Chapter 60

Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding and Colitis

Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding (LGIB)

History and Causes

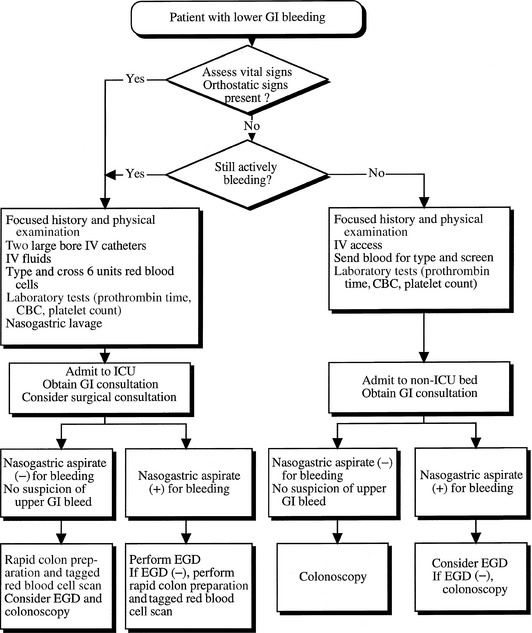

Initial assessment of patients with all GIB should begin with the measurement of vital signs including heart rate and blood pressure (Figure 60.1). Concomitantly with resuscitation, a directed history and a focused physical examination relevant to LGIB should be performed.

The diverse causes of acute LGIB (Table 60.1) can be broadly divided among anatomic, vascular, inflammatory, and neoplastic etiologies. In patients younger than 50 years of age, hemorrhoids are the most common cause, whereas in older patients, diverticulosis and angiodysplasia (arteriovenous malformations) are most frequent. Rectal pain may indicate an anal fissure or hemorrhoids. Abdominal pain may indicate inflammatory bowel disease, ischemia of small or large bowel, or infectious colitis. Painless LGIB, especially in an elderly patient, should increase suspicion of diverticulosis or angiodysplasia. Pain exacerbated with meals can suggest chronic mesenteric ischemia, whereas pain exacerbated by defecation suggests an anal fissure.

TABLE 60.1

Potential Sources for Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding (LGIB)

Massive upper gastrointestinal bleeding

Small intestine sources distal to the ligament of Treitz

—Arteriovenous malformation

—Diverticula

—Inflammatory bowel disease

—Meckel’s diverticulum

—Neoplasm

—Vasculoenteric fistula (postsurgical)

Large intestine sources

—Arteriovenous malformation

—Colitis (infectious or radiation induced)

—Colonic varices (idiopathic or due to portal hypertension)

—Diverticulosis

—Endometriosis

—Hemorrhoids

—Inflammatory bowel disease

—Intussusception with mucosal compromise

—Ischemia

—Neoplasm

—Solitary rectal ulcer

—Vasculitis

The characteristics and color of the patient’s stool in acute LGIB also provide clues about the site of bleeding. Blood from the left side of the colon is typically bright red, whereas blood from the right colon is darker and mixed with stool. Blood on the outside of well-formed stool likely represents an anal canal or rectosigmoid lesion such as hemorrhoids or fissures. A change in bowel habits or stool caliber suggests neoplastic causes. If the patient has bloody diarrhea, consider inflammatory bowel disease or infectious colitis. Although hematochezia, the passage of bright red blood or blood clots per rectum, usually indicates an LGIB source, patients with massive UGIB may also present with hematochezia due to rapid transit of blood through the colon. Hematochezia, in combination with hemodynamic instability, should always raise the possibility of a UGIB. Similarly, LGIB from the distal small bowel or proximal colon can present as melena, or black, tarry stools, a finding typically associated with UGIB and thus an absolute diagnosis of the exact site or etiology of bleeding cannot be made based on the color and characteristics of stool.

Management

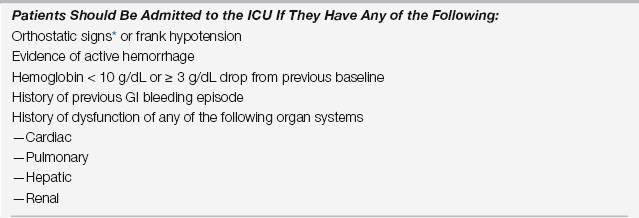

Patients with LGIB should be admitted to the ICU if they meet appropriate clinical criteria of severity or concomitant disease (Table 60.2). Appropriate resuscitation efforts should be initiated, including large bore intravenous line placements, isotonic intravenous fluid infusions, and red blood cell transfusions. The target hemoglobin level depends on the patient’s age and comorbid conditions such as coronary artery disease, emphysema, and chronic kidney disease. For an elderly patient with significant comorbidities, the hemoglobin level should be maintained at 10 g/dL. If a patient has a coagulopathy (International Normalized Ratio [INR] > 1.5) or thrombocytopenia (platelets < 50,000/μL), these should be quickly addressed with transfusions of fresh frozen plasma and platelets, respectively. Vitamin K should be given to patients on warfarin in the setting of active GIB. Early in the management of these patients, a nasogastric lavage should be attempted at bedside to evaluate for a possible UGIB. An upper endoscopy should be considered in patients when a UGIB cannot be definitively excluded based on nasogastric lavage or other clinical information. This is particularly important in patients with hematochezia and hemodynamic instability. The surgical and interventional radiology services should be consulted if the patient has massive bleeding (requiring more than 6 units of blood) or develops signs of an acute surgical abdomen.

TABLE 60.2

Criteria for Admission to the Intensive Care Unit with Acute Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding (LGIB)

ICU, intensive care unit; GI, gastrointestinal.

∗Orthostatic signs are seen when a change in position from supine to erect causes two or more of the following: (1) pulse increase of 20 beats per minute, (2) systolic blood pressure drop ≥ 20 mm Hg, and (3) diastolic blood pressure drop ≥ 10 mm Hg.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Radionuclide Imaging

The major disadvantage of radionuclide scans is erroneous localization of the site of bleeding, which can occur in up to 25% of cases. In addition, these tests are purely diagnostic and do not have the potential for therapeutic intervention. Radionuclide imaging is most helpful in assessing if patients are bleeding vigorously enough to permit visualization of the site by angiography.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree