JAUNDICE: CONJUGATED HYPERBILIRUBINEMIA

ERIN B. HENKEL, MD AND SANJIV HARPAVAT, MD, PhD

INTRODUCTION

The pediatric emergency provider is typically confronted with the finding of hyperbilirubinemia in one of two situations: (1) a jaundiced child, or (2) an incidental finding during a laboratory evaluation. When conjugated hyperbilirubinemia is found, the challenge lies in determining if it is a sign of a life-threatening condition.

NORMAL BILIRUBIN PHYSIOLOGY

Senescent red blood cells release heme which is eventually converted to unconjugated bilirubin. Unconjugated bilirubin then binds to albumin and is transported to the liver. In the liver sinusoids, unconjugated bilirubin detaches from albumin and gains entry into the hepatocyte, where it is conjugated with glucuronide by the action of uridine diphosphate glucuronyl transferase. The soluble conjugated diglucuronide then is secreted out of the hepatocyte, across its canalicular membrane into the bile. Conjugated bilirubin, along with bile salts, phospholipids, cholesterol, and metabolites are the major constituents of bile. Bile flows through the intrahepatic biliary tree, into the extrahepatic bile ducts (including the common bile duct), and finally into the intestine at the ampulla of Vater. In the intestine, bacterial flora converts bilirubin to urobilinogen. Some urobilinogen is reabsorbed and taken up by the liver cells, only to be reexcreted into the bile. A small percentage of urobilinogen escapes into the systemic circulation and is excreted in the urine. The unabsorbed urobilinogen is excreted in the stool as fecal urobilinogen (see Chapter 40 Jaundice: Unconjugated Hyperbilirubinemia).

DEFINITION

The definition of conjugated hyperbilirubinemia is controversial. Some commonly used definitions are a conjugated bilirubin level higher than 2 mg/dL or a conjugated bilirubin that is more than 20% of the total bilirubin. Since these definitions are broad and frequently used in the absence of additional considerations, one risks missing significant liver diseases. A more sensitive definition is any conjugated bilirubin level above the laboratory’s normal reference interval. Laboratory reference intervals are calculated using the 2.5th to 97.5th percentile of values in a population, that is, the middle 95% of values. This definition is very sensitive but less specific for liver disease. From the perspective of an emergency physician, following this definition will decrease the risk of missing diagnoses.

ETIOLOGIES

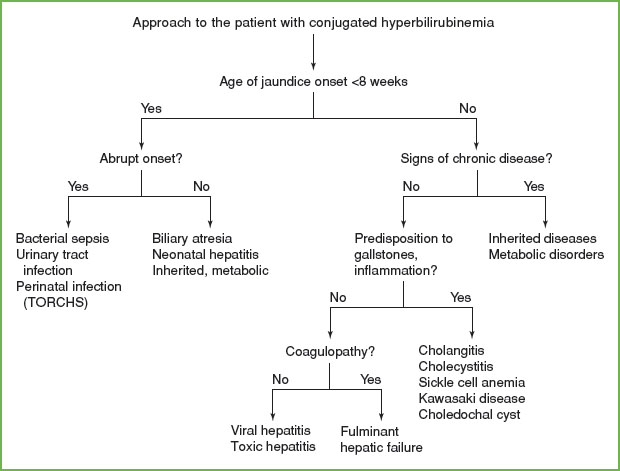

Once an elevated conjugated bilirubin value has been identified, the next step is to consider the causes that explain the finding. A systematic approach to making the diagnosis is helpful (Fig. 39.1). Conceptually, conjugated hyperbilirubinemia occurs for four reasons: Elevation from increased bilirubin production, hepatocyte injury, bilirubin transporter defects, or obstruction.

Increased bilirubin production: When there is bilirubin overproduction, the abundance of unconjugated bilirubin must be converted to conjugated bilirubin in order for it to be excreted. As a result, conjugated bilirubin levels can rise. In newborns, red blood cell lysis, ABO incompatibility, G6PD, and cephalohematoma can all cause an abundance of unconjugated and subsequently conjugated bilirubin.

Increased bilirubin production: When there is bilirubin overproduction, the abundance of unconjugated bilirubin must be converted to conjugated bilirubin in order for it to be excreted. As a result, conjugated bilirubin levels can rise. In newborns, red blood cell lysis, ABO incompatibility, G6PD, and cephalohematoma can all cause an abundance of unconjugated and subsequently conjugated bilirubin.

Hepatocyte injury: Hepatocyte injury from any mechanism will cause the breakdown of the liver cell, which results in the release of conjugated bilirubin into the bloodstream. This occurs with liver failure, toxic injury, infections, and metabolic disorders.

Hepatocyte injury: Hepatocyte injury from any mechanism will cause the breakdown of the liver cell, which results in the release of conjugated bilirubin into the bloodstream. This occurs with liver failure, toxic injury, infections, and metabolic disorders.

Bilirubin transporter defects: Transporter defects can be acquired in the setting of general liver injury. They can also be isolated, causing only conjugated hyperbilirubinemia without associated liver damage. In these situations, conjugated bilirubin is retained in the liver which can discolor the liver but does not cause direct toxicity. Other components of bile, such as toxic bile acids and metabolites, flow normally out of the liver and into the intestine. Dubin–Johnson syndrome is an example of a defect in conjugated bilirubin transporters.

Bilirubin transporter defects: Transporter defects can be acquired in the setting of general liver injury. They can also be isolated, causing only conjugated hyperbilirubinemia without associated liver damage. In these situations, conjugated bilirubin is retained in the liver which can discolor the liver but does not cause direct toxicity. Other components of bile, such as toxic bile acids and metabolites, flow normally out of the liver and into the intestine. Dubin–Johnson syndrome is an example of a defect in conjugated bilirubin transporters.

Obstruction: When the biliary tree becomes obstructed, liver damage results. The classic example is biliary atresia (BA), where bile salts backup into the liver and induce rapid fibrosis, cirrhosis, and eventual liver failure.

Obstruction: When the biliary tree becomes obstructed, liver damage results. The classic example is biliary atresia (BA), where bile salts backup into the liver and induce rapid fibrosis, cirrhosis, and eventual liver failure.

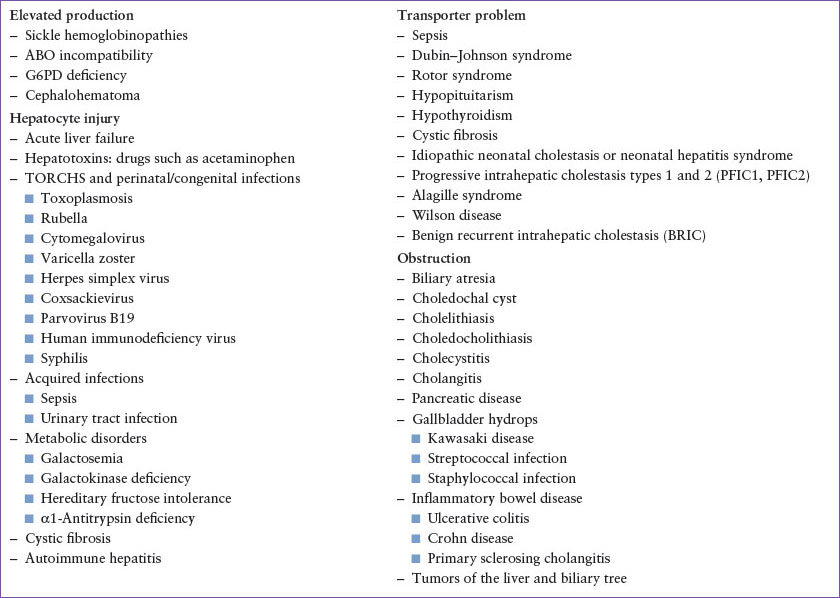

(See Table 39.1.)

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The provider interviewing the patient and family with hyperbilirubinemia can often differentiate the cause and severity of the underlying issue with a thorough medical history and physical examination (Fig. 39.1). The following questions can help elucidate key points in differentiating the cause of conjugated hyperbilirubinemia:

1. Is this the first episode of jaundice? (to distinguish between an acute event or a chronic process)

FIGURE 39.1 Approach to the patient with conjugated hyperbilirubinemia.

TABLE 39.1

CAUSES OF CONJUGATED HYPERBILIRUBINEMIA

2. Are the stools acholic? Is there abdominal pain? If so, does the pain increase with certain foods? (to determine whether biliary obstruction is present)

3. Is fever, fatigue, emesis, or diarrhea present? (to investigate viral causes, including EBV, hepatitis A, and hepatitis B)

4. Are there any rashes, arthralgias, arthritic joints, or conjunctivitis? (to question about autoimmune causes)

5. Have there been any recent behavioral changes, especially in a teenager? (to evaluate for Wilson disease)

6. Is itching, bleeding, bruising, swelling, excessive sleeping, or mental status changes present? (to assess overall liver function)

7. What medications are taken, and are any of them new? (to identify potential hepatotoxins)

8. Is there a family history of liver diseases, early-onset emphysema, or iron overload? (to evaluate for genetic causes, such as Alagille syndrome, α1-antitrypsin disease, or hemochromatosis)

9. (For infants) Were there any infections during pregnancy? Were the newborn screens normal?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree