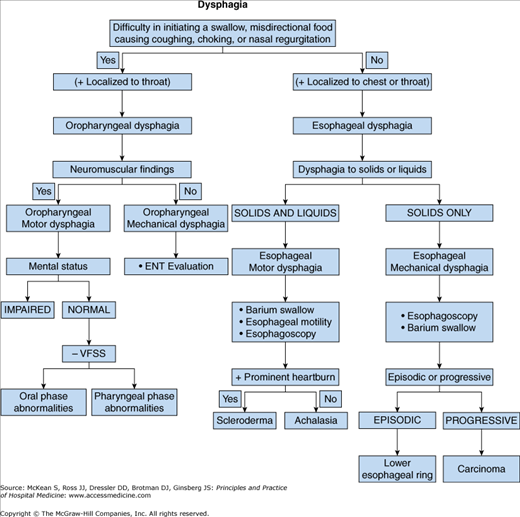

Evaluation of patients with dysphagia involves distinguishing oropharyngeal dysphagia from esophageal dysphagia during a thorough history and physical examination (Figure 153-1). In patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia, swallow initiation may be delayed or absent. Symptom onset often occurs immediately after swallowing rather than later. The patient may also express a need to reposition the body to facilitate transfer. Aspiration may manifest as cough after swallowing. Nasopharyngeal regurgitation or change in tone of speech may be reported. A sensation of fullness in neck or chest is most likely reported by patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia, but it can also be experienced in patients with GERD or esophageal dysphagia. Additionally, weight loss, nutritional deficiency, and recurrent aspiration pneumonia are common presenting problems.

The differential diagnosis for a patient presenting with dysphagia is extensive (Table 153-3). The examiner should perform a thorough physical exam, including a complete head and neck exam as well as neurological exam, to delineate between various causes of dysphagia. The presence of cervical lymphadenopathy should raise the possibility of a malignant etiology of the patient’s symptoms or upper extremity weakness and/or myopia a myopathic etiology such as myastenia gravis. Oropharyngeal etiologies of dysphagia may include iatrogenic, infectious, inflammatory, metabolic, myopathic, neurologic, and structural causes. Esophageal etiologies include reflux, infiltrative diseases, connective tissue disorders, motility disorders, and structural disorders (Table 153-3).

|

The patient’s presenting history and other clinical information should direct testing towards the most likely possibilities. Diagnostic modalities employed in the workup of dysphagia include barium swallow (modified or nonmodified), fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES), manometry, and scintigraphy (Table 153-4 and Figure 153-2).

| Diagnostic Test | Clinician Involved | Presentation Where Test Indicated | Invasiveness | Technique | Information Obtained |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modified barium swallow | Speech pathologist, fluoroscopic radiologist | Nasal regurgitation, change in tone of voice, cough with eating, recurrent pneumonia | No | Lateral and anteroposterior views of oral and pharyngeal phases of swallow are assessed by speech pathologist |

|

| Barium swallow |