INTRODUCTION

Many mechanisms provoke acute joint symptoms: degradation and degeneration of articular cartilage (osteoarthritis), deposition of immune complexes or immune system–related phenomena (rheumatoid arthritis, rheumatic fever and possibly, a component of gonococcal arthritis), crystal-induced inflammation (gout and pseudogout), seronegative spondyloarthropathies (ankylosing spondylitis [see chapter 282, “Systemic Rheumatic Diseases”] and reactive arthritis [postinfectious with HLA-B27 susceptibility]), and bacterial invasion (gonococcal and nongonococcal septic arthritis, including Lyme arthritis) or viral invasion (viral arthritis). These processes impact joint capsules and surfaces, resulting in a cascade of reactive and inflammatory events. Septic arthritis is invasion of a joint by an infectious agent with organism proliferation and associated inflammation; bacterial arthritis is a subset of septic arthritis. Under ideal conditions, the infectious agent is recoverable from the joint fluid in septic arthritis, but in clinical practice, this is often not the case. This chapter reviews the common causes and treatments of acute nontraumatic joint pain. Joint injuries are discussed in section 22, “Injuries to Bones and Joints,” and disorders due to repetitive use syndromes are discussed in section 23, “Musculoskeletal Disorders,” by anatomic site.

CLINICAL APPROACH TO ACUTE JOINT PAIN

Septic arthritis is the most important consideration in the evaluation of a swollen, warm, and painful joint. Urgent treatment may prevent both joint destruction and mortality (11% with treatment).1,2 The diagnosis of septic arthritis is clinical and is supported by diagnostic tests.1,2 No single diagnostic parameter is sufficiently sensitive to screen patients for septic arthritis including synovial WBC counts.3

Risk factors (Table 284-1),3,4 the number of joints involved (Table 284-2), and the migratory pattern (Table 284-3), if one exists, aid in the differential diagnosis. Approximately 85% of patients with nongonococcal septic arthritis present with a single joint infected; Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae are more likely to infect two or more joints simultaniously.5,6,7,8 Septic arthritis involving more than one joint can occur in rheumatoid arthritis (50%), immunocompromise, gout, diabetes, and/or renal disease; the morality rate is significantly higher in patients with polyarticular septic arthritis (11% vs 30%).5,7 Recent joint surgery and cellulitis overlying a prosthetic hip or knee are the only findings on history or physical examination that significantly alter (both increase) the probability of nongonococcal septic arthritis.3

| Nongonococcal | Gonococcal |

|---|---|

| Injection drug use* | HIV infection* |

| Diabetes mellitus* | Injection drug use* |

| Rheumatoid arthritis* | Pregnancy |

| Prosthetic joint, knee,* or hip* | Menses |

| Immunosuppression, HIV* | Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| Age: >80 y old* | Complement deficiency |

| Skin ulceration and/or infection* | |

| Hemophilia | |

| Hypogammaglobulinemia | |

| Malignancy | |

| Hemodialysis | |

| Liver disease | |

| Alcoholism | |

| Steroid therapy |

| Number of Joints | Differential Considerations for Typical Presentations |

|---|---|

| 1 = Monoarthritis | 85% of nongonococcal septic arthritis* Crystal-induced (gout, pseudogout) Gonococcal septic arthritis Trauma-induced arthritis Osteoarthritis (acute) Lyme disease Avascular necrosis Tumor |

| 2–3 = Oligoarthritis† | 15% of nongonococcal septic arthritis, more common with Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae Lyme disease Reactive arthritis (Reiter’s syndrome) Gonococcal arthritis Rheumatic fever |

| >3 = Polyarthritis† | Rheumatoid arthritis Systemic lupus erythematosus Viral arthritis Osteoarthritis (chronic) Serum sickness Serum sickness–like reactions |

When septic arthritis is suspected, aspirate joint fluid, and obtain analysis and culture of the aspirate to direct treatment.1,2 Table 284-4 provides diagnostic guidance based on synovial fluid results in the context of different patient characteristics.1–12

| Key Factor | Patient Status | Joint Aspiration | Diagnostic Considerations/Management |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Gram stain | Acute joint pain and swelling | Gram stain positive for bacteria | Initiate empiric IV antibiotics, admit to the hospital, monitor culture and patient course (positive Gram stain is found in <50% of patients with septic arthritis). |

| Classic synovial WBC count | Acute joint pain and swelling | >50,000 WBC/mm3 or >90% PMNs | Synovial fluid with >50,000 WBC/mm3 is 56% sensitive and 90% specific for septic arthritis. Initiate empiric IV antibiotics and hospital admission. |

| Increased sensitivity of lower synovial WBC counts | Acute joint pain and swelling in a patient with risk factors for septic arthritis or systemic signs of infection | >25,000 WBC/mm3 or >90% PMNs | Synovial fluid with >25,000 WBC/mm3 is 73% sensitive and 77% specific for septic arthritis. Consider empiric IV antibiotics and admission to the hospital for monitoring of patient course and cultures. |

| Acute gout with coexisting septic arthritis | Acute joint pain and swelling; patient with acute gout or history of gout with systemic signs of infection | Crystals, >2000 WBC/mm3, or >90% PMNs | Crystal-induced arthritis may coexist with septic arthritis; cell counts are <6000 WBC/mm3 in 10% of infected joints; more than one joint is involved in 10%–45%. Look for infected tophi. Consider empiric IV antibiotics and admission to the hospital for monitoring of patient course and cultures. |

| Prosthetic joint | Acute pain and swelling in patient with prosthetic joint | >10,000 WBC/mm3, >90% PMNs | Consult operating orthopedic surgeon before aspiration if possible. AAOS definition for acute periprosthetic infection is 3 of the following: (1) CRP elevated above 100 milligrams/L and ESR elevated above local norm, (2) synovial WBC >10,000/mm3, (3) synovial PMNs >90%, (4) positive culture, and (5) positive histologic analysis of periprosthetic tissue. |

| Immunocompromise | Joint swelling in an immunocompromised patient or systemic signs of infection in a patient with immunocompromise | >200 WBC/mm3, >25% PMNs | Immunocompromised patients sustain septic arthritis with diminished immune response; cell counts and percent PMNs are frequently lower than in immunocompetent patients with similar infections. Consider empiric IV antibiotics and admission to the hospital for monitoring of patient course and cultures. |

| Gonococcal arthritis | Monoarticular or polyarticular joint pain in a patient with history of unprotected sex (primarily in young patients) | 10,000–80,000 WBC/mm3 | Positive culture in <50% of infected joints; collect urogenital cultures plus pharynx and rectum cultures as determined by history. Consider empiric IV antibiotics and admission to the hospital for monitoring of patient course and cultures. |

| Rheumatoid arthritis with coexisting septic arthritis | Joint pain and/or swelling in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis | 2000–120,000 WBC/mm3 | Severe pain and limited range of motion may be absent in patients on immunosuppression. Look for infected rheumatoid nodules or ulcerated foot calluses; source in 76% of cases. Consider empiric IV antibiotics and admission to the hospital for monitoring of patient course and cultures. |

| Lyme disease | Acute joint pain in a patient living in a Lyme disease–endemic area or with a history of rash or tick bite | 200–300,000 WBC/mm3 | Consider empiric antibiotics and close follow-up to monitor culture and patient course; admit if clinical picture is indistinguishable from septic arthritis. Arthralgia appears months after initial symptoms. Joint effusion (moderate to large) may be out of proportion to the patient’s pain (mild to moderate). Knee is the most common affected joint. |

| Post trauma | Joint trauma several days prior, initial swelling, now increasing pain | 0–2000 WBC/mm3, <25% PMNs, 0–500 RBC/mm3 | Posttraumatic effusions may become infected in patients with skin infections or bacteremia. Aspiration of the joint reduces pain for approximately 1 week, but has no effect on long-term disability. |

| Dry tap | Patient with acute joint pain and suspected swelling, with or without other symptoms or signs to suggest septic arthritis | “Dry tap” | Major causes of dry tap are mistaken physical diagnosis of effusion; blockage of the needle by plica, fat, or debris; or synovial fluid with high viscosity or true lipoma arborescens (benign replacement of subsynovial tissue by fat cells). Use US to determine true effusion and direct needle to largest collection of fluid. |

| Normal synovial cell counts | Patient with sufficient joint pain and swelling to warrant arthrocentesis, no comorbidities, absent signs and symptoms of sepsis | <200 WBC/mm3, <25% PMNs | Normal WBC cell counts and differential percentages make the diagnosis of septic arthritis unlikely in a patient without comorbidities or objective signs of infection. A mechanism should be in place for timely follow-up of culture results if they turn positive. |

Analyze joint fluid for Gram stain, leukocyte count with differential, and a wet preparation for crystals.4,6 Glucose, protein, and lactate dehydrogenase levels do not direct treatment decisions.4 Synovial lactate levels may prove an aide in identifying septic arthritis if future studies confirm preliminary reports.3 Culture for gonococci and anaerobes, in addition to typical gram-positive and -negative organisms.1,2,4

Serum erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein levels are commonly elevated in several acute inflammatory and reactive arthritides (gonococcal and nongonococcal septic arthritis, crystal-induced, spondyloarthropathies, and rheumatoid and Lyme arthritis) but are not helpful for establishing a specific diagnosis in adults. However, erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein are recommended as an aid to monitor response to therapy by the British Society of Rheumatology Guidelines,2 and the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons guidelines include erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein as part of their minor criteria for the diagnosis of acute periprosthetic joint infection (Table 284-4).11 The American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons also recommends that an elevation of either erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein be used as criterion to aspirate a painful prosthetic joint with increased warmth.11 The sensitivity of the serum WBC count in adults for the diagnosis of nongonococcal bacterial septic arthritis is approximately 60%.3 Blood cultures should be obtained before antibiotic therapy for presumptive or possible septic arthritis. However, the sensitivity for identifying the causative organism in adults and children with nongonococcal bacterial septic arthritis is 23% to 36%.3 Elevated procalcitonin levels provide 90% specificity to help rule in the diagnosis of septic arthritis but are only 67% sensitive in screening for the diagnosis.3,13

Laboratory studies can aid in the diagnosis at follow-up. Possible studies include Lyme titer, rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, HLA-B27 tissue typing, lupus anticoagulant, and repeat synovial fluid analysis.

Bedside US is useful to identify joint effusion and aids successful joint aspiration.14,15 Obtain radiographs of an inflamed joint if trauma, tumor, avascular necrosis, and osteomyelitis are diagnostic considerations. Radioisotope scanning is not usually required for ED diagnosis but can be useful to detect osteomyelitis, occult fracture, avascular necrosis, or tumor. MRI is not recommended for routing assessment of septic arthritis but may be helpful for difficult diagnostic cases. MRI is more sensitive to identify joint effusion than specific for the diagnosis of septic arthritis.16

ARTHROCENTESIS

Prepare the site to avoid bacterial contamination. The skin overlying the affected joint should be free of cellulitis or impetigo to avoid contamination of the joint space during arthrocentesis. Orthopedics should be consulted before aspiration of a prosthetic joint for direction in diagnostic workup and interpretation of results.11 Other relative contraindications to joint aspiration are coagulopathy, including hemarthrosis in hemophiliac patients before factor replacement.17

Cleanse a large area overlying and adjacent to the affected joint with povidone-iodine solution. After air drying, clean the skin with an alcohol wipe to remove the povidone-iodine solution from the skin surface. Removal of the overlying povidone-iodine prevents the introduction of the povidone-iodine antiseptic into the joint, which can result in chemical irritation or sterilization of the aspiration sample. Next place sterile drapes over the site and maintain sterile technique throughout the procedure.

Anesthetize the skin and soft tissues overlying the joint with a 25- to 30-gauge needle. Avoid intra-articular injection of anesthetic because the anesthetic can inhibit bacterial growth and may result in a spuriously negative culture in an early septic joint.

Use a large-bore needle (18 or 19 gauge) for aspiration of fluid from large joints. Use smaller-bore needles for small joints (no smaller than 22 gauge). Choose a syringe large enough to accommodate the anticipated volume of fluid within the joint space. Remove as much synovial fluid as possible to obtain a good diagnostic sample and to relieve pain from joint capsule distention. Promptly send aspirated fluid to the laboratory for culture, Gram stain, leukocyte count with differential, and crystal analysis. US should be used in the event of a dry tap (see Table 284-4).

US can facilitate shoulder aspiration. The anterior or posterior approach can be used.

Have the patient sit upright, facing you, and externally rotate the humerus. Insert the needle just lateral to the coracoid process, between the coracoid process and the humeral head (Figure 284-1A). Direct the needle posteriorly. If it is difficult to locate the coracoid process, the posterior approach to the glenohumeral joint may be easier.

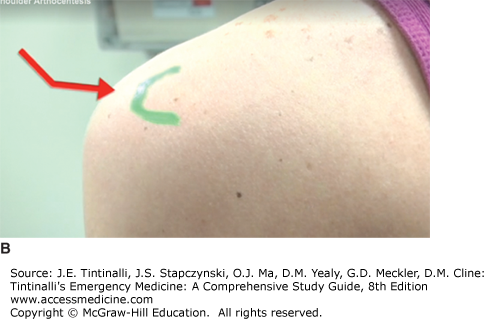

Sit the patient upright with the back facing you. Palpate the spine of the scapula to its lateral limit: the acromion. Identify the posterolateral corner of the acromion. Use a 1.5-inch needle. The point for needle insertion is 1 cm inferior and 1 cm medial to the posterolateral corner of the acromion (Figures 284-1B and 284-2). Direct the needle anterior and medial toward the presumed position of the coracoid process. The glenohumeral joint is located at a depth of approximately 1.0 to 1.5 inches.

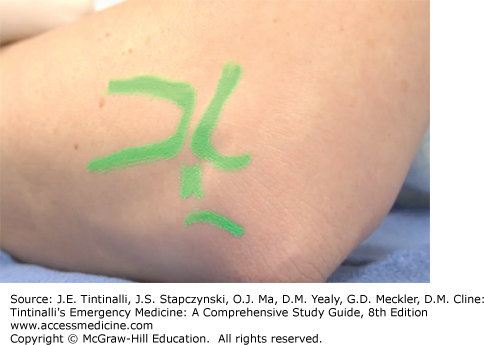

Use a lateral or posterior approach to the elbow joint. Do not use a medial approach to avoid neurovascular structures. Place the elbow in 90-degree flexion, resting on a table, with the hand prone to widen the joint space. Locate the radial head, lateral epicondyle of the distal humerus, and the lateral aspect of the olecranon tip. These three landmarks form the anconeus triangle. The center of this triangle is the site for needle entry into the skin. Using the tip of the gloved index finger of the nondominant hand, palpate a sulcus just proximal to the radial head. The sulcus is the needle entry point. Direct the needle medial and perpendicular to the radius toward the distal end of the antecubital fossa (Figure 284-3).

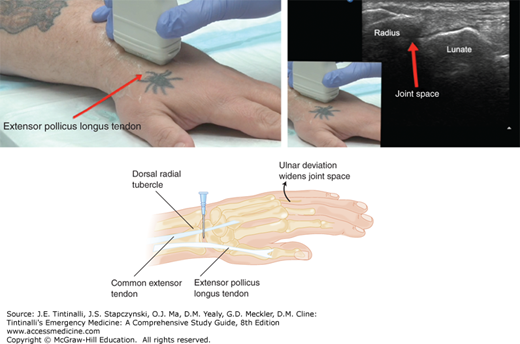

Landmarks for wrist arthrocentesis are palpable with the wrist in a neutral position. The landmarks are the radial tubercle of the distal radius, the anatomic snuffbox, the extensor pollicis longus tendon, and the common extensor tendon of the index finger (Figure 284-4). Insert the needle perpendicular to the skin, ulnar to the radial tubercle and the anatomic snuffbox, between the extensor pollicis longus (just ulnar to the extensor pollicis longus) and the common extensor tendons.

Hip arthrocentesis may be performed by an anterior or medial approach. If local practice dictates open surgical assessment and drainage, an orthopedic consultant will often perform this procedure. US-guided arthrocentesis by an emergency physician or radiologist is also accepTable if local practices and training are in place to support this approach (Figure 284-5). Controversy exists regarding the utility of US or MRI as a screening test before open surgical evaluation.15,18 Immediate consultation with an orthopedic surgeon is therefore desirable when a diagnosis of septic hip arthritis is considered.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree