LYMPHADENOPATHY

KIYETTA H. ALADE, MD, RDMS, FAAP AND BETH M. D’AMICO, MD

Lymphadenopathy, defined as an enlargement of lymph nodes, is a frequent presenting sign in children. Most illnesses causing lymphadenopathy are common viral or bacterial infections that improve spontaneously or with an appropriate course of antimicrobial therapy. However, some serious illnesses, including malignancies, can present first as lymphadenopathy. Thus, a focused history, thorough physical examination, and knowledge of various causes of adenopathy are important in formulating an appropriate differential diagnosis.

MECHANISM OF LYMPHADENOPATHY

Enlargement of lymph nodes can be due to physiologic or pathologic causes. Most commonly, when lymph nodes perform their normal function, antigenic stimulation causes proliferation of lymphocytes, and nodes increase in size. This response is particularly active in children, who are frequently exposed to new antigens, thus accounting for the common observation of lymphadenopathy associated with pediatric infections. A second cause of lymph node enlargement occurs when bacteria or other pathogens that are present in lymphatic fluid stimulate an influx of inflammatory cells, local cytokine release, and symptoms of lymphadenitis. These include enlargement of the node, erythema, edema, and tenderness. A third cause of adenopathy is neoplastic disease, where malignant cells originate in or migrate to lymph nodes, infiltrating the node and causing enlargement. Last, in rare cases genetic storage diseases may lead to deposition of foreign material within the node.

A number of studies have described the presence of palpable lymph nodes in healthy infants and children. A seminal study of well infants and children up to 6 years of age reported more than half of the children had palpable nodes, most commonly in the cervical, occipital, and submandibular region. It is commonly accepted that lymph nodes in the cervical and axillary regions up to 1 cm in diameter, nodes in the inguinal region up to 1.5 cm in diameter, and nodes in the epitrochlear region up to 0.5 cm in diameter are considered normal in children.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

As the differential diagnosis of lymphadenopathy is extensive, it is helpful to distinguish localized from generalized lymphadenopathy, and an acute from chronic time course. Localized adenopathy includes lymphadenopathy in a single region, and generally occurs in response to a focal infectious process. Generalized lymphadenopathy is defined as enlargement of more than two noncontiguous lymph node regions. The most common causes of generalized adenopathy are systemic infections, autoimmune diseases, and neoplastic processes. Lymphadenopathy of greater than 3 weeks duration is considered chronic.

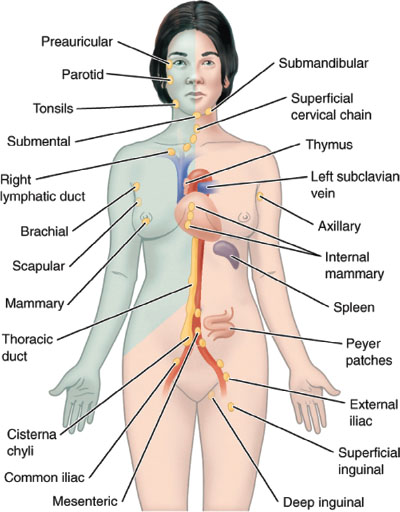

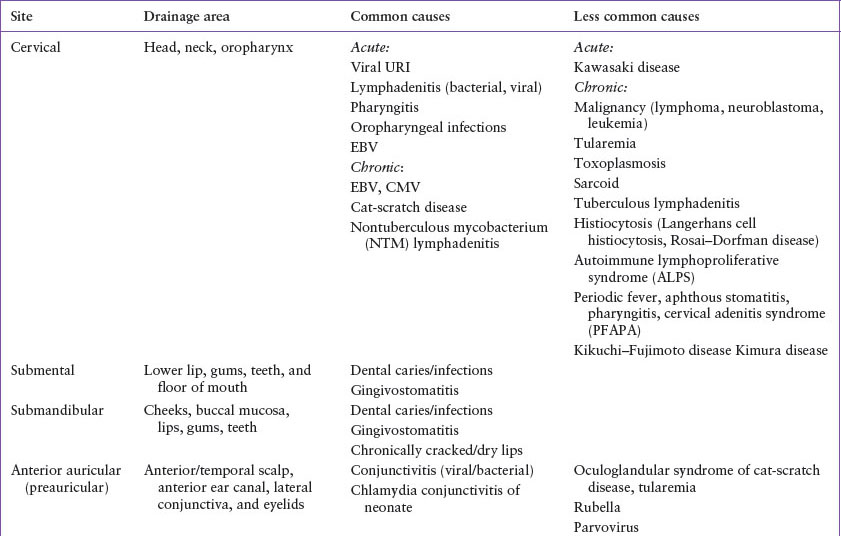

The clinician caring for a child with lymphadenopathy will benefit from knowledge of the anatomic distribution of nodes in the area and their drainage patterns as described in Figures 42.1 and 42.2, as well as Table 42.1. The location of lymphadenopathy is often suggestive of a possible cause.

CAUSES OF LYMPHADENOPATHY BY REGION

Cervical

Enlargement of cervical lymph nodes is a common presenting sign in a variety of pediatric illnesses. In order to narrow the differential diagnosis, it is helpful to identify the time course of swelling (acute or chronic); history or presence of localized infections; occurrence of systemic symptoms; and specific location, symmetry, and characteristics of enlarged nodes. Cervical anatomy is complex, however nodes in the region can be classified generally as either superficial or deep. Superficial cervical nodes, palpated readily along the anterior and posterior borders of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, drain the shallow structures of the head and neck—particularly the oropharynx, external ear, and parotid. In contrast, deep cervical nodes, both superior and inferior, receive lymphatic drainage from a wider area of underlying structures of the head and neck, including the nasopharynx, tonsils and adenoids, larynx, and trachea. While there are numerous infectious and noninfectious causes of acute and chronic cervical lymphadenopathy, the most common etiologies in children are infectious (refer Chapter 102 Infectious Disease Emergencies).

By far, the most common cause of acute cervical adenopathy in children is reactive adenopathy associated with a viral upper respiratory tract infection. Superficial nodes are generally symmetrically enlarged, mobile, and minimally tender. Reactive adenopathy may persist for 2 to 3 weeks beyond the resolution of a viral illness. However, there should be no progression in the size or the extent of the adenopathy after resolution of symptoms of the virus.

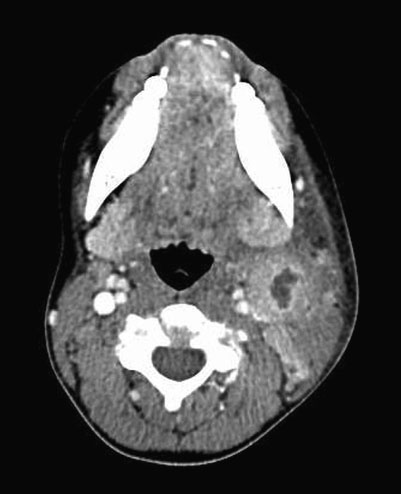

Another common infectious cause of cervical lymph node enlargement, particularly in preschool-aged children, is lymphadenitis. Lymphadenitis occurs when an enlarged node becomes inflamed and tender over the course of a few days, as the result of a viral or bacterial infection. Viral adenitis is often associated with fever, conjunctivitis, pharyngitis, or other symptoms of an upper respiratory tract infection and causes acute bilateral swelling. Common causes are rhinovirus, adenovirus, enterovirus, influenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus, Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), and cytomegalovirus (CMV). Less commonly, herpes simplex, human herpes virus type 6 (roseola), or measles, mumps, or rubella are causative agents. In contrast, bacterial adenitis typically is unilateral and presents with the rapid onset of a firm, tender, and warm lymph node over 1 to 3 days. The overlying soft tissue becomes edematous and erythematous. Fever often accompanies the infection. If left untreated, the node may become suppurative, which is detectable on examination as fluctuance. Acute bacterial adenitis is most often caused by group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus or Staphylococcus aureus (including methicillin-resistant S. aureus [MRSA]). Prompt initiation of oral antimicrobial therapy that empirically covers MRSA can prevent progression to a suppurative infection. However, patients who have failed to improve with oral antimicrobial therapy or those who present with signs of toxicity require parenteral therapy. Drainage of the suppurative nodes is sometimes required, even in appropriately treated cases (Figs. 42.3 and 42.4).

FIGURE 42.1 Lymph nodes of the head and neck. (From Mancuso AA. Head and neck radiology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2010.)

FIGURE 42.2 Lymph nodes of the body. (From Anderson MK. Foundations of athletic training. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2012.)

A third commonly encountered cause of cervical adenopathy in children and adolescents is infectious mononucleosis caused by EBV, a herpes virus. EBV typically causes bilateral anterior and posterior cervical lymph node swelling that is tender to palpation. Nodes may be large and usually peak in size over the first week of illness, gradually subsiding over the next few weeks. The classic presentation of mononucleosis is a prodrome of malaise, headache, and elevated temperature prior to the development of an exudative pharyngitis, tender cervical adenopathy, and fever. Splenomegaly, abdominal pain, and anorexia may be present. Facial edema can accompany significant cervical adenopathy, presumably reflecting obstructed lymphatic drainage. Younger children with EBV infection may present less typically, with fever alone, symptoms of an upper respiratory infection, or abdominal complaints. Diagnosis of infectious mononucleosis can be made in adolescents with the detection of a positive heterophile–agglutinating antibody (e.g., monospot), however, the test may be falsely negative early in the disease course or in young children. Antibody titers directed to specific EBV antigens may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis. In addition, a complete blood count with differential (CBC/d) often shows a lymphocytosis with a large proportion of atypical lymphocytes.

In contrast to the acute cervical adenopathy seen with reactive lymphadenopathy, lymphadenitis, and infectious mononucleosis, there are a number of infectious agents that cause a more indolent course of cervical lymph node swelling. In children, the most common infections causing a subacute or chronic cervical adenopathy include Bartonella henselae, nontuberculous strains of mycobacterium, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Cat-scratch disease is a lymphocutaneous syndrome that follows inoculation of B. henselae through broken skin or mucous membranes, usually caused by contact with a kitten. The primary skin lesion develops within 10 days, and is a small (2 to 5 mm) erythematous papule. After several weeks, lymphadenopathy develops in a site proximal to the lesion. Most often, the cervical or axillary nodes are involved. Nodes are single, large, and tender to palpation. Fever is present in approximately one-third of children. This condition spontaneously resolves within 1 to 3 months, though treatment with azithromycin will result in rapid resolution of lymph node swelling. The indirect immunofluorescent antibody (IFA) assay for detection of serum antibodies to antigens of Bartonella species is used for diagnosis of cat-scratch disease.

Another infectious cause of chronic cervical lymph node swelling is nontuberculous mycobacterium (NTM), also referred to as atypical mycobacterium. NTM is a group of acid-fast bacteria that are found in environmental sources such as soil and water, including the biofilm of home aquariums. Cervical lymphadenitis is the most common manifestation of NTM disease in childhood. Children younger than 5 years are affected. Lymph node involvement is generally unilateral, in the superficial cervical or submandibular region, and rarely larger than 3 to 4 cm. The node is nontender, and enlarges in size slowly over several weeks. Overlying skin may turn a deep purple and gradually thin, developing a paper-like appearance (Fig. 42.5). Without intervention, these nodes may suppurate and adhere to overlying skin, resulting in a chronic draining sinus. Infected children appear well, without systemic symptoms, and may have a history of being treated unsuccessfully with antibiotics aimed at pathogens of typical bacterial adenitis (group A Streptococcus or S. aureus). A clear history of exposure to NTM is the exception rather than the rule. Formal diagnosis is made by culture. Treatment generally involves surgical excision of the node, though antimicrobial therapy may play a role for some patients in addition to or as an alternative to excision.

M. tuberculosis is a rare cause of cervical lymphadenitis in children in the United States, but remains a significant pathogen in other parts of the world. Children with tuberculosis may be of any age. Cervical node enlargement occurs with lymphatic extension from the paratracheal nodes to the cervical and submandibular regions. In addition, supraclavicular node enlargement can be seen as the result of drainage from the apical lung pleura and upper lung fields. The most common presentation is an isolated enlarged node that is nontender, though with progression the node will become fixed and matted, adhering to overlying skin. In children with suspected tuberculous lymphadenitis, it is important to elicit any history of family members or close contacts with a diagnosis of tuberculosis, symptoms of active disease, or risk factors for acquisition (travel, homelessness, incarceration, human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] infection). Diagnosis is made by a combination of skin testing, chest radiograph, and if possible, culture data from the involved node. In addition, newly available serum interferon-γ–release assays (QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube test or T-SPOT.TB test) detect interferon-γ generated by T cells in response to antigens found in M. tuberculosis and are available to aid in diagnosis. Treatment of cervical lymphadenitis consists of antimycobacterial therapy, and should follow established recommendations, such as those from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) (see Chapter 102 Infectious Disease Emergencies).

TABLE 42.1

CAUSES OF REGIONAL LYMPHADENOPATHY

FIGURE 42.3 Child with lymphadenitis that progressed to lymph node abscess.

FIGURE 42.4 Computed tomography (CT) image of lymph node abscess.

FIGURE 42.5 Child with nontuberculous mycobacterium (NTM) lymphadenitis.

There are several rare infectious causes of cervical lymphadenopathy that may be encountered in the pediatric emergency department. Tularemia, caused by infection with Francisella tularensis, occurs predominantly in the South Central United States (Arkansas, Oklahoma, Missouri, and Kansas). It occurs after contact with infected animals (rabbits, hamsters) or via tick or deerfly bites. The most common presentation in children is a febrile illness with tender cervical or occipital adenopathy that may become chronic. An associated papular or ulcerative lesion may be noted on the skin at the site of animal contact or insect bite. Diagnosis is made by detecting serum antibodies to F. tularensis and antimicrobial therapy with doxycycline or a fluoroquinolone is appropriate for mild illness. Toxoplasmosis, a parasitic infection caused by Toxoplasma gondii,

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree