LIMP

SUSANNE KOST, MD, FAAP, FACEP AND AMY D. THOMPSON, MD, FAAP, FACEP

Limping is a common complaint in the pediatric acute care setting. A limp is defined as an alteration in the normal walking pattern for the child’s age. The average child begins to walk between 12 and 18 months of age with a broad-based gait, gradually maturing into a normal (adult) gait pattern by the age of 3 years. A normal gait cycle can be divided into two phases: Stance and swing. The stance phase, the time from the heel striking the ground to the toe leaving the ground, encompasses about 60% of the gait cycle. The swing phase involves a sequence of hip then knee flexion, followed by foot dorsiflexion and knee extension as the heel strikes the ground to begin the next cycle.

The causes of limping are numerous, ranging from trivial to life-threatening, but most children who limp do so as a result of pain, weakness, or deformity. Pain results in an antalgic gait pattern with a shortened stance phase. The most common causes of a painful limp are trauma and infection. Neuromuscular disease may cause either spasticity (e.g., toe-walking) or weakness, which results in a steppage gait to compensate for weak ankle dorsiflexion. Ataxia may be interpreted by parents as a limp. A Trendelenburg gait is characterized by the torso swinging back and forth to compensate for a pelvic tilt due to weak hip abductors or hip deformities. A vaulting gait may be seen in children with limb-length discrepancy or abnormal knee mobility. A stooped, shuffling gait is common in patients with pelvic or lower abdominal pain.

The evaluation of a child with a limp demands a thorough history and physical examination. A detailed history of the circumstances surrounding the limp should be obtained, with focus on the issues of trauma, pain, and associated fever or systemic illness. The physical examination must be complete because limping may originate from abnormalities in any portion of the lower extremity, nervous system, abdomen, or genitourinary tract. The location of the pain may not represent the source of the pathology, for example, hip pain may be referred to the knee area. Laboratory and imaging studies should be tailored to the findings in the history and physical examination, keeping in mind an appropriate age-based differential diagnosis.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

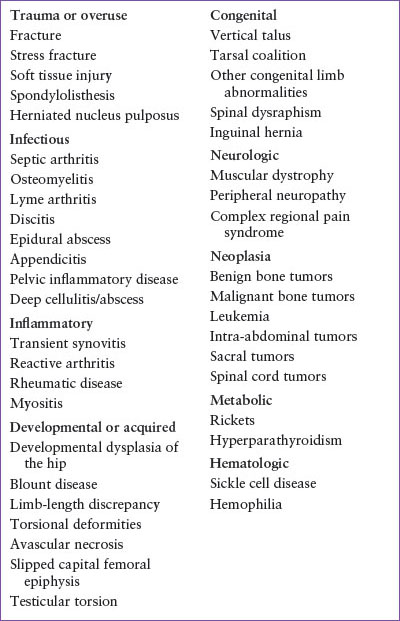

The extensive differential diagnosis of the child with a limp may be approached from several angles: Disease category, location of pathology, or age of the child. Table 41.1 presents the differential diagnosis by disease category; Table 41.2 organizes the differential diagnosis by age and the location of pathology. This section reviews the differential diagnosis within the framework of an algorithmic approach (Fig. 41.1).

The most common cause of limping in all ages is trauma, either acute or repetitive microtrauma (stress fractures). Older children who limp as a result of trauma can generally describe the mechanism of injury and localize pain well. The toddler and preschool age groups, with their limited verbal ability and cooperation skills, often provide a diagnostic challenge. A common type of injury in this population (often not witnessed) is the aptly named “toddler’s fracture,” a nondisplaced spiral fracture of the tibial shaft that occurs as a result of torsion of the foot relative to the tibia. Occult fractures of the bones in the foot also occur in young children. Initial plain radiographic findings may be subtle, or at times nonexistent, but will become apparent in 1 to 2 weeks. Another fracture often lacking initial radiographic confirmation is a Salter–Harris type I fracture, which presents as tenderness over a physis after trauma to a joint area. Stress fractures may also lack overt radiographic findings. Common sites for overuse injury include the tibial tubercle (Osgood–Schlatter disease), the anterior tibia (shin splints), and the calcaneus at the insertion of the Achilles tendon (Sever disease). More information on the subject of fractures is found in Chapter 119 Musculoskeletal Trauma.

Trauma may also induce limping as a result of soft tissue injury. Although young children are more likely to sustain fractures than sprains and strains, the latter can occur. Joint swelling and pain out of proportion to the history of injury raises the possibility of a hemarthrosis as the initial presentation of a bleeding disorder (see Chapter 101 Hematologic Emergencies). Severe soft tissue pain and swelling in the setting of a contusion or crush injury suggests possible compartment syndrome. With compartment syndrome, pain is exacerbated by passive extension of the affected part; pallor and pulselessness are late findings. Severe pain of an entire limb out of proportion to the history of injury suggests complex regional pain syndrome. This entity is most common in young adolescent girls. It may be accompanied by mottling and coolness of the extremity, presumably as a result of abnormalities in the peripheral sympathetic nervous system.

A limp that is accompanied by a history of fever or recent systemic illness is likely to be infectious or inflammatory in origin. However, the absence of fever does not preclude the possibility of a bacterial bone or joint infection, and many infections are preceded by a history of minor trauma. Septic arthritis is the most serious infectious cause of joint pain and limp. It is more common in younger children and typically presents with a warm, swollen joint (although swelling in the hip is very difficult to detect clinically). Exquisite pain with attempts to flex or extend the joint is characteristic of septic arthritis, and the degree of pain with motion serves as a helpful clinical sign in distinguishing bacterial joint infection from inflammatory conditions. A common diagnostic challenge is differentiating septic arthritis from transient (or toxic) synovitis in a young child with fever, limp, and pain localized to the hip. Transient synovitis, a postinfectious reactive arthritis, follows a milder course. It is usually preceded by a recent viral respiratory or gastrointestinal illness. Acute-phase reactants may be elevated in both conditions, although usually less so in synovitis. A unilateral joint effusion, which is better visualized with ultrasound than plain films, may be present in both. Bilateral effusions are more suggestive of an inflammatory synovitis. Joint aspiration may be required for a definitive diagnosis because a septic hip is a surgical emergency requiring open drainage. Osteomyelitis is another potentially serious infectious cause of limp, although the presentation is typically more chronic than that of a septic joint. Osteomyelitis, which is also more common in younger children, presents with pain and occasionally warmth and swelling, usually over the metaphysis of a long bone. A reactive joint effusion may be present. Occasionally, osteomyelitis and septic arthritis will coexist. More detailed discussions of both septic joint and osteomyelitis are found in Chapters 102 Infectious Disease Emergencies and 129 Musculoskeletal Emergencies.

TABLE 41.1

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF LIMP BY DISEASE CATEGORY

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree