Chapter 3 Mass Casualty Incidents

Defining a Disaster

Disasters are commonly categorized by their origin, such as natural, man-made, technological, or human conflict. Many definitions of disaster are found in the literature. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines a disaster as “a serious disruption of the functioning of a community or a society involving widespread human, material, economic, or environmental losses and impacts, which exceeds the ability of the affected community or society to cope using its own resources.”1

The broad scope of the WHO definition includes disasters that cause mass casualties and those that do not involve human injury or illness. A definition of disaster often used by health care systems is “the number of patients presenting, during a given time, that exceed the capacity of an emergency department (ED)/casualty department to provide care and as such, will require additional allocation of human and durable resources from outside the ED.”1 This definition excludes disasters that do not have surviving patients presenting to the emergency department. Many incidences, such as plane crashes, leave few or no survivors. Others, such as technological disasters, often do not include human injury or illness in other settings, but within health care systems these disasters affect patients dependent on technology for survival (those on ventilators or intravenous pump machines). Though most disasters involving technology, such as large power grid failures or computer system failures, do not directly cause injury or illness, these disasters can have serious indirect effects on human lives, typically affecting those most dependent on the technology for survival.

Emergency Management

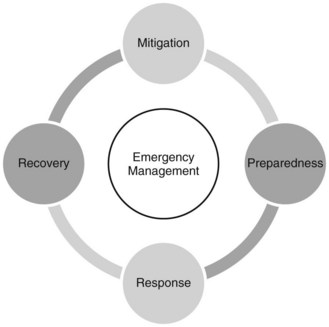

Emergencies can be threats to any health care organization. Since 2008 The Joint Commission has required hospitals to meet the new Emergency Management (EM) standards, which are separate and distinct from the Environment of Care standards.2 These new EM standards are organized around the four phases of EM: mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery (see Fig. 3-1).

TABLE 3-1 FOUR PHASES OF EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT WITH ACTIONS

| Mitigation Take places before and after an emergency occurs | Activities designed to either prevent the occurrence of an emergency or minimize potentially adverse effects of an emergency, including zoning and building code ordinances and enforcement of land use regulations. Action: Buying flood and fire insurance for the home, placing security cameras around the hospital, and installing hurricane shutters are examples of mitigation activities. |

| Preparedness Takes place before an emergency occurs | Activities, programs, and systems that exist prior to an emergency and are used to support and enhance response to an emergency or disaster. Public education, planning, training, and exercising are among the activities conducted under this phase. Action: Evacuation plans and stocking food and water are both examples of preparedness. |

| Response Takes place during an emergency | Activities and programs designed to address the immediate effects of an emergency or disaster, to help reduce casualties and damage, and to speed recovery. Coordination, warning, evacuation, and mass care are examples of response. Action: Seeking shelter from a tornado or turning off gas valves during an earthquake are both response activities. |

| Recovery Takes place after an emergency occurs | Activities involving restoring systems to normal. Recovery actions are taken to assess damage and return vital life support systems to minimum operating standards; long-term recovery may continue for many years. Action: Obtaining financial assistance to help pay for repairs or removing debris are recovery activities. |

Mitigation

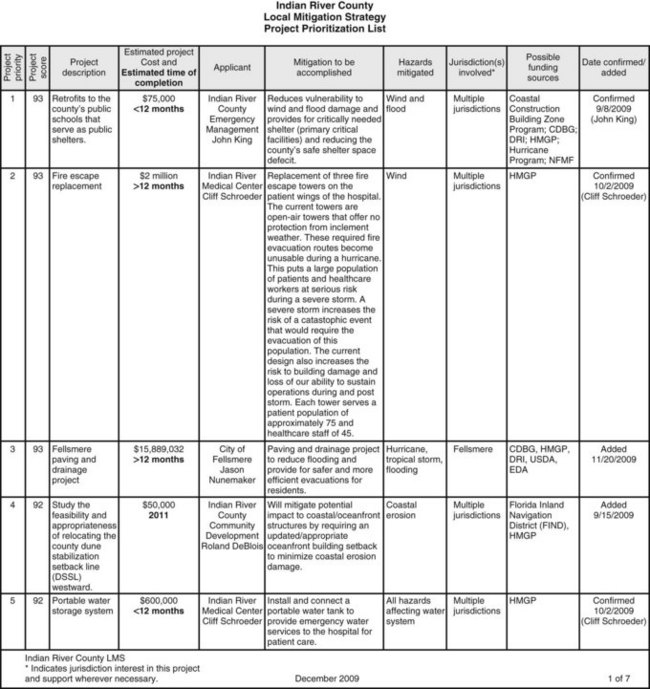

Within hospitals and health care facilities, mitigation implies the steps taken to prevent all possible hazards that may lead to a disaster. The mitigation phase of EM is unique because it focuses on long-term tasks that are effective in reducing or eliminating any risk of a disaster occurring. Obviously not all risks can be eliminated—hurricanes, tornadoes, and other disasters from natural causes are examples. However, when implemented, mitigation strategies minimize the harmful effects of these disasters on the health care facility and its operation. In hurricane-prone areas, for example, hospitals can install shutters to minimize the wind effect on the building. In flood-prone areas, a dam can be built to prevent or minimize the degree of flooding. Another mitigation strategy for hospitals in a flood-prone area is to elevate any critical infrastructure such as energy units (electrical), oxygen farms, or generators. Figure 3-2 is an example of such a mitigation plan.

Fig. 3-2 Example of Indian River County mitigation strategy.

(From Indian River County Florida Board of County Commissioners. [2009, December]. Local mitigation strategy project prioritization list. Retrieved from http://www.ircgov.com/Boards/LMS/2010_Project_List.pdf)

The first step in mitigation is to identify risks. The Joint Commission standards EM.01.01.01 and EM.03.01.01 discuss the need for a hospital to evaluate potential emergencies that could affect demand for the hospital’s services or its ability to provide those services and the effectiveness of its emergency management planning activities aimed at managing those emergencies.2 This includes an annual review of hospital risks, hazards, and potential emergencies as defined in a hazard vulnerability analysis.

Hazard Vulnerability Analysis

A hazard vulnerability analysis (HVA) is a systematic approach to:

• Identify all hazards that may affect an organization and its community

• Assess the risk and probability of hazard occurrence

• Determine the consequence for the organization associated with each hazard

• Analyze the findings to create a prioritized comparison of hazard vulnerabilities

Table 3-2 lists potential threats for HVA consideration.

TABLE 3-2 POTENTIAL THREATS REQUIRING AN EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT PLAN AND RESPONSE

| THREATS FROM NATURAL CAUSES | MAN-MADE THREATS | TERRORIST THREATS |

|---|---|---|

| Pandemic flu | Explosions | Conventional weapons |

| Hurricanes | Hazardous materials | Explosive or incendiary devices |

| Floods | Transportation accidents or incidents | Biological or chemical devices |

| Fire | Assaults, threats, or acts of violence | Radiological exposure devices |

| Tornadoes | Arson | Cyberterrorism |

| Ice storms | Power grid failure | Weapons of mass destruction |

The consequence, or “vulnerability,” is related to both the impact on organizational function and the likely service demands created by the hazard impact. The results of a vulnerability analysis can be used to prioritize mitigation activities and to develop disaster recovery, mitigation, and response plans. Hospital-based HVAs should be conducted with community partners such as local law enforcement, emergency medical services, and fire personnel. Community partners are vital to a true assessment and the basis of mitigation strategies, as many of these partners will be integrated into hospital mitigation and response plans. HVAs should be conducted on an annual basis or more frequently if hospitals, health care facilities, or when populations change (hospital expansion or development of a new infrastructure in the community may affect the demographics of persons seeking health care from that facility).3

Preparedness

• Obtaining information on threats (HVA)

• Planning an organized response to emergencies

• Providing disaster preparedness training for emergencies

• Conducting emergency drills and exercises to test plans and training

• Obtaining and maintaining emergency equipment and facilities

• Establishing intergovernmental coordination arrangements

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree