INTRODUCTION

ANATOMY

In the foot, the plantar epidermis and dermis are thick, except in the arch area. This thick skin is able to withstand the force produced by a moving body but is also quite sensitive to two-point discrimination and pressure. The heel has an 18-mm-thick modified pad of fat separated into chambers by fibrous septae. There is an additional broad internal fibrous arch, called the inner cup ligament, which helps maintain the shape of the heel. The skin of the sole readily hypertrophies and can become quite thickened, especially in people who walk barefoot. The dense fibrous fatty tissue of the ball of the foot and heel makes wound exploration and visualization difficult in the ED.

In contrast to the protective plantar surface, skin on the dorsal aspect of the foot and the entire ankle provides little protection for underlying tendons, nerves, and blood vessels. The dorsum of the foot, the ankle, and the pretibial surface are particularly vulnerable to blunt-force injuries. Most lacerations on the dorsal foot and in the ankle area are easily explored, except for posterior ankle lacerations, a limitation when partial laceration of the Achilles tendon is considered. Lacerations involving the shin, calf, and thigh usually present few problems regarding wound exploration and visualization.

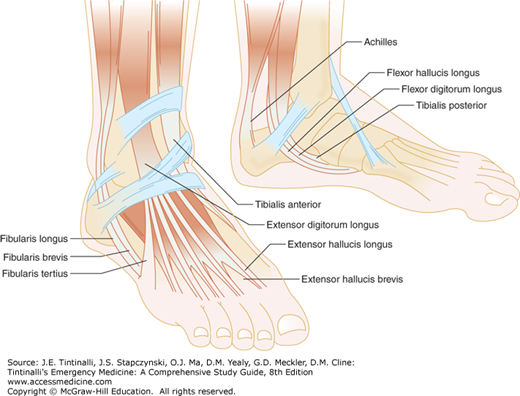

Several important tendons in the leg are at risk for injury. The fibularis longus and fibularis brevis (also known as the peroneus longus and peroneus brevis) tendons, which contribute to foot plantar flexion and eversion, run behind the lateral malleolus and can be lacerated at this location (Figure 44-1). The extensor hallucis longus tendon, which extends the first toe, runs along the top of the first metatarsal and may be injured when heavy objects are dropped on the foot. The Achilles tendon, the primary contributor to foot plantar flexion, may be severed by penetrating injuries to the posterior ankle. Lacerations of the shin rarely involve vital nerves or tendons. Infrapatellar lacerations can transect the patellar tendon, resulting in inability to extend the leg. Suprapatellar lacerations may involve the quadriceps tendon, also resulting in impaired knee extension.

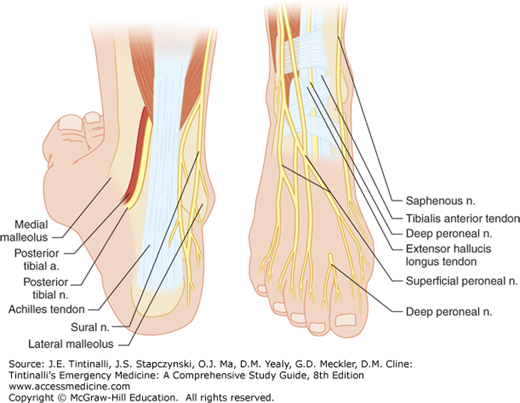

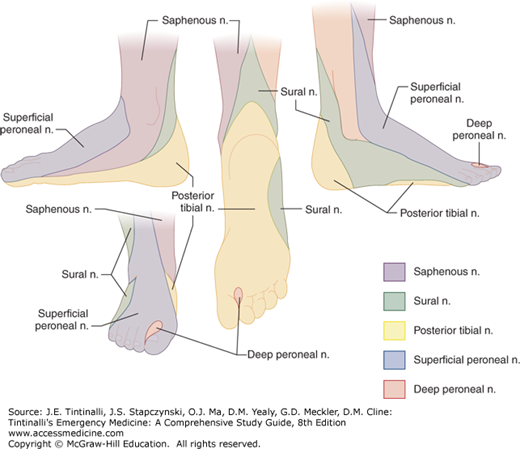

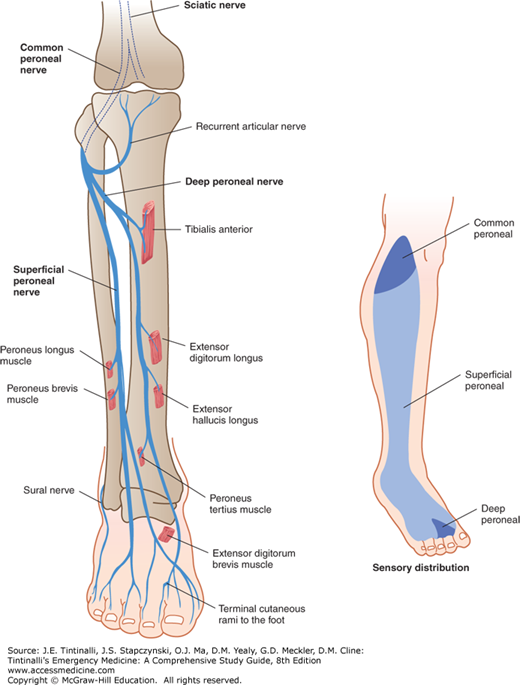

Sensory nerves predominate in the foot, with most motor control of the foot being performed by nerves and muscles in the lower leg (Figures 44-2 and 44-3). The exceptions to this generalization are that the posterior tibial nerve innervates the intrinsic foot musculature, and the deep peroneal nerve innervates the extensor digitorum brevis and extensor hallucis brevis muscles; injuries to these nerves may result in toe clawing.14 The common peroneal nerve can be injured in complex fractures, sharp injuries, or lacerations of the lower extremity resulting in foot drop (Figure 44-4).15

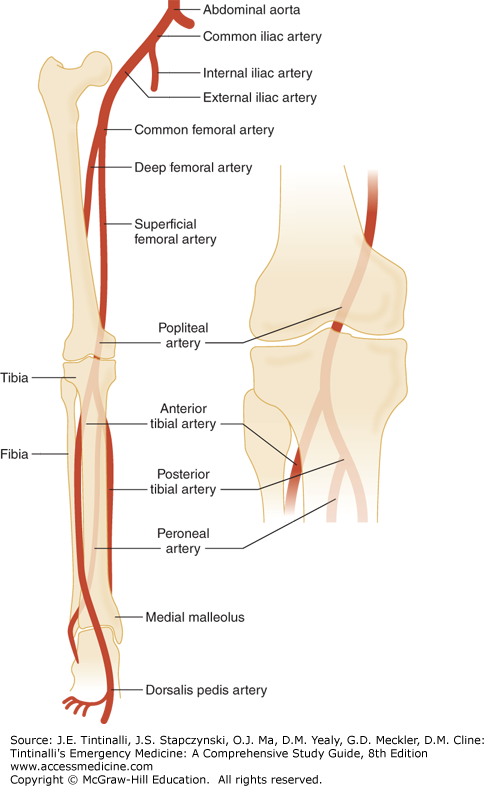

Arterial injury resulting from penetrating and blast wounds most commonly affects the superficial femoral, popliteal, crural, common femoral, and deep femoral arteries (Figure 44-5).16 Arterial injuries are at high risk for limb loss.17

ASSESSMENT

Obtain a description of the mechanism of injury, assessing the potential for damage to underlying tissue, the risk of a retained foreign body, and degree of potential contamination. Determine the time interval from injury to evaluation, because delayed presentations can increase the incidence of infection. Inquire about foreign body sensation, paresthesias, anesthesia, weakness, or loss of function suggesting a nerve, vascular, or tendon injury.

The patient’s age influences wound healing and functional status following the injury. Ask about tetanus immunization status and conditions that increase the risk for infection or delayed wound healing such as diabetes, immunosuppression, or vascular disease. Note the social history, because patients who smoke, consume alcohol, or use illicit substances may be at additional risk of poor healing secondary to vascular disease.

Inspect the wound, noting its location and proximity to underlying nerves or arteries. General appearance, obvious injuries, or visible foreign bodies should be noted; more detailed wound exploration typically waits until after anesthesia and radiographs, if needed. If a nerve laceration is suspected, light touch and/or static two-point discrimination should be tested in the foot and toes and compared with the uninjured side. Two-point discrimination varies in the foot, with normal values of 1.5 cm in the hind, mid, and forefoot, and <1 cm in the big toe, but these measures are not reliable in patients with diabetes or peripheral vascular disease.18 Sensory deficits to the foot can result in significant long-term morbidity. Motor function may be easier to assess after anesthesia or reduction of an associated fracture or dislocation. Obtain prompt surgical consultation if motor nerve or major sensory nerve injury is identified because primary repair may be indicated.14 Nerve injuries caused by open blunt injuries are not typically repaired at the time of injury, in part because of the risk of infection and in part because of the possibility that a contused nerve will regain function without surgical intervention.

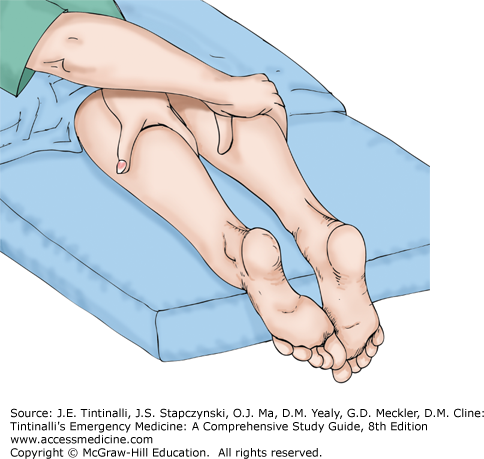

Evaluate for tendon injuries by assessing motor function, palpating the tendon, and observing the tendon through its entire range of motion. A partially injured tendon may be noted to “catch” on the synovial sheath during range of motion. Lacerations of the Achilles tendon may be easily visualized with simple exploration through the open wound, by palpating a defect in the tendon, or by US. Sometimes, the tendon laceration may not be visible or palpable, and presence of active plantar flexion of the foot cannot be used to exclude the injury. The Achilles tendon is not the only structure responsible for plantar flexion of the foot—the tibialis posterior muscle flexes the foot at the ankle. The Thompson test can assist in detecting an Achilles tendon rupture. The patient lies prone on the examination cart with the feet hanging over the edge of the bed, and the examiner places one hand on each mid-calf (Figure 44-6). If the Achilles tendon is intact, the foot plantar flexes when the calf is squeezed, and comparison with the unaffected side is helpful to detect subtle movement. A positive Thompson test is when the affected foot does not flex, indicative of an Achilles tendon rupture.19

Document the location, length, estimated depth, and general shape of the wound. Provide anesthesia, cleanse the wound, and carefully inspect the full extent of the wound for foreign bodies. The loose, thin skin over the dorsum of the foot allows for adequate visual, digital, and instrument exploration for tendon lacerations, as well as for foreign body discovery. The dense tissue of the plantar surface of the foot limits wound visualization, and the risk of creating further injury limits exploration. An exception to this general rule of limited exploration on the weight-bearing plantar surface is in an infected wound with suspected foreign body. With significant injury to the leg, like a crush injury, consider compartment syndrome and evaluate accordingly.

ANCILLARY STUDIES

Obtain radiographs when a fracture, radiopaque foreign body, or joint penetration is suspected.20,21 Foregoing radiographs and using wound exploration alone to exclude a foreign body is a reasonable approach, but carries a small risk of missing a retained object.22,23,24 CT or MRI can detect retained organic material. Bedside US may identify retained foreign bodies and detect tendon lacerations and fractures (see chapter 45, “Soft Tissue Foreign Bodies”). Fluoroscopy is a useful dynamic imaging modality that may assist in identifying and removing foreign bodies. No single imaging modality or wound exploration will identify every foreign body; emphasize close follow-up if the mechanism of injury suggests a potential for a foreign body but none was identified on imaging or wound exploration.

Lacerations in proximity to joint spaces may penetrate the articular space. Detecting joint penetration by physical examination alone is often difficult. Intra-articular gas on plain radiograph is a sign of joint penetration. If the radiograph does not display intra-articular gas, use the saline load test to determine joint integrity, especially in the knee and ankle.25,26 Inject sufficient amounts of saline to adequately stress the capsule, because false-negative results may be obtained if too little fluid is injected.27,28 Volumes injected into the knee may vary based on the location of the approach; mean volumes of injected fluid needed for a positive result are approximately 65 mL and 95 mL, respectively, at the inferomedial and superomedial locations.26,27,28 Fluid leaking from the wound indicates joint penetration. Do not add methylene blue to the injected saline to aid in visualization of fluid existing in the wound because it does not increase diagnostic accuracy compared to saline alone and the resultant staining of the articular surfaces may affect operative management of intra-articular injuries.29

TREATMENT

Anesthesia can be administered by topical, local, or regional routes. The toes can be anesthetized using standard digital blocks. Epinephrine-containing local anesthetics can be safely used for digital blocks in toes (see chapter 36, “Local and Regional Anesthesia”).

Lacerations to the dorsum of the foot can be sufficiently anesthetized by infiltration of local anesthetic. The plantar surface of the foot is sensitive to the infiltration of a local anesthetic, so regional nerve blocks may be helpful. The sural nerve block and the posterior tibial nerve block (see chapter 36) are the two most commonly used nerve blocks for the foot. Topical local anesthetic preparations can achieve adequate anesthesia on the dorsum of the foot and leg, but may be ineffective on the dense epidermis of the plantar surface of the foot. In children, distraction techniques, use of child-life specialists, anxiolytics, and conscious sedation may help alleviate anxiety and pain response (see chapter 113, “Pain Management and Procedural Sedation in Infants and Children”).

Wound irrigation with copious amounts of saline is recommended due to the increased risk of infection with lower extremity lacerations (see chapter 40, “Wound Preparation”).30,31

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree