INTRODUCTION

This chapter reviews the common acute infectious and structural or anatomic GU disorders. There are five GU emergencies: testicular torsion, Fournier’s gangrene, paraphimosis, priapism, and significant GU trauma (see chapter 265, “Genitourinary Trauma”). Related emergencies include strangulated inguinal hernia (see chapter 84, “Hernias”) and ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm (see chapter 60, “Aneurysmal Disease”), which may present with scrotal pain.

ANATOMY

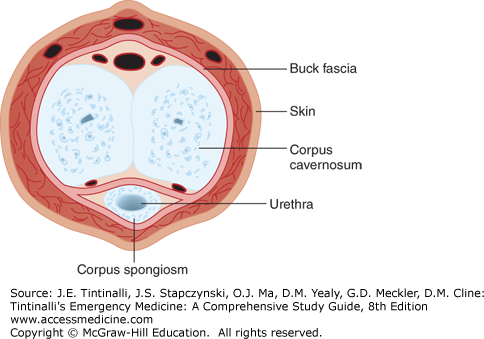

Three cylindrical bodies—the corpus spongiosum, which surrounds the urethra, and the paired corpora cavernosa—form the shaft of the penis (Figure 93-1). The corpora cavernosa are the major erectile bodies, extending distally from the pubic rami and capped by the glans penis. These cylindrical structures are encased in a thick tunic of dense connective tissue, the tunica albuginea. External to the tunica albuginea is Buck’s fascia, which fuses with Colles’ fascia at the level of the urogenital diaphragm. The internal pudendal artery provides the blood supply, which branches to form the deep and superficial penile arteries. Lymphatics drain from the penis into the deep and superficial inguinal nodes.

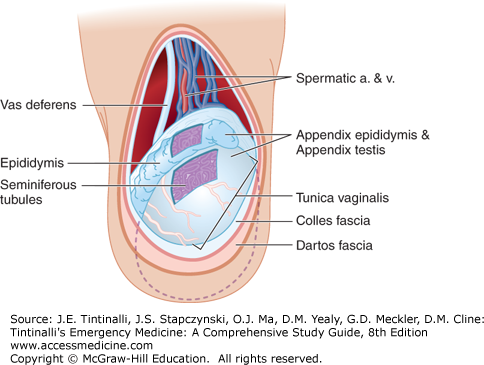

The prepubertal scrotal skin is thin and thickens with subsequent hormonal stimulation during puberty. Immediately beneath the skin are the smooth muscle and elastic tissue layers of Dartos’ fascia, similar to the superficial fatty layer (Camper’s fascia) of the abdominal wall. The deep membranous layer (Scarpa’s fascia) of the abdominal wall extends into the perineum, where it is referred to as Colles’ fascia, and forms part of the scrotal wall (Figure 93-2). The blood supply is derived primarily from branches of the femoral and internal pudendal arteries. Lymphatics from the scrotum drain into the inguinal and femoral nodes.

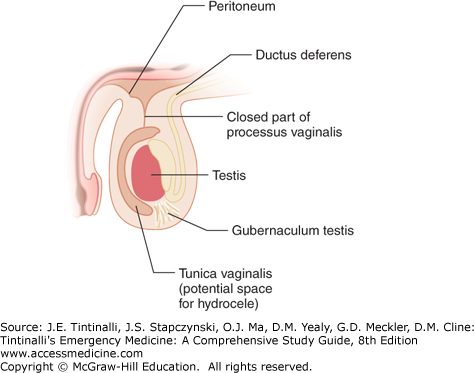

The testes average in size between 4 and 5 cm in length and 3 cm in width and depth, and usually lie in an upright position, with the superior portion tipped slightly forward and outward. Each testis is encased in a thick fibrous tunica albuginea except posterolaterally, where it is in tight apposition with the epididymis. The enveloping tunica vaginalis covers the anterior and lateral aspects of the testes and attaches to the posterior scrotal wall. Superiorly, the testes are suspended from the spermatic cord; inferiorly, the testis is anchored to the scrotum by the scrotal ligament (gubernaculum). Maldevelopment with lack of firm posterior fixation of the tunica vaginalis leaves the testes and epididymis at risk for torsion about the spermatic cord. The posterior (visceral) leaf of the tunica vaginalis is adherent with the tunica albuginea of the anterior testicular surface. A potential space exists between this visceral leaf and the anterior (parietal) tunica vaginalis. Any traumatic or inflammatory event can impede the normal parietal tunica vaginalis from absorbing viscerally secreted fluid, resulting in hydrocele formation anterior to the testes (Figure 93-3). Hematocele results from accumulation of blood in the potential space.

The internal spermatic and external spermatic arteries provide the blood supply, traveling together in the spermatic cord. Venous return is primarily by the internal spermatic, epigastric, internal circumflex, and scrotal veins. The lymphatics drain toward the external, common iliac, and periaortic nodes.

The epididymis is a single, fine, tubular structure approximately 4 to 5 m long compressed into an area of about 5 cm. It serves to promote sperm maturation and motility. Vestigial embryonic structures, the appendix epididymis and the appendix testis, which have no known physiologic function, are often associated with the testes and epididymis. The appendix epididymis is found attached to the head of the epididymis, or globus major. The appendix testis, a pear-shaped structure, is usually situated on the uppermost portion of the testis at the junction of the testis and the globus major of the epididymis, although anatomic variation exists.

The vas deferens is a distinct muscular tube that is easily palpable within the scrotal sac. It extends cephalad in the spermatic cord from the tail of the epididymis (globus minor), traverses the inguinal canal, and crosses medially behind the bladder over the ureters to form the ampullae of the vas, where it joins with the seminal vesicles to form the paired ejaculatory ducts in the prostatic urethra.

The prostate originates from the urogenital sinus at approximately the third month of embryonic life. It is continually enlarging and, in the young male, is often not definable on rectal examination. As a man matures, the prostate may enlarge dramatically, resulting in significant bladder outlet obstruction. The anterior, median, posterior, and lateral lobes define the divisions of the prostate.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The GU examination should be performed with the male patient in both the supine and upright positions in a well-illuminated, warm room if feasible. In uncircumcised males, fully retract the foreskin to inspect the glans, coronal sulcus, and preputial (foreskin) areas for ulceration or lesions. Note the location of the urethral meatus and presence of discharge. Replace the foreskin to its native position following examination to prevent iatrogenic paraphimosis. Carefully palpate the penile shaft for skin or subcutaneous lesions.

Testicular nodularity or firmness should be considered carcinoma until proven otherwise. The epididymis usually lies on the posterolateral aspect of the testis and has a soft, fleshy feel similar to that of the earlobe. Many males experience pain and tenderness with palpation of a normal globus major (head), body, and globus minor (tail) of the epididymis. Males experience some discomfort during palpation of a normal prostate, and a lateral supine position helps prevent an infrequent vasovagal response. The prostate has a heart-shaped contour, with its apex located more distally, abutting the urogenital diaphragm. The consistency of the normal prostate has the same resiliency as the cartilaginous tip of the nose, whereas suspicious carcinogenic areas feel more like the bony prominence of the chin. The posterior lobe is small and thin, allowing palpation of the median raphe that distinguishes the two lateral lobes. A rectal prostate examination cannot assess the anterior or median lobes. The seminal vesicles, lying just superior to the prostate, cannot normally be distinguished unless there is inflammation, induration, or enlargement.

Examination of the inguinal canals for hernias and the scrotal spermatic cords for varicoceles is best done in the upright position, with the patient straining at the designated time. When the patient is upright, it should be determined whether the testes are aligned along a vertical or horizontal axis. Horizontally aligned testes are at greater risk for torsion. Likewise, an elevated, horizontally aligned testis may be the result of torsion.

DISORDERS OF THE SCROTUM

An acute scrotum is defined as acute pain or painful swelling of the scrotum or its contents, accompanied by local signs or general symptoms. Testicular torsion and Fournier’s gangrene are the most time-sensitive diagnoses of the acute scrotum; the first priority in the evaluation of patients with scrotal pain is differentiation these life- or testicular-threatening disorders from other entities.

Insect bites, human bites, and contact dermatitis may cause scrotal edema, or it may be idiopathic in young boys.1 In the setting of hypoalbuminemia, or anasarca from any cause, contiguous scrotal and penile edema may occur. Idiopathic scrotal edema presents as unilateral or bilateral pain with scrotal, perineal, and inguinal swelling and erythema in boys between 3 and 9 years of age. US findings include an easily compressible thickened scrotal wall (mean 11.2 mm), increased peritesticular blood flow, and in some cases, a reactive hydrocele.2,3 Episodes resolve in 1 to 4 days with scrotal elevation, rest, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, although recurrences occur.4 Antibiotics are sometimes used, but are not typically needed unless fever, increased warmth, or purulence is noted.

Management of a scrotal abscess depends on its depth. In the case of a simple hair follicle abscess, the phlegmon is localized to the scrotal wall. A superficial abscess should be differentiated from a deeper abscess involving or originating from infection in one of the primary intrascrotal organs (i.e., testis, epididymis, or bulbous urethra). This distinction is difficult late in the course of the infection when a general scrotal mass may be the only physical finding. US can determine contiguous involvement of an inflammatory mass in the testis or epididymis with the scrotal skin. When in question, a retrograde urethrogram will delineate the integrity of the urethra.

A simple hair follicle scrotal wall abscess is managed by incision and drainage. Frequently, wound care can be simplified by circumferential excision of the entire roof of the abscess. This allows access for wound care and sitz baths and assures healing from the base outward.1 Antibiotics are rarely needed in an immunocompetent male unless there are signs of cellulitis or systemic involvement. Definitive care of deep-seated or complex abscesses require consultation with urology.

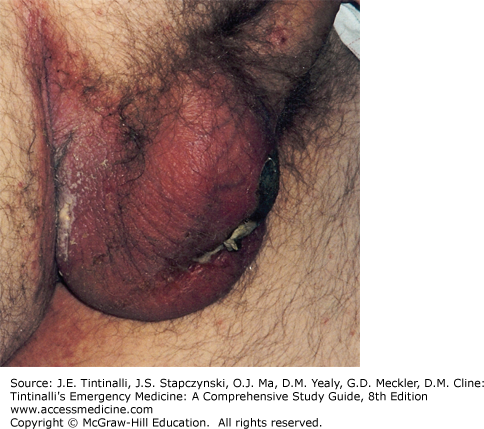

Fournier’s gangrene is a polymicrobial, synergistic, infective necrotizing fasciitis of the perineal, genital, or perianal anatomy. This process typically begins as a benign infection or simple abscess that quickly becomes virulent, especially in an immunocompromised host, and results in microthrombosis of the small subcutaneous vessels, leading to the development of gangrene of the overlying skin. (Figure 93-4).5

Patients with diabetes and alcohol abuse are disproportionately affected with Fournier’s gangrene.6 Mortality rates have varied from 3% to 67%,7 but contemporary estimates range from 20% to 40%.8,9,10,11,12,13 Age over 60 and complications during treatment are the most important predictors of death.12,13

In advanced Fournier’s gangrene, the local signs and symptoms are usually dramatic, with marked pain and swelling. Crepitus and ecchymosis of the inflamed tissues are common features. Prompt recognition of Fournier’s gangrene in its early stages may prevent extensive tissue loss that accompanies delayed diagnosis or treatment. Treat with aggressive fluid resuscitation, gram-positive, gram-negative, and anaerobic antibiotic coverage (see also chapter 151, “Sepsis”). Recommended agents include piperacillin-tazobactam, 3.375 to 4.5 grams IV every 6 hours, or imipenem, 1 gram IV every 24 hours, or meropenem, 500 milligrams to 1 gram IV every 8 hours, plus vancomycin.7,8,9 Urgent urologic consultation is required for wide surgical debridement.7 The addition of clindamycin, 600 to 900 milligrams IV every 8 hours, or metronidazole, 1 gram IV, then 500 milligrams IV every 8 hours, to the antimicrobial regimen may be of benefit.7 Hyperbaric oxygen therapy in the pre- and postoperative setting is a treatment option but does not improve mortality.14 Admission to the intensive care unit postoperatively is typically required.7

DISORDERS OF THE PENIS

Ischemic priapism, paraphimosis, and entrapment injuries are priority diagnoses that, if left untreated, can result in necrosis of the penis.

Balanitis (inflammation of the glans penis), posthitis (inflammation of the foreskin), and balanoposthitis (inflammation of the glans and the foreskin) are primarily caused by inadequate hygiene or external irritation with subsequent colonization with Candida species, Staphylococcus species, Streptococcus species,15 and less commonly, Mycoplasma genialium.16 Infections are frequently mixed flora.15 On examination, when foreskin retraction is attempted, the glans and apposing prepuce appear purulent, excoriated, malodorous, and tender. Balanoposthitis can be the sole presenting sign of diabetes.17 Consider Candida, Gardnerella, and anaerobes as potential causes.15 Treatment consists of cleansing the area with saline, ensuring adequate dryness after cleaning, application of antifungal creams (nystatin or clotrimazole), treatment with an oral azole in severe cases (fluconazole 150 milligrams orally), and circumcision for recurrent cases.15 Soap may increase inflammation during the acute phase, but routine hygiene is essential to prevent reoccurrence. Bacterial infection is suggested by warmth, erythema, and edema of the glans, foreskin, and penile shaft; anaerobic organism is suggested by foul smell.15 If these signs are present, oral clindamycin, 300 milligrams three times per day for 7 days, or metronidazole, 500 milligrams two time per day for 7 days, is recommended.15,18 Cases that persist warrant culture for potential infective causes or biopsy and follow-up with urology.

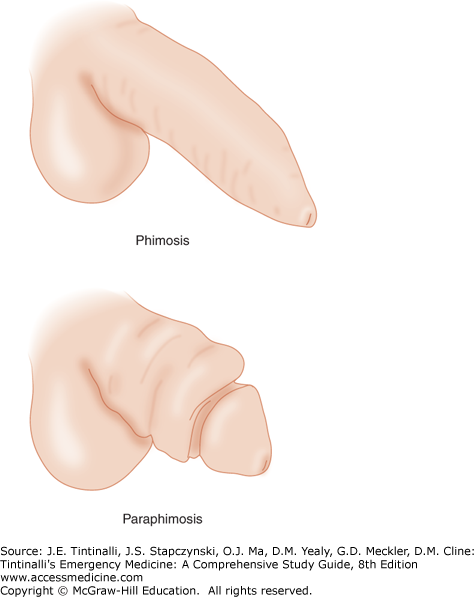

Phimosis is the inability to retract the foreskin proximally and posterior to the glans penis (Figure 93-5). Physiologic phimosis occurs naturally in uncircumcised newborns. By 3 years of age, fewer than 10% of foreskins remain nonretractile, with nearly all becoming retractile by late adolescence. Infection, poor hygiene, and previous preputial injuries with scarring are common causes of pathologic phimosis. Scarring at the tip of the foreskin can occlude the preputial meatus, infrequently causing urinary retention. Hemostatic dilation of the preputial ostium will temporarily relieve the urinary retention. Circumcision is curative. Alternatively, topical steroid treatment (such as betamethasone, 0.05% to 0.10% twice daily) applied from the tip of the foreskin to the glandis corona for 1 to 2 months, along with daily manual preputial retraction, has been shown to be an effective nonsurgical management option for phimosis.19

Paraphimosis, a true urologic emergency, is the inability to reduce the proximal edematous foreskin distally over the glans penis into its natural position (Figure 93-5). The resulting glans edema and venous engorgement can progress to arterial compromise and gangrene.

Paraphimosis can often be reduced by compression of the glans for several minutes to reduce edema and allow for successful reduction of the now smaller glans through the foreskin. Tightly wrapping the glans with a 2-inch elastic bandage for 5 minutes will reduce edema. A local anesthetic block of the penis can help the patient tolerate the pain of compression but also adds fluid to an already swollen penis. The patient may require an anxiolytic before the injection of a “ring” of local anesthetic at the base of the penis. If these methods are unsuccessful, local infiltration of the constricting band with 1% lidocaine without epinephrine followed by superficial dorsal incision of the band will allow foreskin reduction.20 Use of an iris scissor may help prevent damage to underlying tissue. The examining provider should perform this procedure in cases of impaired perfusion to the glans, unless a urologist is immediately available.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree