Chapter 28

Care of the Maternal-Fetal Unit

Maternal Physiologic Changes in Pregnancy

Hemodynamic Changes

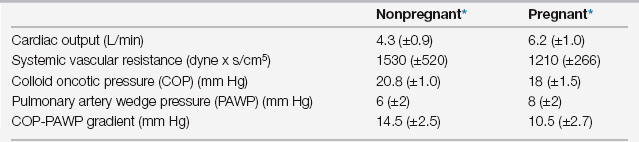

Blood pressure normally decreases during pregnancy secondary to decreased peripheral vascular resistance, an effect of circulating progesterone. The lowest values are seen at 24 to 28 weeks of gestation. Mean systolic blood pressure measures 5 to 10 mm Hg below baseline, whereas diastolic blood pressure falls slightly more, 10 to 15 mm Hg. Mean maternal heart rate increases at the beginning of the third trimester. Cardiac output is increased by 10 weeks of gestation secondary to increased stroke volume and later, in the third trimester, because of an increased heart rate (+15%). In large part, other changes in hemodynamic parameters result from the increased plasma volume associated with pregnancy (Table 28.1).

TABLE 28.1

Hemodynamic Changes Associated with Late Pregnancy

From Clark SL, Cotton DB, Lee W, et al: Central hemodynamic assessment of normal term pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 161:1439-1442, 1989.

Postpartum Hemodynamic Fluctuations

Maternal blood loss from vaginal delivery of a singleton gestation averages ~500 mL. It can be two times that for a cesarean delivery. In the postpartum period, the mother mobilizes extracellular fluid, resulting in a postpartum diuresis equivalent to approximately 3 kg of weight loss. Despite the blood loss and diuresis, stroke volume and cardiac output remain elevated because of increased venous return. The clinical significance of these changes is manifested in a subclass of preeclamptic patients (see Chapter 72) as follows: (1) before delivery they have generalized vasospasm and intravascular volume depletion, (2) postpartum they mobilize their extracellular fluid as expected, (3) they often fail to diurese secondary to restricted renal blood flow, and (4) this places them at high risk for pulmonary or cerebral edema.

Respiratory Changes

Alterations in maternal lung volumes, respiratory mechanics, and arterial blood gas values precede elevation of the diaphragm because of the gravid uterus. Respiratory rate does not change during pregnancy, but tidal volume expands by 30% to 40%. This results in an increased minute ventilation beginning in the first trimester. Progesterone acting on the central respiratory center modulates these changes. Although gravid women frequently report a mild pregnancy-associated dyspnea, their forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) is not decreased. Arterial pH remains at 7.40 during pregnancy, whereas Pao2 is normally elevated at 104 to 108 mm Hg (as a result of chronic hypocapnia via the alveolar gas equation [Equation 12 in Box 1.1 in Chapter 1]), and Paco2 is normally decreased at 27 to 32 mm Hg (secondary to the increased minute ventilation and increased alveolar ventilation [Box 1.1 in Chapter 1]). Increased renal excretion of bicarbonate (normal serum levels in pregnancy are 18 to 21 mEq/L) compensates for decreased Paco2 and maintains the neutral pH. The lower maternal Paco2 facilitates fetal-maternal CO2 diffusion.

Effects of Common Intensive Care Unit Interventions on the Maternal-Fetal Unit

Drug Therapy

Most drugs used in critical care have not been studied extensively in the pregnant population so that little is known regarding their adverse effects on the human fetus. Although the potential risks on the fetus must be considered, as a general rule, the need to treat critical illness to restore maternal well-being should far outweigh these considerations. All drugs are assigned to categories representing degrees of fetal risk (Table 28.2). These categories are indicated in parentheses for the drugs discussed in the following sections.

TABLE 28.2

Categories of Fetal Risk Factors Assigned to All Medications

| Category A | Controlled studies in humans fail to show a risk to the fetus in the first trimester |

| Category B | Animal studies have not demonstrated a fetal risk, but controlled studies have not been performed in humans, or animal studies have shown adverse effects but those have not been confirmed in controlled human studies |

| Category C | Animal studies have shown adverse effects and no controlled human studies have been performed, or studies in animals and humans have not been performed |

| Category D | There is positive evidence of human fetal risk, but the benefits from use in pregnant women may be acceptable despite the risk |

| Category X | The drug is contraindicated based on its demonstrated capacity to cause fetal abnormalities |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree