Chapter 108

Medical Malpractice, Risk Management, and Chart Documentation

Origins of Malpractice

The standard of care is defined as a quality of care that would be expected of an ordinary or reasonable physician in the same specialty in a similar circumstance, but not necessarily in the same locality. Trainees such as residents and fellows are not held to the same standard as attending physicians in their respective specialties. Although jurisdictions vary, in general, attendings are indirectly liable for the negligence of residents working under their supervision, and directly liable for inadequate supervision of residents who commit error. A greater than 50% probability (“more likely than not”) defines negligence and the medical standard of care, a lower threshold of proof than the “beyond a reasonable doubt” (< 90% to 95%) standard used in criminal litigation. Furthermore, the defendant physician owes a duty of care to the plaintiff patient. A malpractice allegation contends that the defendant breached that duty by failing to adhere to the standard of care, resulting in injury to the plaintiff.

Why Are Intensivists Sued?

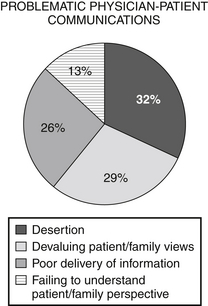

Poor communication between a physician and a patient or patient’s family can frequently lead to litigation (Box 108.1). Most medical malpractice cases do not involve actual negligence. Beckman et al reviewed 45 plaintiffs’ depositions, selected randomly from 67 lawsuits in 1985-1987, all against a large city hospital. The decision to litigate was most often associated with a perceived lack of caring and lack of availability on the part of the practitioner being sued. Additional factors also contribute to the decision by a plaintiff to proceed with a malpractice suit (Figure 108.1).

Medical Malpractice and the Chest Physician

Physicians from medical disciplines that perform the most procedures generally have the most medical malpractice claims. The concept of res ipsa loquitur, “the thing speaks for itself,” means that the plaintiff must prove that an injury could not have occurred absent negligence, could not have been caused by the plaintiff, and was under the defendant’s control. Fulfilling this concept then burdens the defendant to prove that negligence did not occur. An adverse event or outcome following a procedure is enough evidence to convince a jury that negligence has occurred. Five major allegations (Box 108.2) in malpractice suits that generally apply to most physicians, including nonproceduralists, certainly apply to intensivists.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree