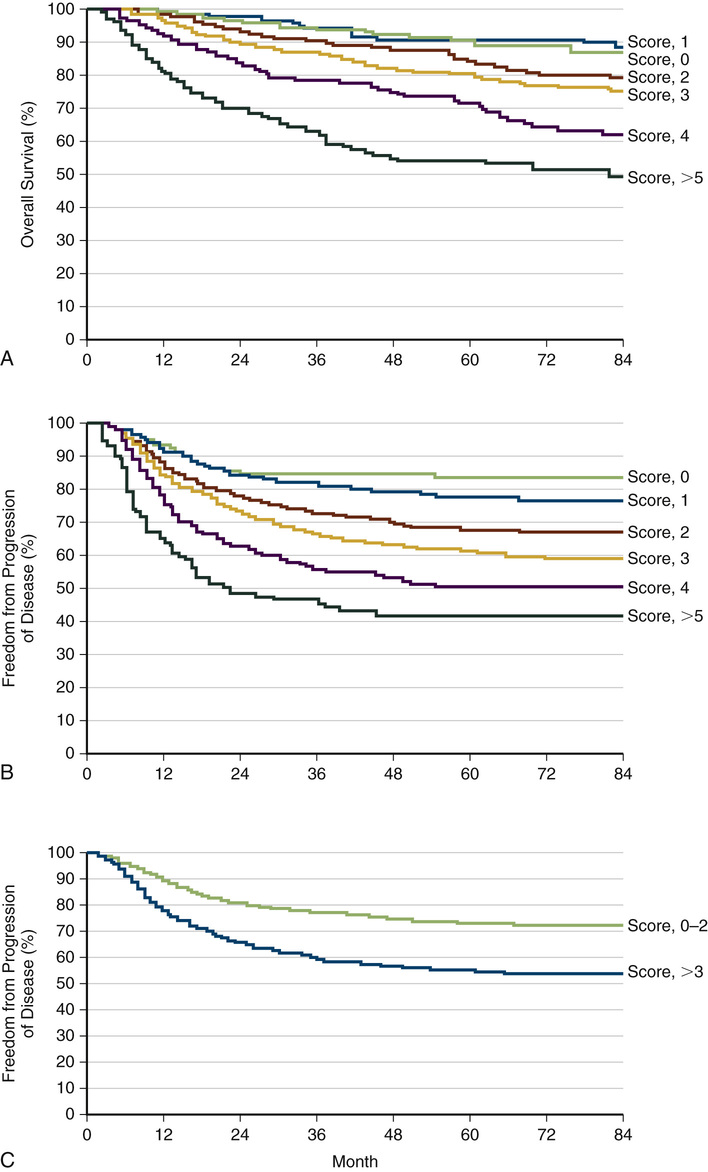

Varghese Mathai Lymphomas are clonal disorders that arise from lymphocytes (B or T cells; rarely, natural killer [NK] cells). They are rare and extremely heterogeneous secondary to numerous histologic subtypes and variable clinical presentations. This heterogeneity has important prognostic implications on whether treatment is administered with curative intent. This focus of this chapter is twofold: (1) to enable an understanding of the diagnosis, staging, and initial evaluation of a lymphoma patient, and (2) to describe how the most common lymphoid malignancies are managed. The estimates from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program for 2014 revealed that non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) was the seventh most common type of cancer. NHL and Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) represented 5% percent of new cancer cases (NHL, 70,800; HL, 9190) and 3.5% of cancer deaths in 2014. The incidence of these disorders has increased approximately twofold over the last 30 years, with a slight male predominance.1 The cause is unclear, but the increase is most significant in older patients with aggressive lymphoma. Many associate the increase in NHL with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), but with the widespread use of antiretroviral therapies the incidence of lymphoma has begun to decline. The many different forms of lymphoma have varied causes. The possible causes and associations with at least some forms of NHL include the following: • Epstein-Barr virus—associated with Burkitt lymphoma, HL, follicular dendritic cell sarcoma, extranodal NK–T-cell lymphoma2 • Human T-cell leukemia virus—associated with adult T-cell lymphoma • Helicobacter pylori—associated with gastric lymphoma • Hepatitis C virus—associated with splenic marginal zone lymphoma, lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL)3 • Chemicals: polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) diphenylhydantoin, dioxin, and phenoxy herbicides5 • Medical treatments, including radiation therapy and chemotherapy • Genetic diseases, including Klinefelter syndrome, Chédiak-Higashi syndrome, ataxia-telangiectasia syndrome6 • Autoimmune diseases: Sjögren syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus The clinical presentation of HL and NHL varies and is dependent on the type of lymphoma and the area of involvement. Many patients have lymphadenopathy. In general, lymph nodes persisting for more than 4 weeks and lymph nodes larger than normal (up to 1.5 cm) will require intervention. In aggressive and highly aggressive NHLs, the lymphadenopathy increases quickly. Node size can wax and wane in more indolent lymphomas. “B” symptoms are often present in disseminated disease. These include fever higher than 38° C, drenching night sweats, and unintentional weight loss of more than 10% of body weight. See specific discussion later. The initial evaluation includes the patient’s history and a complete physical examination (including assessment of functional status using standardized scales such as the ECOG/Zubrod scale or the Karnofsky performance scale, both available online). A complete blood count (CBC), electrolytes, liver and renal function studies, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), infectious disease panel (hepatitis B and C, HIV), and examination of the peripheral smear for the presence of atypical cells are initial diagnostics. Further diagnostics include a bone marrow biopsy and aspiration, positron emission tomography (PET), and computed tomography (CT) scan with intravenous and oral contrast. After initial evaluation, proper histologic diagnosis and precise classification of the lymphoid neoplasm are the starting points for proper management. To allow for full assessment, an excisional biopsy is preferred when possible (versus core biopsy) to make the initial diagnosis of lymphoma. If a patient has already been treated for NHL or HL and a relapse is suspected, then core biopsy will suffice. The demonstration of monoclonality in biopsied tissue is diagnostic for lymphoma. The absence of monoclonality should make the underlying diagnosis questionable, and a repeat biopsy will likely be necessary. Several classification systems have existed over the decades and continue to evolve. The latest, most comprehensive classification is the World Health Organization (WHO) classification developed in 2008.7 The WHO classification is broken down by cell of origin (B, T, or NK) and by cell maturity. The WHO modification of the Revised European-American Lymphoma (REAL) classification recognizes three major categories of lymphoid malignancies based on morphology and cell lineage: B-cell neoplasms, T-cell/NK-cell neoplasms, and Hodgkin lymphoma (HL). Both lymphomas and lymphoid leukemias are included in this classification because both solid and circulating phases are present in many lymphoid neoplasms, and distinction between them is artificial. Within the B-cell and T-cell categories, two subdivisions are recognized: precursor neoplasms, which correspond to the earliest stages of differentiation, and more mature differentiated neoplasms.8 The Ann Arbor staging classification, modified at Cotswold’s meeting in 1989 and initially used for HL, is also used for NHL (Table 240-1). TABLE 240-1 Ann Arbor Staging System for Lymphoma To complete staging, a bone marrow biopsy is performed. The bone marrow aspirate is less important, because it does not preserve morphology and may miss lymphoma. Bilateral biopsies increase the yield but change the stage in only a small number of patients. Lumbar puncture should be examined in highly aggressive lymphomas (Burkitt and lymphoblastic) and with aggressive lymphomas with multiple extranodal sites, paraspinal disease, or testicular or paranasal sinus involvement. HL, formerly called Hodgkin disease, arises from germinal center or post–germinal center B cells. HL has a unique cellular composition, containing a minority of neoplastic cells (Reed-Sternberg cells and their variants) in an inflammatory background9 containing a variable number of small lymphocytes, eosinophils, neutrophils, histiocytes, plasma cells, fibroblasts, and collagen fibers. Morphologic features also determine the various subtypes of classical HL. It is separated from the other B cell lymphomas based on its unique clinicopathologic features, and can be divided into two major subgroups based on the appearance and immunophenotype of the tumor cells: The tumor cells in the classical HL group are also derived from germinal center B cells, but typically fail to express many of the genes and gene products that define normal germinal center B cells. Based on differences in the appearance of the tumor cells and the composition of the reactive background, classical HL is further divided into the following subtypes: The tumor cells in this subtype retain the immunophenotypic features of germinal center B cells. Patients usually have painless adenopathy localized to the neck. The mediastinum is involved in the majority of patients (approximately two thirds), occasionally with large mediastinal masses. B symptoms are present in 20% to 25% of patients. Pruritus is common but is not a B symptom. On rare occasions, patients may experience pain in involved lymph nodes on ingesting alcohol—thought to be a result of alcohol-induced degranulation of eosinophils. The diagnosis of HL is made by the microscopic evaluation of involved tissue, usually obtained from a lymph node biopsy. Excisional biopsies are preferred, and large core needle biopsies may be adequate in select cases, but fine-needle aspiration (FNA) alone often does not provide enough tissue or information on the structural composition of the lymph node to enable an accurate diagnosis. Evaluation of the biopsy material should include both routine light microscopy and analysis of the immunophenotype with immunohistochemistry. Lymphadenopathy may be a primary or secondary sign of numerous disorders including infectious diseases, immunologic disorders, and malignancies (see Chapter 226). A patient with lymphadenopathy that is unexplained and persistent for 1 month should be referred for biopsy to rule out malignant disease. Predicting the outcome is important to avoid overtreating patients with Hodgkin lymphoma and to identify others in whom standard treatment is likely to fail. Prognosticating outcome also helps patients and providers make often difficult treatment decisions. The Hasenclever Index for HL is commonly used.10 Seven factors with similar independent prognostic effects were selected. The prognostic score was then defined as the number of adverse prognostic factors present at diagnosis. The prognostic score was used to predict rates of freedom from progression of disease (Fig. 240-1A) and overall survival (Fig. 240-1B). Figure 240-1 also presents freedom from progression of disease according to whether the prognostic score was 0 to 2, 3, or higher. A score of 1 is given for each of the following risk factors present at diagnosis: • Hemoglobin (Hb) below 10.5 g/dL • White blood cell (WBC) count higher than 15 × 109 per liter of blood • Lymphopenia—fewer than 0.6 × 109 lymphocytes per liter of blood

Lymphomas

Overview of Lymphomas

Epidemiology

Etiology and Risk Factors

Clinical Presentation

Initial Evaluation

Making the Diagnosis

Classification

Staging

Stage*

Substage†

Definition

I

I

Single node region

IE

Single extralymphatic site or involvement by direct extension

II

II

Two or more node regions on same side of diaphragm

IIE

Single node region plus single localized extranodal site

IIS

Spleen

IIE+S

Extralymphatic site plus spleen

III

III

Involvement on both sides of diaphragm

IV

IV

Diffuse extralymphatic involvement

Hodgkin Lymphoma

Pathophysiology

Classical Hodgkin Lymphoma

Nodular Lymphocyte-Predominant Hodgkin Lymphoma

Clinical Presentation

Diagnostics

Differential Diagnosis

Prognosis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Lymphomas

Chapter 240