Chapter 48 Mental Health Emergencies

For many reasons, the emergency department (ED) has become a frequent source of care for patients with mental health concerns. Over the past several decades psychiatric inpatient capacity has decreased. The numbers of mental health clinics and other outpatient services are insufficient to meet the needs of Americans who at any given time have a diagnosable mental illness, which ranges from 20% to 26.2% of the population.1,2

The decrease in the number of psychiatric inpatient beds and the insufficient outpatient mental health resources compound the issue of mental health care in the ED. As a recent American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) survey demonstrated, difficulties with access to psychiatric care has led to excessive boarding of psychiatric patients in the ED.3,4

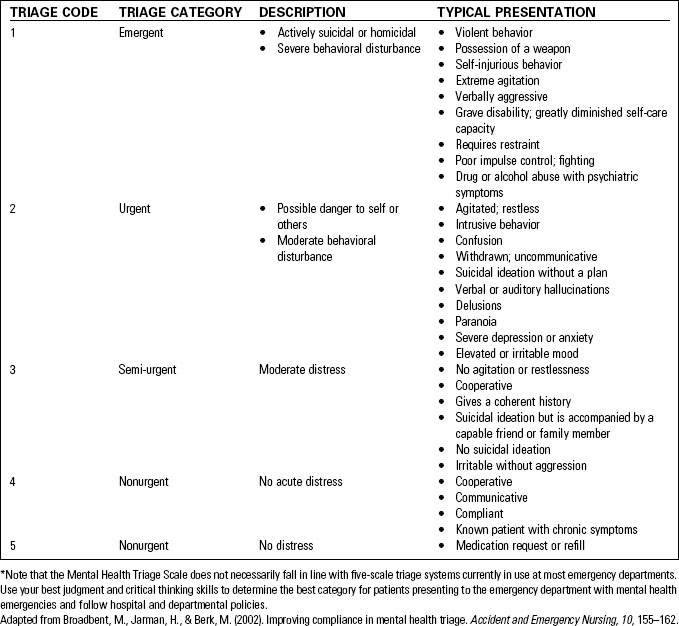

Mental Health Triage

In addition to psychotic conditions, many other mental health emergencies—such as acute anxiety, panic attacks, severe depression, or substance abuse—can cause disordered or dangerous behavior. Evaluation of the patient with a mental health disturbance differs significantly from the typical triage history-taking process. The Emergency Severity Index (ESI) five-level triage categorizations used in most EDs do not fit as well for mental health emergencies as they do for physiologic complaints.5 Based on the parameters listed in Table 48-1, individuals with mental health emergencies can be assigned a triage category.

Mental Health Assessment

Secondary Assessment

General Approach to the Patient

When caring for patients with mental health emergencies the following are useful guidelines:

• Attempt to establish a therapeutic alliance and rapport

• Use direct eye contact (within cultural considerations)

• Let the patient know that there is genuine concern for him or her as a person

• Listen attentively (active listening) but redirect as needed

• Speak clearly and without using jargon

• Encourage patient participation in decision making when possible

• Expect safe behavior and state this clearly

• Anticipate the emotional component (such as anger, crying, or grief)

• Explain procedures and medications to the patient

• Do not be afraid to admit ignorance

• Include the patient’s family and significant other if possible

Mental Health Emergencies Without Psychoses

Table 48-2 shows the classification of mental health emergencies used in this chapter.

TABLE 48-2 CLASSIFICATION OF MENTAL HEALTH EMERGENCIES

| MENTAL HEALTH EMERGENCIES WITHOUT PSYCHOSIS | MENTAL HEALTH EMERGENCIES WITH PSYCHOSIS |

|---|---|

| Acute psychotic reactions Schizophrenia Paranoia Bipolar disorder—mania | |

| Suicide |

Anxiety Disorders

Anxiety is a diffuse, unfocused response that alerts an individual to an impending threat, real or imagined. Fear, on the other hand, is a natural psychological and physiologic reaction to an actual or potential threat.7 Fear is object focused, whereas anxiety involves a faceless, nonspecific threat; no identifiable object can be isolated. Anxiety disorders include panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and phobias (social phobia, agoraphobia, and specific phobias). Anxiety disorders frequently co-occur with depressive disorders or substance abuse. Approximately 40 million American adults aged 18 years and older, or about 18.1% of people in this age group in a given year, have an anxiety disorder.2

Panic Disorder and Acute Anxiety Attacks

Approximately 6 million adults aged 18 years and older, or about 2.7% of people in this age group, have a panic disorder in a given year.2 Onset is usually in early adulthood (median age of onset is 24 years).2 Women are twice as likely to be affected as men.2

Signs and Symptoms

Therapeutic Interventions.

• Provide general emotional support.

• Rule out physiologic causes of symptoms.

• Resolve concerns about safety but avoid false reassurance.

• Identify and treat hyperventilation—encourage slow, regular breathing.

• Encourage the patient to talk.

• Attend to physical symptoms.

• Direct the patient toward reality.

• Consider the use of antianxiety medications.

• Emphasize the importance of mental health treatment on a nonemergency basis.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

Symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) often begin during childhood or adolescence. According to the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), approximately 2.2 million American adults aged 18 years and older, or about 1% of people in this age group, have OCD.2 One third of adults with OCD developed symptoms as children and research indicates that OCD may have familial tendencies. It affects men and women in roughly equal numbers.2,8 Diagnostic criteria for OCD generally involve obsessions and compulsions. Obsessions are recurrent thoughts, images, and impulses that invade the mind, causing intolerable anxiety. These preoccupations make no sense and may be repulsive or revolve around themes of violence and harm. Compulsions are devised to relieve the anxiety and doubt generated by an obsession. The person will be driven to perform specific repetitive, ritualized behaviors calculated to temporarily reduce discomfort. These behaviors can take on a life of their own, imprisoning the individual in a pattern of activities. Common compulsions include the following:

• Excessive ordering and arranging

• Incessant checking and rechecking

• Repetitive counting, touching, and activity rituals

• Excessive slowness in activities such as eating or tooth brushing

• Constant searching for reassurance that the perceived threat has been removed

Persons with OCD are not delusional and are not having hallucinations; they simply cannot control the compulsive responses to their anxiety.8

Post-traumatic Stress Disorder

Patients with PTSD experience emotional, physical, behavioral, and psychological impairment. In PTSD, the “fight or flight” response is changed or damaged. People who have PTSD may feel stressed or frightened when they are no longer in danger.9

It is estimated that approximately 7.7 million American adults aged 18 years and older, or about 3.5% of people in this age group, have PTSD in a given year. It can develop at any age, including during childhood.2 Individuals who have PTSD may be at increased risk for substance abuse, impaired relationships, and suicide.

Signs and Symptoms.

Symptoms of PTSD can be categorized as re-experiencing, avoidance, and hyperarousal. Table 48-3 lists these signs and symptoms.

TABLE 48-3 SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF POST-TRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER

| RE-EXPERIENCING SYMPTOMS | AVOIDANCE SYMPTOMS | HYPERAROUSAL SYMPTOMS |

|---|---|---|

| Flashbacks—reliving the trauma over and over Bad dreams or nightmares | Staying away from places, events, and objects that are reminders of the experience | Easily startled Feeling tense or “on edge” Difficulty sleeping |

| Frightening thoughts | Feeling emotionally numb | Angry outbursts |

| Feeling strong guilt, depression, or worry | ||

| Loss of interest in activities that were previously enjoyed | ||

| Difficulty remembering the traumatic event |

Therapeutic Interventions

• Provide a quiet environment.

• Assess potential for violence.

• Allow patient to verbalize feelings and concerns.

• Identify the traumatic event if appropriate.

• Assist the patient to identify and use a support system.

• Administer antidepressants and anxiolytics as indicated.

• Help patient identify community resources.

Depressive Disorders

Patients with depressive disorders are commonly encountered in emergency care settings. Depressive conditions include major depressive disorder and dysthymic disorder. Depressive disorders have a high prevalence in the general population; major depressive disorder affects approximately 14.8 million American adults, or about 6.7% of the U.S. population aged 18 years and older in a given year.2 Major depressive disorder is more prevalent in women than in men and is the leading cause of disability in the United States for people aged 15 to 44 years.2 Dysthymic disorder, which is a chronic, mild depression, affects approximately 3.3 million American adults (1.5% of the population).2

Normal sadness, grief, and emotional responses to life’s difficulties must be distinguished from a depressive disorder. For the diagnosis of major depressive disorder to be made, depressive symptoms must be present during all or most of the day, every day, for at least 2 weeks.10 A sad or depressed mood is only one of the indictors of clinical depression.

Major Depressive Disorder

Signs and Symptoms

• Feelings of worthlessness, loneliness, helplessness, sadness

• Decreased interest or pleasure in usual activities

• Physical fatigue, loss of energy

• Psychomotor retardation or agitation

• Sleep disturbances (insomnia or hypersomnia)

• Difficulty with decision making

• Weight change (gain or loss) of 5% of body weight in 1 month

• Irritability (especially children and adolescents)

• Decreased ability to concentrate

Therapeutic Interventions

• Provide for the patient’s safety and security.

• Decrease excessive environmental stimuli.

• Avoid forced decision making.

• Encourage expression of feelings.

• Explore sources of emotional support.

• Involve family members, with the patient’s permission.

• Be genuine and empathetic—not judgmental.

• Refer the patient for psychiatric and medication evaluation and psychotherapy.

• Inform the patient and family of the community resources available.