Chronic pain is a painful condition that lasts >3 months, pain that persists beyond the reasonable time for an injury to heal, or pain that persists 1 month beyond the usual course of an acute disease.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

![]() Chronic pain affects at least 116 million American adults—more than the total affected by heart disease, cancer, and diabetes combined. Pain also costs the nation up to $635 billion each year in medical treatment and lost productivity.

Chronic pain affects at least 116 million American adults—more than the total affected by heart disease, cancer, and diabetes combined. Pain also costs the nation up to $635 billion each year in medical treatment and lost productivity.

![]() Patients who attribute their chronic pain to a specific traumatic event, experience more emotional distress, more life interference, and more severe pain than those with other causes.

Patients who attribute their chronic pain to a specific traumatic event, experience more emotional distress, more life interference, and more severe pain than those with other causes.

![]() Chronic pain may be caused by (1) a chronic pathologic process in the musculoskeletal or vascular system, (2) a chronic pathologic process in one of the organ systems, (3) a prolonged dysfunction in the peripheral or central nervous system, or (4) a psychological or environmental disorder.

Chronic pain may be caused by (1) a chronic pathologic process in the musculoskeletal or vascular system, (2) a chronic pathologic process in one of the organ systems, (3) a prolonged dysfunction in the peripheral or central nervous system, or (4) a psychological or environmental disorder.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

![]() The pathophysiology of chronic pain can be divided into three basic types. Nociceptive pain is associated with ongoing tissue damage. Neuropathic pain is associated with nervous system dysfunction in the absence of ongoing tissue damage. Finally, psychogenic pain has no identifiable cause.

The pathophysiology of chronic pain can be divided into three basic types. Nociceptive pain is associated with ongoing tissue damage. Neuropathic pain is associated with nervous system dysfunction in the absence of ongoing tissue damage. Finally, psychogenic pain has no identifiable cause.

CLINICAL FEATURES

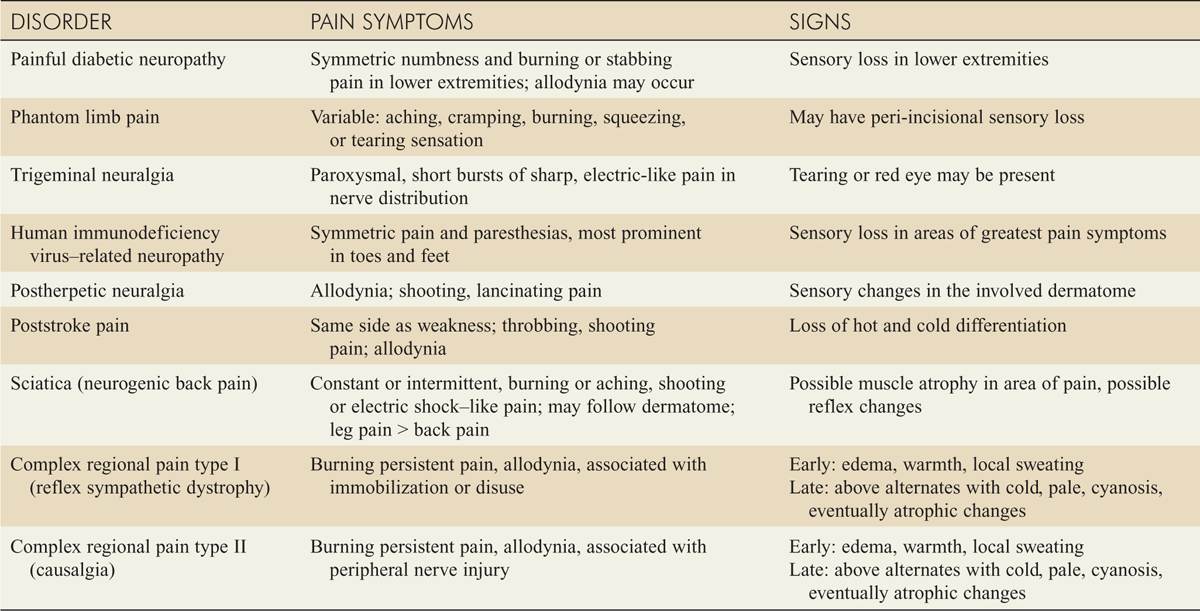

![]() Signs and symptoms of nonneuropathic chronic pain syndromes are summarized in Table 10-1, while signs and symptoms of neuropathic pain syndromes are presented in Table 10-2.

Signs and symptoms of nonneuropathic chronic pain syndromes are summarized in Table 10-1, while signs and symptoms of neuropathic pain syndromes are presented in Table 10-2.

TABLE 10-1 Symptoms and Signs of Nonneuropathic Pain Syndromes

TABLE 10-2 Symptoms and Signs of Neuropathic Pain Syndromes

![]() “Transformed migraine” is a syndrome in which classic migraine headaches change over time and develop into a chronic pain syndrome. One cause of this change is frequent treatment with narcotics.

“Transformed migraine” is a syndrome in which classic migraine headaches change over time and develop into a chronic pain syndrome. One cause of this change is frequent treatment with narcotics.

![]() Fibromyalgia is classified by the American College of Rheumatology as the presence of 11 of 18 specific tender points, nonrestorative sleep, muscle stiffness, and generalized aching pain, with symptoms present longer than 3 months (see www.rheumatology.org).

Fibromyalgia is classified by the American College of Rheumatology as the presence of 11 of 18 specific tender points, nonrestorative sleep, muscle stiffness, and generalized aching pain, with symptoms present longer than 3 months (see www.rheumatology.org).

![]() Risk factors for chronic back pain following an acute episode include male gender, advanced age, evidence of nonorganic disease, leg pain, prolonged initial episode, and significant disability at onset. Passive coping strategies (dependence on medication and others for daily tasks) predict significant disability with chronic back pain.

Risk factors for chronic back pain following an acute episode include male gender, advanced age, evidence of nonorganic disease, leg pain, prolonged initial episode, and significant disability at onset. Passive coping strategies (dependence on medication and others for daily tasks) predict significant disability with chronic back pain.

![]() Patients with complex regional pain type I, also known as reflex sympathetic dystrophy, and complex regional pain type II, also known as causalgia, may be seen in the ED as early as the second week after treatment of an acute injury. These disorders cannot be differentiated from one another on the basis of signs and symptoms. Type I occurs because of prolonged immobilization or disuse, and type II occurs because of a peripheral nerve injury.

Patients with complex regional pain type I, also known as reflex sympathetic dystrophy, and complex regional pain type II, also known as causalgia, may be seen in the ED as early as the second week after treatment of an acute injury. These disorders cannot be differentiated from one another on the basis of signs and symptoms. Type I occurs because of prolonged immobilization or disuse, and type II occurs because of a peripheral nerve injury.

DIAGNOSIS AND DIFFERENTIAL

![]() The most important task of the emergency physician is to distinguish an exacerbation of chronic pain from a presentation that heralds a life- or limb-threatening condition. The history and physical examination (see Tables 10-1 and 10–2) should either confirm the chronic condition or point to the need for further evaluation when unexpected signs or symptoms are elicited.

The most important task of the emergency physician is to distinguish an exacerbation of chronic pain from a presentation that heralds a life- or limb-threatening condition. The history and physical examination (see Tables 10-1 and 10–2) should either confirm the chronic condition or point to the need for further evaluation when unexpected signs or symptoms are elicited.

EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT CARE AND DISPOSITION

![]() The management of chronic pain conditions is listed in Tables 10-3 and 10–4.

The management of chronic pain conditions is listed in Tables 10-3 and 10–4.

![]() The 1990s saw the rise of pain clinics and the use of opioids for chronic pain by specialists and primary care physicians. The increase in prescribed opioids has been accompanied by increases in opioid misuse, abuse, serious injuries, and overdose-related deaths.

The 1990s saw the rise of pain clinics and the use of opioids for chronic pain by specialists and primary care physicians. The increase in prescribed opioids has been accompanied by increases in opioid misuse, abuse, serious injuries, and overdose-related deaths.

![]() Use of opioids for chronic pain increases patient disability, the rates of surgery, and the total cost of health care.

Use of opioids for chronic pain increases patient disability, the rates of surgery, and the total cost of health care.

![]() There are two essential points that affect the use of opioids in the ED on which there is agreement: (a) opioids should only be used in chronic pain if they enhance function at home and at work, and (b) a single practitioner should be the sole prescriber of narcotics or be aware of their administration by others.

There are two essential points that affect the use of opioids in the ED on which there is agreement: (a) opioids should only be used in chronic pain if they enhance function at home and at work, and (b) a single practitioner should be the sole prescriber of narcotics or be aware of their administration by others.

![]() A previous narcotic addiction is a relative contraindication to the use of opioids in chronic pain, because when such patients are treated with opioids, addiction relapse rates approach 50%.

A previous narcotic addiction is a relative contraindication to the use of opioids in chronic pain, because when such patients are treated with opioids, addiction relapse rates approach 50%.

![]() The use of cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) inhibitors has been associated with increased cardiovascular complications and several drugs have been removed from the market.

The use of cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) inhibitors has been associated with increased cardiovascular complications and several drugs have been removed from the market.

![]() The need for long-standing treatment of chronic pain conditions may limit the safety of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Adding a proton pump inhibitor reduces GI complications, and the combination is less expensive than daily use of the COX-2 inhibitors.

The need for long-standing treatment of chronic pain conditions may limit the safety of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Adding a proton pump inhibitor reduces GI complications, and the combination is less expensive than daily use of the COX-2 inhibitors.

![]() An evidence-based review found antidepressants to be effective in chronic low back pain, fibromyalgia, osteoarthritis, and neuropathic pain. A separate meta-analysis found that tricyclic antidepressants were more effective in states in which symptoms were unexplained, such as fibromyalgia.

An evidence-based review found antidepressants to be effective in chronic low back pain, fibromyalgia, osteoarthritis, and neuropathic pain. A separate meta-analysis found that tricyclic antidepressants were more effective in states in which symptoms were unexplained, such as fibromyalgia.

![]() Previous recommendations for bedrest in the treatment of back pain have proven counterproductive. Exercise programs have been found to be helpful in chronic low back pain.

Previous recommendations for bedrest in the treatment of back pain have proven counterproductive. Exercise programs have been found to be helpful in chronic low back pain.

![]() When antidepressants are prescribed in the ED, a follow-up plan should be in place. The most common drug and initial dose is amitriptyline, 10–25 milligrams, 2 hours prior to bedtime.

When antidepressants are prescribed in the ED, a follow-up plan should be in place. The most common drug and initial dose is amitriptyline, 10–25 milligrams, 2 hours prior to bedtime.

![]() A meta-analysis has found calcitonin to be effective in the treatment of complex regional pain, type I (reflex sympathetic dystrophy). Calcitonin can be given at a dose of 100 IU intranasal spray per day.

A meta-analysis has found calcitonin to be effective in the treatment of complex regional pain, type I (reflex sympathetic dystrophy). Calcitonin can be given at a dose of 100 IU intranasal spray per day.

![]() Referral to the appropriate specialist is one of the most productive means to aid in the care of chronic pain patients who present to the ED. Chronic pain clinics have been successful at changing the lives of patients by eliminating opioid use, decreasing pain levels by one-third, and increasing work hours twofold.

Referral to the appropriate specialist is one of the most productive means to aid in the care of chronic pain patients who present to the ED. Chronic pain clinics have been successful at changing the lives of patients by eliminating opioid use, decreasing pain levels by one-third, and increasing work hours twofold.

TABLE 10-3 Management of Nonneuropathic Chronic Pain Syndromes

TABLE 10-4 Typical Features Predicting Difficulties with Opioid Therapy

MANAGEMENT OF PATIENTS WITH DRUG-SEEKING BEHAVIOR

EPIDEMIOLOGY

![]() The Drug Abuse Warning Network has tracked drug-related visits in a sampling of U.S. emergency departments and found that the incidence of visits to the ED involving abuse of narcotic-analgesic combinations rose 85% between 1994 and 2000.

The Drug Abuse Warning Network has tracked drug-related visits in a sampling of U.S. emergency departments and found that the incidence of visits to the ED involving abuse of narcotic-analgesic combinations rose 85% between 1994 and 2000.

![]() A study conducted in Portland found that drug-seeking patients presented to the ED 12.6 times per year, visited 4.1 different hospitals, and used 2.2 different aliases. Patients who were refused narcotics at one facility were successful in obtaining narcotics at another facility 93% of the time and were later successful at obtaining narcotics from the same facility 71% of the time.

A study conducted in Portland found that drug-seeking patients presented to the ED 12.6 times per year, visited 4.1 different hospitals, and used 2.2 different aliases. Patients who were refused narcotics at one facility were successful in obtaining narcotics at another facility 93% of the time and were later successful at obtaining narcotics from the same facility 71% of the time.

CLINICAL FEATURES

![]() Because of the spectrum of drug-seeking patients, the history given may be factual or fraudulent.

Because of the spectrum of drug-seeking patients, the history given may be factual or fraudulent.

![]() Drug seekers may be demanding, intimidating, or flattering.

Drug seekers may be demanding, intimidating, or flattering.

![]() In one ED study, the most common complaints of patients who were seeking drugs were (in decreasing order): back pain, headache, extremity pain, and dental pain.

In one ED study, the most common complaints of patients who were seeking drugs were (in decreasing order): back pain, headache, extremity pain, and dental pain.

![]() Many fraudulent techniques are used, including “lost” prescriptions, “impending” surgery, factitious hematuria with a complaint of kidney stones, self-mutilation, factitious injury, and partner waiting near telephone impersonating a doctor to confirm a diagnosis frequently treated with controlled substances.

Many fraudulent techniques are used, including “lost” prescriptions, “impending” surgery, factitious hematuria with a complaint of kidney stones, self-mutilation, factitious injury, and partner waiting near telephone impersonating a doctor to confirm a diagnosis frequently treated with controlled substances.

TABLE 10-5 Characteristics of Drug-Seeking Behavior

DIAGNOSIS AND DIFFERENTIAL

![]() Drug-seeking behaviors can be divided into two groups: predictive and less predictive (Table 10-5). The behaviors listed under “predictive” are illegal in many states and form a solid basis to refuse narcotics to the patient.

Drug-seeking behaviors can be divided into two groups: predictive and less predictive (Table 10-5). The behaviors listed under “predictive” are illegal in many states and form a solid basis to refuse narcotics to the patient.

EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT CARE AND DISPOSITION

![]() The treatment of drug-seeking behavior is to refuse the controlled substance, consider the need for alternative medication or treatment, and consider referral for drug counseling.

The treatment of drug-seeking behavior is to refuse the controlled substance, consider the need for alternative medication or treatment, and consider referral for drug counseling.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree